TB871: Ambiguity and cognitive biases

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

You may have watched this video which was referenced by the brilliant Cathy Davidson in her book Now You See It. But perhaps you haven’t seen, as I hadn’t, a related one called The Door Study. TL;DR: it was one of the first confirmations outside of a laboratory setting of ‘change blindness’. What we perceive is usually what we’ve been primed to pay attention to, rather than simply us sensing data from our environment.

It’s a good reminder that, phenomenologically-speaking, much of what we experience about the external world, such as colour, doesn’t actually ‘exist’ in an objectively-meaningful way. We construct our observation of the environment; everything is a projection. As the module materials quote Heinz von Foerster as saying: “Objectivity is the delusion that observations could be made without an observer” (The Open University, 2020a).

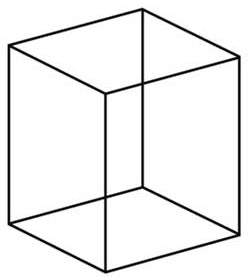

When it comes to systems thinking, this is a key reason why the idea of ‘perspective’ is so important: the world is different depending on our point of view, and we can struggle to see it as being even possible to observe it differently. A good example of this, other than the familiar rabbit-duck illusion is the Necker cube (The Open University, 2020b):

This is literally a flat pattern of 12 lines, so the fact that most of us see it automatically as a 3D object is due to our brains modelling it as such. However, our brains aren’t sure whether we should see the underside of the bottom face of the cube, or the upper side of the top face. As with the rabbit-duck illusion, our brains can see one of these, but not both at the same time.

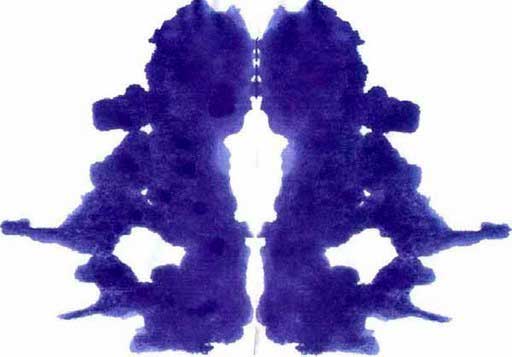

Going further, we can take the ink blot below, taken from the module materials (The Open University, 2020c):

Using this diagnostically is usually referred to as a Rorschach test which many people think is pseudo-scientific. However, it is interesting as a parlour trick to show how people think about the world. For example, I see two people with their hands behind their backs, kissing. I’m not sure what that says about me, if anything!

Spending a bit more time with the ink blot, I began to see it as a kind of eye covering that one might wear at a masked ball. Switching between these two is relatively easy, as the primary focus for each is on a different part of the image.

There are similar approaches to the above, for example the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) created by Henry A. Murray and Christiana D. Morgan at Harvard University, which presents subjects with an ambiguous image (e.g. a photograph) and asks them to explain what is going on.

The rationale behind the technique is that people tend to interpret ambiguous situations in accordance with their own past experiences and current motivations, which may be conscious or unconscious. Murray reasoned that by asking people to tell a story about a picture, their defenses to the examiner would be lowered as they would not realize the sensitive personal information they were divulging by creating the story.

(Wikipedia)

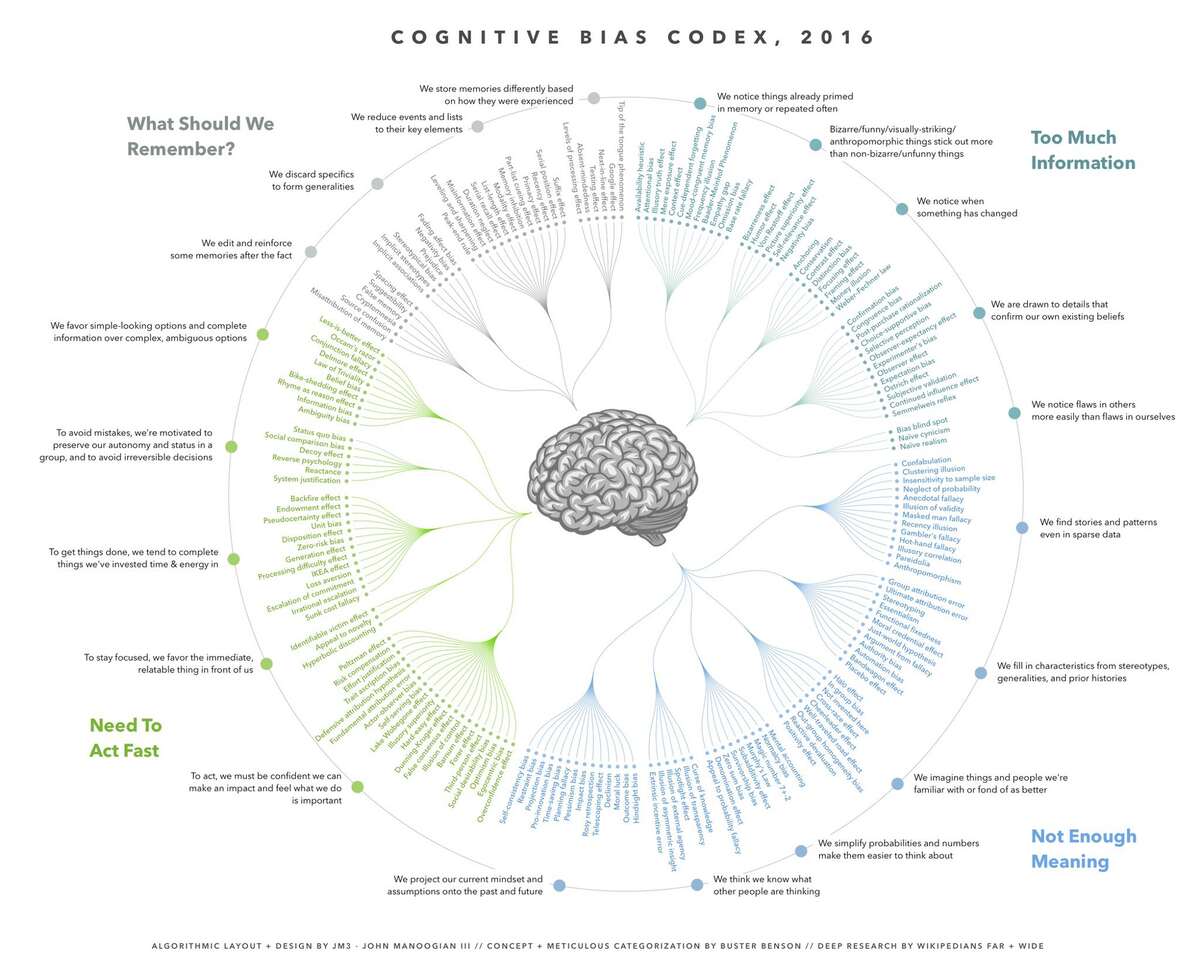

These approaches show how much we construct our understanding of the world rather than just experience it as somehow objectively it is ‘out there’. There’s a wonderful image created by JM3 based on some synthesis by Buster Benson which I had on the wall of my old home office (and will do in my new one when it’s constructed!) which groups the various cognitive biases to which we humans are susceptible:

As you can see, these are boiled down to:

- What should we remember?

- Too much information

- Not enough meaning

- Need to act fast

Here are some of the most common ten biases we are prone to:

- Confirmation bias: Favouring information that confirms pre-existing beliefs while discounting contrary information, often seeking validation rather than refutation.

- Fundamental attribution error: Overemphasising personality-based explanations for others’ behaviours and underestimating situational influences, particularly noted in Western cultures.

- Bias blind spot: Believing oneself to be less biased than others, exemplifying a self-serving bias.

- Self-serving bias: Attributing successes to oneself and failures to external factors, motivated by the desire to maintain a positive self-image.

- Anchoring effect: Relying too heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the anchor) when making decisions, influencing both automatic and deliberate thinking.

- Representative heuristic: Estimating event likelihood based on how closely it matches an existing mental prototype, often leading to misjudgment of risks.

- Projection bias: Assuming others think and feel the same way as oneself, failing to recognize differing perspectives.

- Priming bias: Being influenced by recent information or experiences, leading to preconceived ideas and expectations.

- Affinity bias: Showing preference for people who are similar to oneself, often unconsciously and based on subtle cues.

- Belief bias: Letting personal beliefs influence the assessment of logical arguments, leading to biased evaluations based on the perceived truth of the conclusion.

Of course, just having these on one’s wall, or being able to name them, doesn’t make us any less likely to fall prey to them!

References

- The Open University (2020a) ‘P3.2.3 Sound, light and colour’, TB871 Block 3 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261488§ion=3.3 (Accessed 10 July 2024).

- The Open University (2020b) ‘Necker cube’, TB871 Block 3 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261488§ion=3.4.1 (Accessed 10 July 2024).

- The Open University (2020c) ‘Ink-blots’, TB871 Block 3 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261488§ion=3.4.2 (Accessed 10 July 2024).