TB872: Communities and networks

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

As we near the end of Part 1 of the TB872 module, we encounter something which I could write about all day: Communities of Practice (CoP). I’m going to reference some recent writing I’ve done and workshops we’ve run through WAO, partly to help jog my memory, but also to find again easily should I need it for one of my assessments:

- Professional Belonging: Networking through Communities of Practice (23 November 2023)

- The Future of Trust in Professional Networks (25 September 2023)

- Steps to Success when building a Community of Practice (5 October 2022)

There are other ones, which are more adjacent to this which are more focused on Open Recognition, especially Using Open Recognition to Map Real-World Skills and Attributes (Part 1 / Part 2). I’m surprised that those latter two haven’t had more interest and the ideas in them taken up, but I digress.

Before going any further, it’s worth defining what a CoP actually is:

Communities of practice are formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning in a shared domain of human endeavor: a tribe learning to survive, a band of artists seeking new forms of expression, a group of engineers working on similar problems, a clique of pupils defining their identity in the school, a network of surgeons exploring novel techniques, a gathering of first-time managers helping each other cope.

‘Introduction to communities of practice’ (2022), 12 January. Available at: https://www.wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice (Accessed: 25 November 2023).

CoPs all have the following:

- Domain: there has to be a shared identity defined by a commitment to a ‘domain’ of practice. Being a member of the CoP implies some kind of commitment to this domain, as opposed to being a member of a ‘network’. Being part of the domain doesn’t necessarily confer ‘expertise’ but rather what Wenger and Traynor call a “collective competence”.

- Community: somewhat obviously, a CoP has to have members which engage with one another with the domain. They talk with one another, sharing information, helping each other, and (crucially) they actually care about their relationships with one another. Sometimes drawing a boundary around a CoP is difficult, because it’s not based on job title, or visiting the same online forum as someone else; a CoP depends on interaction and learning. Even if the actual practice that people do is solitary (e.g. hiking long-distance trails) there can still be a vibrant CoP around it.

- Practice: the ‘practice’ is what the members of the community actually talk about and help each other with. This goes beyond a community of ‘interest’, as members of a CoP are practitioners. They are not merely people who all like the same things. For example, the Taylor Swift fandom could be a Community of Interest, but if they start actually doing stuff together (e.g. collecting memorabilia, creating a database of performances) then they may start edging into a CoP. The important thing isn’t necessarily that people realise that they’re engaging in a practice within a community in a given domain — I’ve been part of lunchtime discussions in staff rooms as a teacher which could be considered a CoP.

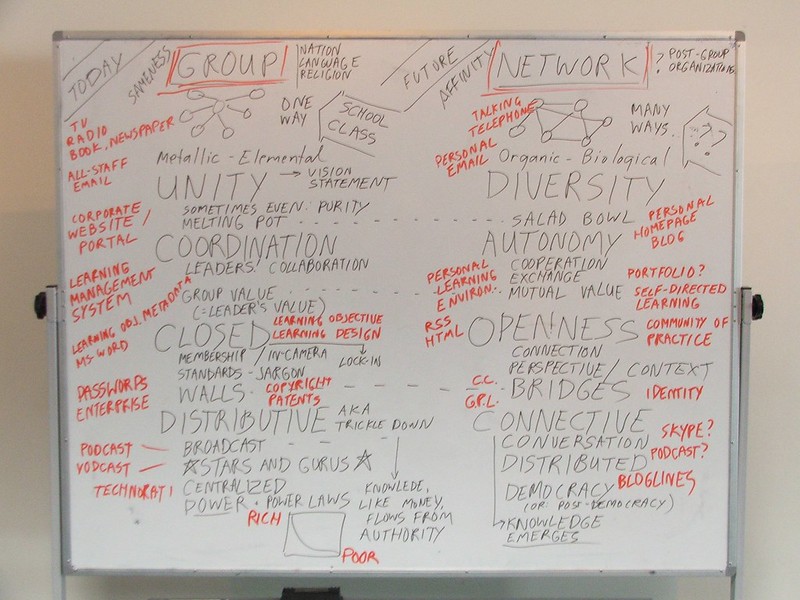

The course materials ask us to reflect on our experiences of being part of communities as opposed to networks. One image that’s stuck with me since 2006 is from Stephen Downes, who drew out the following at a conference in Auckland to illustrate a point he was making:

This was very much the Web 2.0 era, and the very next day he followed up with a post reflecting on the pushback he’d got from some quarters:

It took exactly 24 hours for someone to propose a “middle way” (this is what passes for innovation these days). “Could there be “middle way” or “third way”? Something that would be between the ‘closed groups’ and ‘individuals in open networks’?”

It will soon be noticed that a person can be both an individual (and hence a member of a network) and a member of a group. That they can belong to many networks and many groups. That any number of ‘middle ways’ can be derived from variations on this theme.

[…]

The core of the issue is whether learning in general should be based on groups or networks. Everybody says, ‘learning is social’, and thus (no?) must be conducted in groups. But networks, too, are social. Learning can be social and not conducted in groups. Where to now, social construction?

The reason I share this here, other than the fact that Stephen has been a critical friend to my work for almost two decades, is that one could see the concept of a CoP as a ‘middle way’ between a group and a network. That is to say, there is a boundary, so it is group-ish. But it depends on people interacting with their full identity, rather than being subsumed into the group, and therefore is network-ish.

The assignment that I’m responding to in this post asks me to:

Review your own experiences of communities and networks in relation to your practices and plot them in some way, possibly using a timeline or a spray diagram. Discuss with others, possibly on the module discussion forum, whether and how these groups have been important to you in helping you improve your practices. If networks and communities have not been a significant part of your experience or if you do not consider them important to your practice, consider whether increased involvement and networks is desirable or feasible in relation to your practice.

As I’ve known for 15 years, the way my brain is wired not only means I get migraines, but I also am mildly synaesthetic. In my case, this means that I see time very visually, which, I understand from talking with other people, isn’t “normal”. I see it as a bit of a superpower, being able to zoom into different periods of history. It’s not that I get to choose how to represent it, that’s just how my brain works.

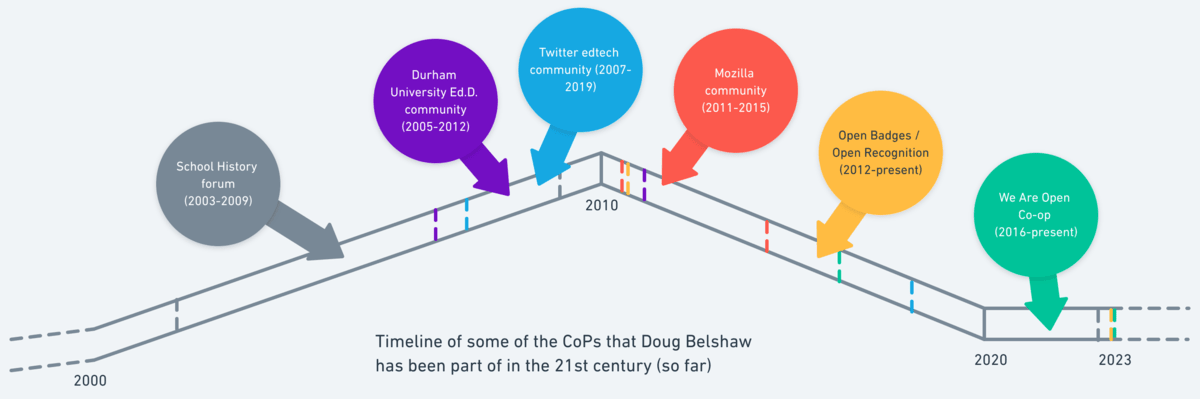

All of this is by introduction to my timeline of the CoPs to which I think I’ve belonged. The timeline is how I see the period from about 2000 to now, in my head. For some reason there’s always a ‘turn’ at the end of a decade. I’m never sure why it goes the direction it does. As my wife says, I’m weird.

It’s important to note that this is meant to be in some way three-dimensional. There are no ‘peaks and troughs’. I could have spent longer on this to try and get the colours to overlap and interact with one another, but life is short.

I’m currently a member of the Open Education is for Everybody (ORE) and we’re currently working on an Open Recognition Toolkit (ORT) to be launched at ePIC 2023. This is what CoPs do: they come together to talk, share information, and create resources. By doing this, members encourage one another.

Reflecting on my membership of different communities, I turned from a lurker into an active community member due to the specific invitation of someone to start posting on the School History discussion forum. That was a revelation to me, as I then had a community beyond the walls of the school in which I was working. It transformed my practice, and the ‘audience’ for the work I was doing went beyond the stakeholders of my organisation (a school) and into the wider world.

Likewise, this set the scene for sharing my work openly on my blog and via Twitter, which is the best CoP I’ve ever been part of. It’s easy to consider social networks to be, well, networks but they can foster people coalescing around hashtags, and around practices such as online chats on particular topics at certain times. There’s a boundary that can be drawn around the practice.

My volunteering for Mozilla led to being employed to them. I still go along to MozFest and would consider myself a ‘Mozillian’ which, I guess, is part of a community identity — even if it has changed quite a lot over time. One of the most fulfilling communities I’ve been part of has been the Open Badges community which has morphed into Open Recognition when ‘microcredentialing’ sucked the life out of the original vibe.

And then, of course, there’s We Are Open, the cooperative I co-founded with friends and former colleagues in 2016. This has been a wonderfully sustaining organisation for me, starting off as a part-time thing, and then evolving into something I do ‘full time’ (for some definitions of ‘full’). This is very much a community of practice as we work together on a daily basis, evolving what we do as we learn from each other, our reading, and our work.

In closing, I’d note that the CoPs I’ve been involved in have had a ‘boundary’. That’s what gives them the domain of practice. Membership has been clear, as has (usually) what we’re working on. What CoPs do, in my experience, even if I haven’t always realised I’ve been part of one, is elevate my aspirations and interest in my practice. They’ve stimulated and encouraged me to go further in the work that I do, knowing that I’ve got an audience for the things that I find frustrating or fascinating.

I’m looking forward to being part of a Systems Thinking CoP. I guess the TB872 module is one, although I don’t feel very connected to fellow students yet. Perhaps I should post more in the forum.

Top image: DALL-E 3