TB872: Juggling the B-ball (Being)

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category. This particular post is part of a series which is framed and explained here.

Chapter 5 of Ray Ison’s Systems Practice: How to Act focuses on the B-ball (Being). This concerns the practitioner’s self-awareness and ethics, and involves understanding one’s background, experiences, and prejudices. In this post, I’m going to reflect on what I’ve learned in this chapter, applying it to Systemic Inquiry 1 (me as a learner developing my systemic practice) and Systemic Inquiry 2 (my ‘situation of concern’).

Systemic Inquiry 1

One of the things we’re encouraged to reflect on in this module is our ‘tradition of understanding’. Mine is informed both by my academic studies and my lived experience. The former is mainly focused on the Humanities (Philosophy, History, Education) and the latter includes navigating different codes, having grown up in a middle-class household in a deprived, working class area, and experiencing various situations in life including some life-changing CBT.

I mention this because Table 5.1 in Chapter 5, which is based on the work of Lakoff and Johnson (1999), compares and contrasts the ‘Traditional Western conception of the disembodied person’ with ‘The conception of an embodied person’. The first column includes assumptions around such things as the existence of an objective world. It also mentions ‘ and ‘universal reason’ and the widely-held view that our ability to use this is what separates us from ‘the animals’.

The second column contrasts with this, with statements around the subjectivity of the world based on embodied understanding. For example, one entry reads “we can only form concepts through the body” and foregrounds “primary metaphors” which are “unconscious, basic-level concepts”. Essentially, it is arguing against a Cartesian mind-body duality, suggesting that our understanding of the world is mediated by our sensorimotor system. As such, our bodies shape our understanding.

Yesterday, I listened to an episode of Adam Grant’s WorkLife podcast which featured Lisa Feldman Barrett, a psychologist and neuroscientist. She was talking about how our brains are trapped in our skull and essentially ‘guess’ what’s happening in the world based on sensory inputs. The argument she was making was for greater ’emotional granularity’, as our brain attempts to make sense of new data based on what we’ve experienced before. If we use large buckets such as ‘unhappy’ or ‘unwell’ then our brain doesn’t tend to match our current situation with a relevant one from the past. This can cause problems.

This podcast episode reminded me of the B-ball discussion in Chapter 5, as it relates to my Systemic Inquiry 1. Because we ‘live in language’, including that which we use internally for private thoughts, language shapes our understanding of the world. As such, new information doesn’t necessarily change behaviour, as our emotions and understanding of the world are not directly altered by getting the most accurate data. What the brain is often trying to do is to do the thing which is metabolically least expensive. So if that means erring on the side of caution, then so be it.

What I liked about Chapter 5 was that it seemed to draw on lots of things I’ve learned over the years — as well as recently — and put it all together. For example, I’ve long been a fan of Richard Rorty’s Pragmatism, and indeed Rorty is quoted in this chapter:

If we see knowing not as having an essence, to be described by scientists or philosophers, but rather as a right, by current standards, to believe, then we are well on the way to seeing conversation as the ultimate context within which knowledge is to be understood.

Rorty (1980), quoted in Ison (2017, p.96)

The “by current standards” is important here. It’s the reason why we might be ‘historically disappointed’ by the actions of our ancestors, but given the milieu of the time, it might be hard to blame them. Conversely, there are ‘ways of knowing’ that are being lost due to globalisation. Chapter 5 gives the example from a novel (that I didn’t finish) called Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow by Peter Høeg. The story centres around a character called Smilla who is immersed in the history and culture of the Inuit people; she can therefore ‘read’ snow and ice in a lot more detail than others.

Part of this difference stems from whether we see ourselves as looking at the world (or universe) as something separate to it, or whether we are part of it. In broad brushstrokes, this is essentially the difference between our modern, neoliberal, individualistic way of thinking, and a more indigenous, holistic approach. The latter is also promoted by religions such as Buddhism. Having been brought up in the former worldview, I find it very difficult to switch to the latter, no matter how appealing it is.

In terms of my Systemic Inquiry 1, I’d say that Chapter 5 helped bring together different strands which already formed part of my existing tradition of understanding. While I don’t think I interpret my past practice much differently as a result of reading it, the chapter does help in terms of what I am currently doing in my system practice. For example, the reflection on the notion of an ‘institution’ (p.112-113) helps me understand how they can hinder systemic practice by reifying things and acting as a ‘social technology’ (see previous post) to standardise behaviour.

Thinking about my future systems practice, therefore, it’s important for me to stand up for what I know to be correct. I have a tendency to ‘give up’ in the face of institutional bureaucracy. Systems can be changed, and language is an extremely powerful way of doing so. As is saying “I don’t know, but let’s find out” in the face of being asked questions by people in power which, ultimately, are designed to make you feel small.

On reflection, I think I came into this module assuming that we would go through a series of ‘techniques’ for systems thinking which could be applied in different situations. Although it’s important to have a toolbox of such techniques, which perhaps are dealt with via the C-ball, the stance that you take when approaching a new or existing system is particularly important. I shall be bearing that in mind in future.

Systemic Inquiry 2

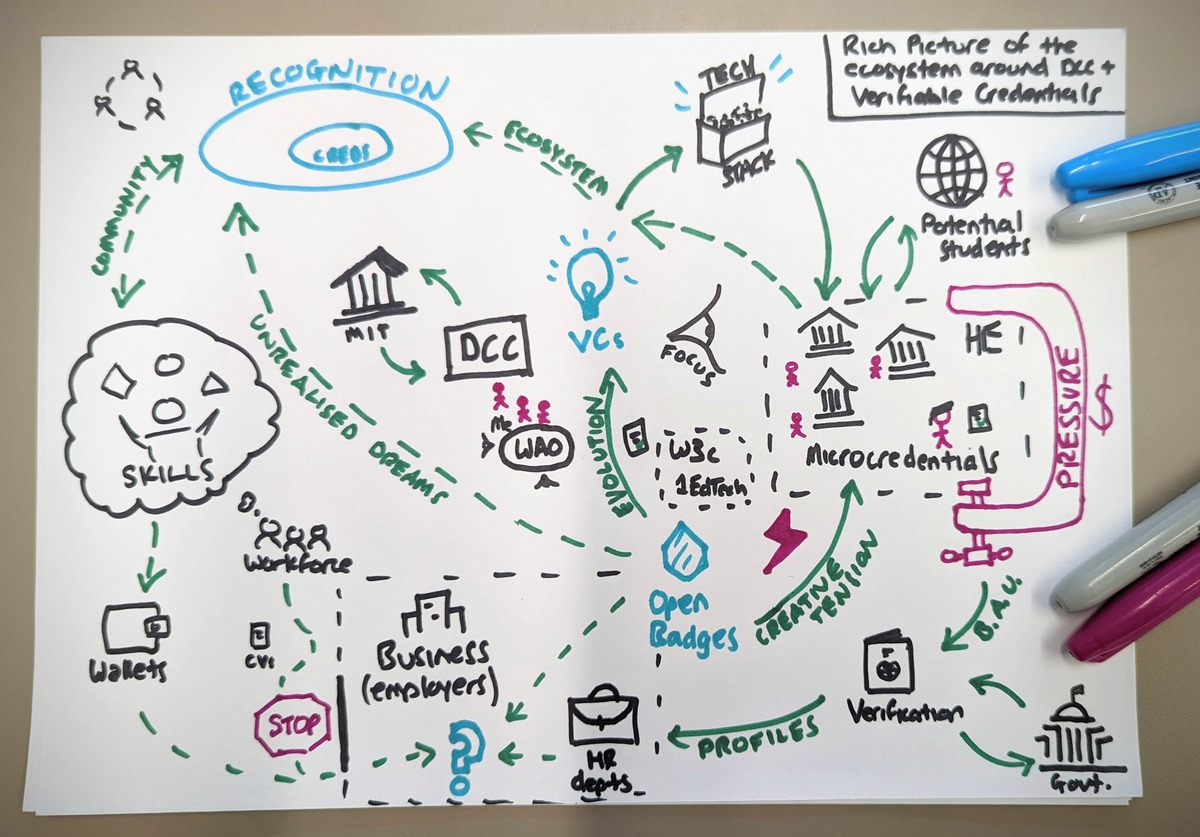

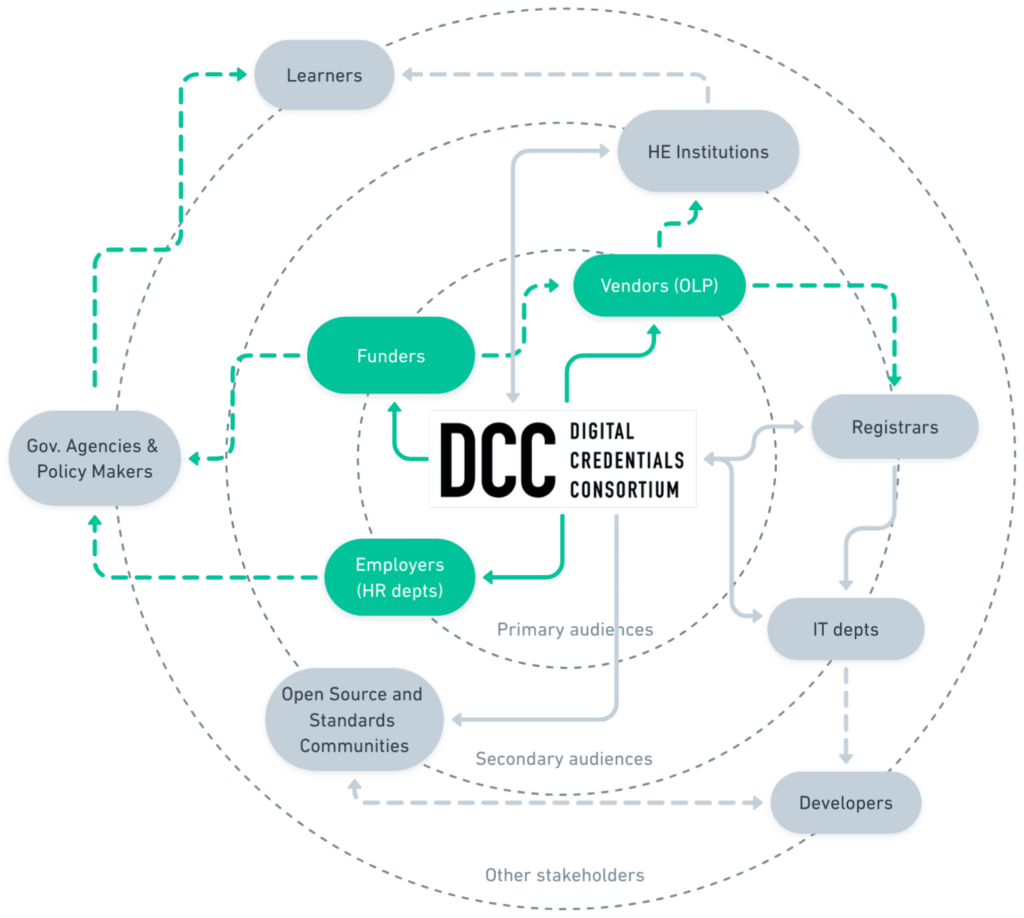

The situation of concern I have chosen to focus on for my Systemic Inquiry 2 is the work that We Are Open Co-op (WAO) is doing with the Digital Credentials Consortium (DCC) around Verifiable Credentials (VCs). We’re working with the Director of the DCC, who we know from previous projects related to digital credentials, to help with documentation and asset-creation. It turns out that explaining these technologies is quite difficult.

One of the things we’ve started to address is the mental models that people use to understand concepts such as VCs, including metaphors and symbolism. We published a blog post about this yesterday. This is an example of purposive framing in that we are interpreting what others in the situation of concern think and do. As we do more user research interviews, and find out what they actually think, this will move to purposeful framing.

I’ve been involved with work around digital credentials for around 13 years when I first heard about Open Badges. My current understanding is therefore coloured by successes and failures that have taken place over the years, as well as systems in which I have tried to intervene. What Chapter 5 has helped me realise is attempts that I and others have made centered on the potential future value of the technologies to creating a fairer society. Meanwhile, most people and organisations care about themselves, an abstract notion of ‘fairness’, and financial sustainability.

For example, around a decade ago, Open Badges was originally presented along with Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) as an existential threat to universities, especially in the US. Unsurprisingly, universities fought back against both, citing concerns around ‘quality’. Fast-forward to today, and most universities have all kinds of online courses and digital credentials. In fact, it can be argued that the term ‘microcredential‘ is essentially a Higher Education re-invention of Open Badges and MOOCs as an online course provided by universities.

Language and relationships are therefore of vital importance when it comes to trying to intervene in a system. It’s possible to be intentional about information flows, as demonstrated in the (unfinished) diagram below, but such abstraction fails to take into account the way that people understand technologies. In the previous example, it would have been entirely possible for universities not to have threatened by Open Badges and MOOCs, and in fact outside of the US, the reaction was different.

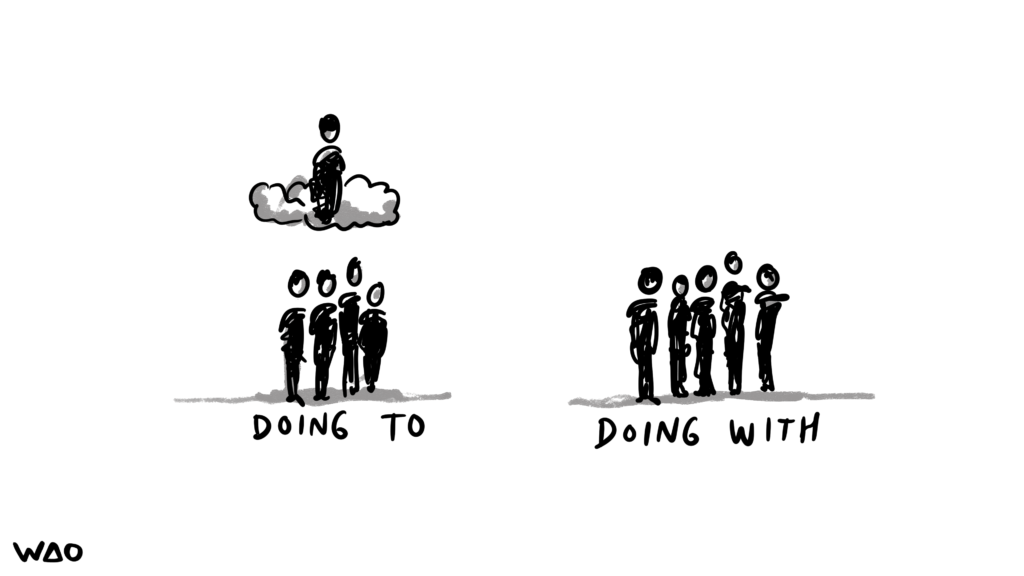

Reflecting on Chapter 5 suggests to me that it is relationships which will be an important way to intervene in this system. Helping the DCC encourage more universities to use VCs involves helping people at those universities understand what the technology involves, hence the work on mental models and metaphors. But it also involves helping those people understanding that they are not simply the victims of historical inevitability and market forces; that they can work together to build a future they would like to see.

It was interesting to witness on a recent DCC community call just how inspired many of the, predominantly US-based, audience was at the work on Diia by the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine. This initiative, which pre-dates the Russian invasion, is a form of e-governance along the lines of Estonia’s E-residency programme. Ukrainian citizens can access most government documents, including driving license and passport, using the app and web portal. Soon, they will also be able to do this for their university degrees.

In my studies so far, although I’ve read a lot about the relational aspect of systems, I haven’t seen or heard the word ‘inspiration’. Yet this is so important when it comes to behavioural change. It’s the reason that a reasonably-average football team can win a cup game against better opposition. It’s also a reason why people and organisations can transcend the current problems and malaise within a landscape, working together to build a system to change something specific.

Chapter 5 makes me realise how fortunate we are to be able to go into this work with the DCC being known and trusted enough to be able to feel our way forward a bit, and to present provisional and tentative conclusions in our meetings with the director. This stands in stark contrast to the proposal we sent as a response to an Invititation to Tender this week, which had us answering questions and providing evidence in a very regimented way. In addition, as is usual with these things, we had to present a project plan without having much context. Understood through the lens of embodied ways of knowing, it seems like an approach designed to create maximum stress rather than maximum understanding.

In the situation of concern relating to the DCC, we have identified our stakeholders and have started to talk with them in semi-structured user research interviews. We’re asking relational questions such as what motivated people to first engage with the DCC and VCs in general, as well as human interactions they’ve had, and ways in which they think we could speed up adoption. This chapter has also made me think that we need to dig even more into what they are trying to achieve. As I mentioned above, my assumption is that people tend to be motivated by problems and concerns that directly affect them. So if we can find those ‘pain points’ we can start explaining how VCs and the reference technologies offered by the DCC can help with these.

Finally, it’s worth saying that my Systemic Inquiry 2 is not only informed by Systemic Inquiry 1, but also other systems which involve other practitioners. For example, as I’ll explore when we get to other chapters, my interactions with other members of WAO, with members of adjacent communities, and with our client are particularly important in shaping a way forward for the inquiry and wider project.

References

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems practice: how to act. Springer, London.

- Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: the embodied mind and its challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books, New York.

Image: DALL-E 3