TB872: Juggling the E-ball (Engaging)

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category. This particular post is part of a series which is framed and explained here.

Chapter 6 of Ray Ison’s Systems Practice: How to Act focuses on the E-ball (Engaging). This concerns engaging with real-world situations and involves the practitioner’s choices in orientation and approach, affecting how the situation is experienced. In this post, I’m going to reflect on what I’ve learned in this chapter, applying it to Systemic Inquiry 1 (me as a learner developing my systemic practice) and Systemic Inquiry 2 (my ‘situation of concern’).

Systemic Inquiry 1

The main thrust of Chapter 6 is that we all have a choice about how we engage with situations. This applies both to my own development of systemic practice (S1) and also the situation of concern I’ve chosen to use as an example (S2). I’ll deal with the former now and the latter in the section below this one.

I guess it’s fair to say that I strive for Gramsci‘s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”. This results in me usually bordering on the pessimistic side; as my mother used to say “that means you can always be pleasantly surprised”. One example of this is in framing things as ‘problems’, which is something that Ison deals with early on in Chapter 6. He suggests there is more to be gained in either describing them differently, or at the very least describing them.

One way of describing ‘problems’ different is to compare and contrast ‘wicked problems’ or ‘tame problems’. Ison would reject this, however, in favour or ‘wicked and tame situations’. I can see why this is useful, and these days can also see why neologisms can be handy. I used to think that the latter, which involves coming up with new words or terms, was a waste of time. However, since doing some work on ambiguity alongside my thesis, I’ve come to see the value of them.

As I remarked in a previous post, I tend to ‘give up’ in the face of institutional bureaucracy, and that’s particularly true with regards to ‘wicked problems’, as defined by Rittel and Webber (1973, quoted in Ison, p.122) which the Australian Public Service Commission describe as “beyond the capacity of any one organisation to understand and respond to” (quoted in Ison, 2017, p.121). These are contrasted with ‘tame problems’ which, for example, “have a relatively well-defined and stable problem statement” (Conklin, 2001, quoted in Ison, p.123).

This is presented somewhat as a binary in the chapter — as a choice between describing a situation as unique, ill-defined, and involving multiple organisations (‘wicked’), and a situation which is similar to others, well-defined, and involving perhaps only a single organisations. Surely these must be on a spectrum? Some problems or situations must be more ‘wicked’ or ‘tame’ than others?

I guess the issue is less with definition and more with action: i.e. what are you going to do about it. This is where the idea of ‘goal finding’ rather than ‘goal setting’ comes in (Ison, 2017, p.124, fn.5) which is coming up time and again in my work at the moment. Clients understandably want ‘results’ but sometimes fail to grasp is that heading off in the wrong direction because you’ve chosen a destination without fully understanding a situation doesn’t lead to great results. This is one of the reasons I’m interested in systems thinking diagrams, because they help make visible the thought processes and mental work that we do.

People and organisations don’t tend to call in outside help unless they realise they need it. One situation which they might find themselves is what Russell Ackoff describes as a ‘mess’. These are distinct from ‘problems’:

A mess is a set of external conditions that produces dissatisfaction. It can be conceptualised as a system of problems in the same sense in which a physical body can be conceptualised as a system of atoms.

Akoff (1974), quoted in Ison (2017, p.128)

In my work with WAO, we often use the image above to talk about how we will help ‘untangle’ the ‘spaghetti’ of organisations. In other words, we’ll help sort out their mess. Up until now, however, although I am a somewhat intuitive systemic thinker, a lot of what we have done has been systematic.

One of the things that has always frustrated me about consultancy work is that you are often brought in to help with one particular issue, but it is of course so enmeshed with others within the organisation. However, there is usually a level of resistance in widening the scope of what you’ve been asked to do. This is when the idea of trojan mice can be useful!

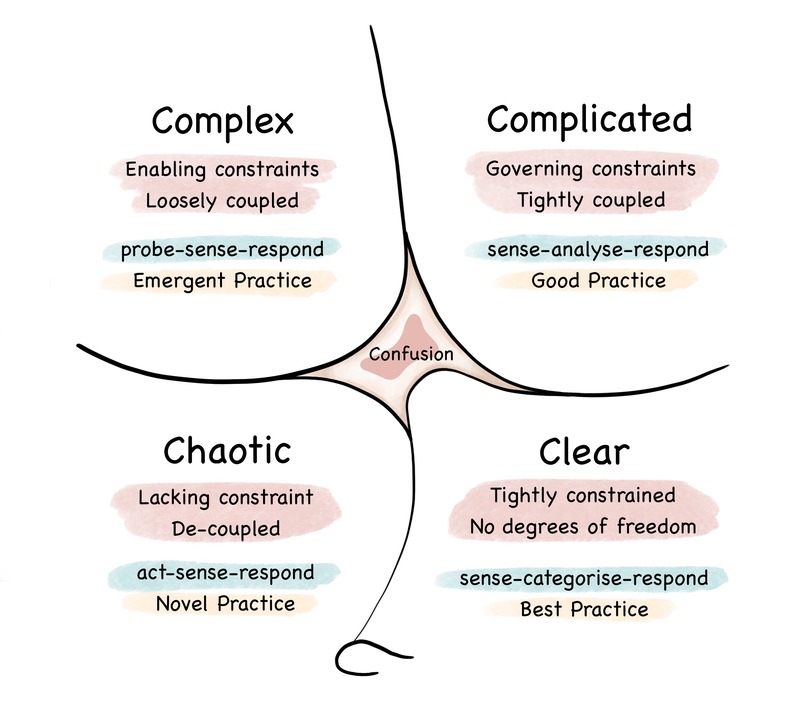

When reflecting on my systemic practice using the E-ball, it’s interesting to think about how often I default to a particular approach. This is what Dave Snowden would call ‘sense making’ which is part of his Cynefin framework, which comes from the Welsh word for ‘habitat’. A slightly different version to the one found in Chapter 6 can be found below.

Snowden says that:

It is not a categorisation model in which the four domains are treated as four quadrants in a two by two matrix. None of the domains described is better than or desirable over any other in any particular context; there are no implied value axes.

IBM (2003), quoted in Ison (2017, p.135)

I’d suggest most organisations, when they get to a certain size, have elements of all four domains. If the leadership of those organisations isn’t careful, then this ends up with some kind of ‘meta-mess’ and confusion. This explains why you can have different departments within an organisation who all have processes and approaches which suggest they know what they are doing, but overall, the organisation under-performs.

Ison says several times in Systems Practice that we need to be careful with our use of language when talking about systems. There is no ‘it’ which objectively exists, be it a ‘mess’ or a ‘situation’ or even a ‘system’. These are all dependent on our subjective view as practitioners and our tradition of understanding. So by referring to an ‘it’ (as in ‘it is a mess’) we are hiding something else — as in the phrase “every noun obscures a verb”.

We’re perhaps familiar with the approach of ‘reframing’ a situation to prevent something being hidden or obscured, but I hadn’t come across the term ‘deframing’ before. This is described as “identifying framings that constrain or stop systemic innovation and change —and warrant active removal — e.g. clean coal” (Ison, 2017, p.131). What Ison is saying here, I think is that deframing is almost a conjurers disappearing trick; in the example he gives, it’s an attempt to remove something from the mental categorisation ‘problematic’.

Other than the reading which takes up a good chunk of Chapter 6, there were two other things that caused me to reflect on my own practice. The first was Donald Schön’s metaphor which contrasts the “swampy lowlands” featuring “messy, confusing problems [which] defy technical solution”, with the “high ground” featuring problems which are “relatively unimportant to individuals or society at large”, however great their technical interest may be” (Schön, D., quoted in Ison, 2017, p.131-132)

This section really spoke to me in terms of my career. Ison shares another quotation from Schön where he talks about the high ground versus the swampy lowlands. These days, it could be argued that I spend my time on the latter, whereas as a teacher I was more involved in the latter:

When teachers, social workers, or planners operate in this vein, they tend to be afflicted with a nagging sense of inferiority in relation to those who present themselves as models of technical rigor. When physicists or engineers do so, they tend to be troubled by the discrepancy between the technical rigor of the ‘hard’ zones of their practice and apparent sloppiness of the ‘soft’ ones. People tend to feel the dilemma of rigor or relevance with particular intensity when they reach the age of about 45. At this point they ask themselves: Am I going to continue to continue to do the thing I was trained for, on which I base my claims to technical rigor and academic respectability? Or am I going to work on the problems — ill formed, vague, and messy — that I have discovered to be real around here? And depending on how people make this choice, their lives unfold differently.

Schön (1995), quoted in Ison (2017, p.132)

Wow. I’m 43 years young and, let me tell you, that feels like he’s peered into my soul.

The second ‘other’ thing I wanted to reflect on was also a metaphor. In this case, it is an observation attributed to Richard Dawkins:

If I hold a rock, but want it to change, to be over there, I can simply throw it. Knowing the weight of the rock, the speed at which it leaves my hand, and a few other variables, I can reliably predict both the path and the landing place of a rock. But what happens if I substitute a [live] bird? Knowing the weight of a bird and the speed of launch tells me nothing really about where the bird will land. No matter how much analysis I do in developing the launch plan … the bird will follow the path it chooses and land where it wants.

Plsek (2001), quoted in Ison (2017, p.134)

Ison says he is “constantly amazed” that this story seems “so profound for many audiences”. I think that says more about his experience and the level he is operating than anything else. The bird/rock anecdote is an extremely good way of bringing to life why, for example, goal finding is more important than goal setting. It’s also a valuable way of showing just how little we humans know about the world.

The E-ball is a reminder that we can choose to engage in situations in different ways. While I already knew this, I would often assume that there was a ‘correct’ way to do so. What this chapter has helped me realise is that everything is contingent, but because there is no ‘view from nowhere’, we have to have some kind of organisational framework to operate in the world.

Systemic Inquiry 2

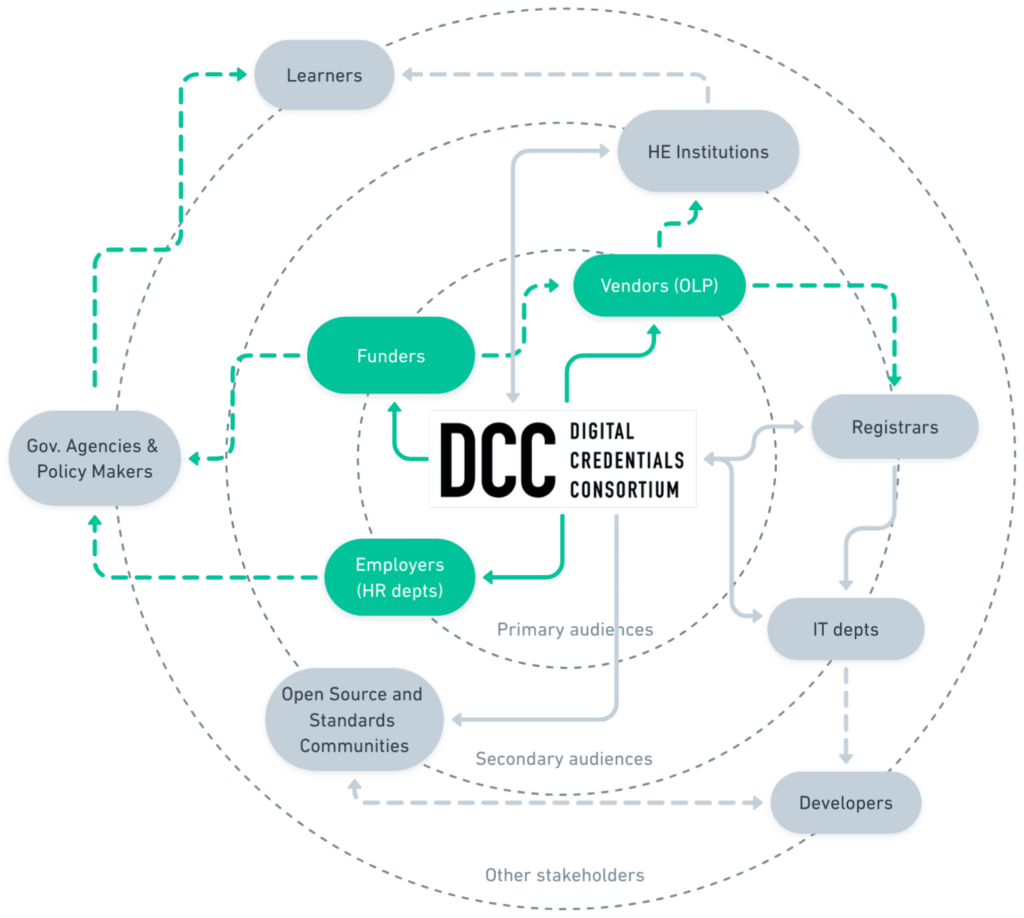

As a reminder, the situation of concern I have chosen to focus on for my Systemic Inquiry 2 (S2) is the work that We Are Open Co-op (WAO) is doing with the Digital Credentials Consortium (DCC) around Verifiable Credentials (VCs). We’re helping with documentation and asset-creation.

One of the interesting metaphors Ison uses towards the start of Chapter 6 is that of a ‘tornado’:

[A] tornado is a particular dynamic configuration of air particles, from which a tornado ‘as named thing’ emerges and is constantly reconstituted.

Ison (2017, p.120)

This is qualitatively similar to the Ship of Theseus, just on a much slower scale. I remember as a teenager being introduced to this paradox and realising that everything is in flux, Just as Heraclitus said. This being the case, there is nothing that we can point to which is quantitatively identical to what existed previously; we can only point to qualitative similarities.

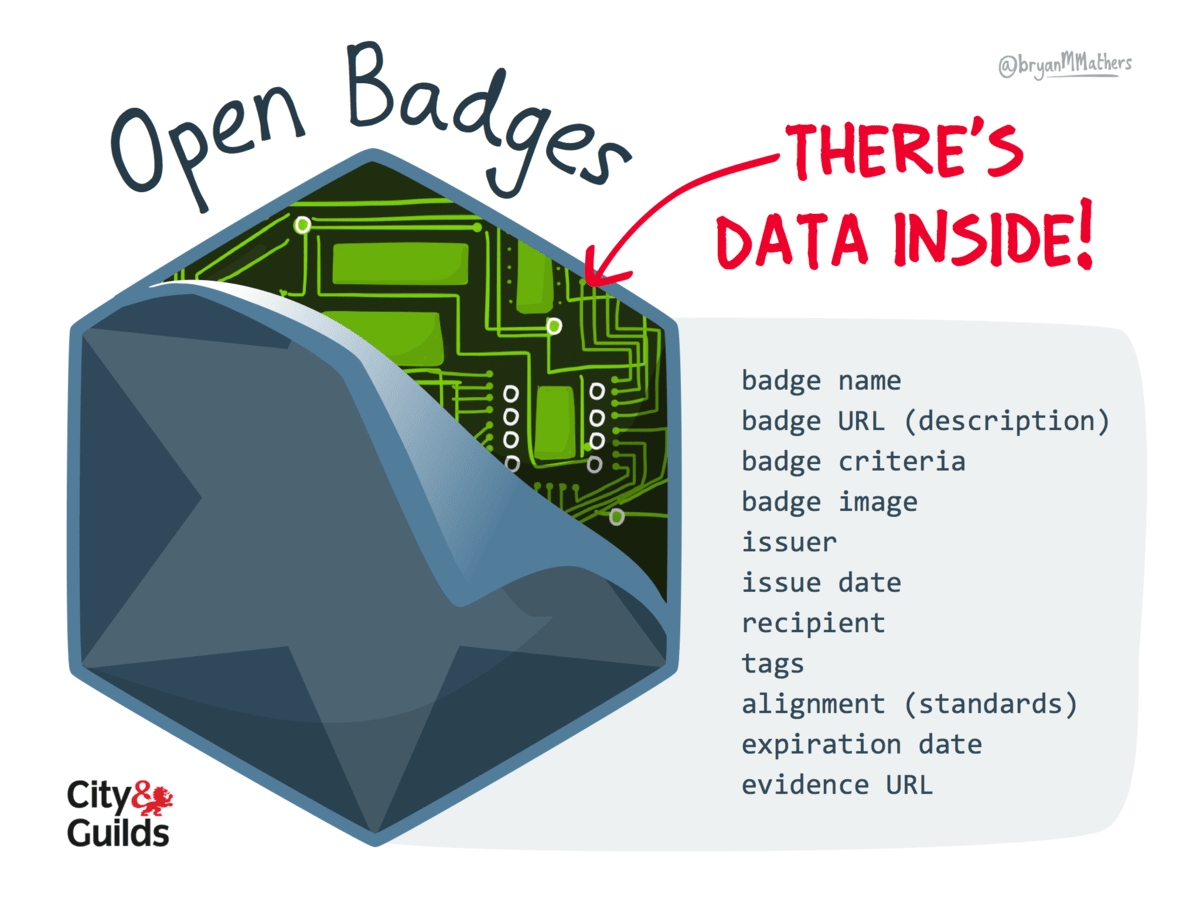

Finding space to move things in a new direction is where neologisms come in, as mentioned in the previous section. Ison talks about how these give “rise to a new expression as well as a new underlying logic” (Ison, 2017, p.120). This is a particularly interesting way of looking at things in terms of my S2. As I mentioned in a previous post, microcredentials can perhaps be seen “can be seen as a reaction to, and reconceptualisation of, Open Badges”. I know that when I was on Mozilla’s Open Badges team, and it was my job to go off an evangelise them, there were plenty of people who really didn’t like the term ‘badge’.

Eventually, I learned to say that it doesn’t matter what you call the digital credentials that you build upon the Open Badges standard. The important thing is that there’s a standard that it’s built on. But, by that time, I think it was a bit too late. This newer terminology around Verifiable Credentials started life as ‘Verifiable Claims’ which, again, was language people didn’t particularly like. There’s a desire for certainty, and VCs sound like the kind of thing that prestigious, trustworthy institutions issue.

In this post, I explained the changes I hope to see in my S2. The first of these, and perhaps the most important, is “greater understanding within the HE sector of what VCs are and how they can be used”. The trick, I think, is to find the right mental models and neologisms which help people conceptualise what’s going on. In doing that we need to ensure that the distinctions we create are for the benefit of understanding and not simply branding exercises (Ison, 2017, p.152). I’ve already mentioned how every noun obscures a verb (Ison, 2017, p.136) and this is certainly true of ‘credential’ versus ‘credentialing’ (or even ‘recognition’).

Before I realised that the reason that I was attracted to Open Badges was because of the Open Recognition which underpins it, I was a little too focused on the ‘badge’ itself. What I’ve come to understand through reading Chapter 7 about the E-ball is that we have to be careful not to reify things. That is to say, we should not “make or treat an abstraction, such as justice or learning, as a concrete material thing” (Ison, 2017, p.131).

[W]e project our meanings into the world [through living in language] and then we perceive them as existing in the world, as having a reality of their own.

Wenger (1998) quoted in Ison (2017, p.131)

When I apply this to my S2, it’s easy to see how people can be confused. Right now, even I would take a minute to explain the difference between Open Badges 2.0, 2.1, and 3.0. The last of these is compatible with the Verifiable Credentials data model. There’s also the Comprehensive Learning Record, which is a separate, but compatible standard. Digital credentials can be any of these, as can microcredentials, with the latter usually relating to a course with a credential at the end of it.

As a result, whereas sometimes we need to create neologisms to free up some conceptual space for some productive ambiguity, in this case we’re trying to actually help people understand what VCs are. In this case we need to use metaphors to do this. It’s just important to ensure these don’t turn into ‘dead metaphors’ by too closely associating just one of them with VCs. For example, I’ve heard the metaphor of an ‘envelope’ used quite a lot. But they are not literally envelopes, so it’s important to use multiple metaphors to help people understand in a more ‘three-dimensional’ way.

Often when people reify things it’s because they see them as a ‘difficulty’ (Ison, 2017, p.137). This is the case, for example, when people talk about ‘system failures’ when they’re not thinking about systemic failures but rather systematic failures (“if only people stuck to the rules and procedures!”). As the reading in Chapter 6 shows, it’s possible to be wrong or misguided on several levels. The point is to return with new knowledge to understand and attempt to intervene in the system differently.

It’s difficult to summarise the reading, but it was related to public health issues in Nepal stemming from rural agricultural practices being translated to urban environments. Interventions which treated only the symptoms failed, leading to a rethink. Ison outlines six phases, which I will paraphrase:

- Phase 1 – traditional scientific approach where knowledge and practices from other contexts could be applied.

- Phase 2 – development of a model which had a presumed single ‘correct’ perspective.

- Phase 3 – broader framing with local groups joining to widen the perspective.

- Phase 4 – methodological pluralism and involvement of different stakeholders at different levels/scales of the project.

- Phase 5 – introduction of diagramming to engage with the situation and capture systemic depictions of the situation from a wide range of stakeholders.

- Phase 6 – emergent awareness of what can be gained from shift towards systemic practice; drawing on stories for civic engagement.

When I reflect on these phases and thing about my S2, it’s clear that previously I would very much be thinking of the type of approaches that are represented in Phases 1-3 in the list above. Now, however, I’m more aware of the value of things such as methodological pluralism, the value of diagrams to help ‘explain the phenomena’, and wider engagement through storytelling.

I’m particularly keen to move onto one of the next activities that involves influence diagrams. From what I know of them, and my S2 so far, mapping how and why people and organisations influence one another could be extremely valuable. For example, we noticed early in our research and onboarding that what staff members were telling us and what was contained in the reports was slightly, but importantly, different. From this, we did some diagramming to map information flows, realising that vendors were going to be important in terms of influencing university registrars.

In a recent meeting, this was reflected back to us, showing that we are potentially on a productive track. What we need to do is to continue with our user research, of the leadership group, and also of people within the ecosystem. What I’ve come to realise is that there’s not a ‘correct’ way of seeing how everything fits together, just ones which help people make sense of it all. As William James might put it, approaches which are “good in the way of belief”.

Juggling the E-ball in my situation of concern (S2) involves multiple levels of contextualisation. It’s primarily concerned with the US Higher Education system, of which have only second-hand experience. That system, or rather ‘mess’ of systems, it nested inside not only US society and culture, but international education, and a long and deep history of credentialing. There are also technical systems with which any new technologies must be interoperable. What I need to remember is that, while we all want to make the world a better place, people respond to incentives. And the greatest incentive of all, for most people, most of the time, is to make their lives and jobs easier.

References

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems practice: how to act. Springer, London.

Image: DALL-E 3