TB872: Systemic inquiry as a social technology

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

If projects are so problematic, and we need more emotion in our decision-making, then what should we do instead? This post focuses on Chapter 10 of Ray Ison’s book Systems Practice: How to Act, which begins with a list of the kinds of things people who want to use an alternative approach need to be able to do.

Ison can be wordy, so I’ve asked ChatGPT for a more straightforward version:

- Comprehending the current and historical context of situations.

- Recognising and valuing the diverse viewpoints of multiple stakeholders.

- Clearly identifying and exploring the underlying purpose of actions or decisions.

- Differentiating between the ‘what’, ‘how’, and ‘why’, and determining the appropriate timing for each aspect.

- Implementing actions that are purpose-driven, systemically beneficial, culturally viable, and ethically justifiable.

- Creating a method to harmonise understanding and practices across different locations and over time, especially in situations where initial improvements are unclear, thus managing a dynamic, co-evolutionary process adaptively.

- Sustainably integrating the approach into ongoing practices without oversimplifying or misusing its fundamental principles.

Instead of setting this approach against projects, it’s more of a “meta-form of purposeful action” which provides a “more conducive, systemic setting for programmes and projects”. (See the arrow image above to get the gist.)

We understand systemic inquiry as a meta-platform or process for ‘project or program managing’ as well as a particular means of facilitating movement towards social learning (understood as concerted action by multiple stakeholders in situations of complexity and uncertainty). When conducted with others it can be called systemic co-inquiry.

Ison, R. (2017) Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. pp.252-253. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

Just because the systemic inquiry is ‘meta’ does not mean that it is necessarily bigger or longer lasting than the programmes and/or projects it contains. Nor is the ‘goal’ of systemic inquiry to create ‘a system’; it is an action-oriented approach where the intention is to produce a change.

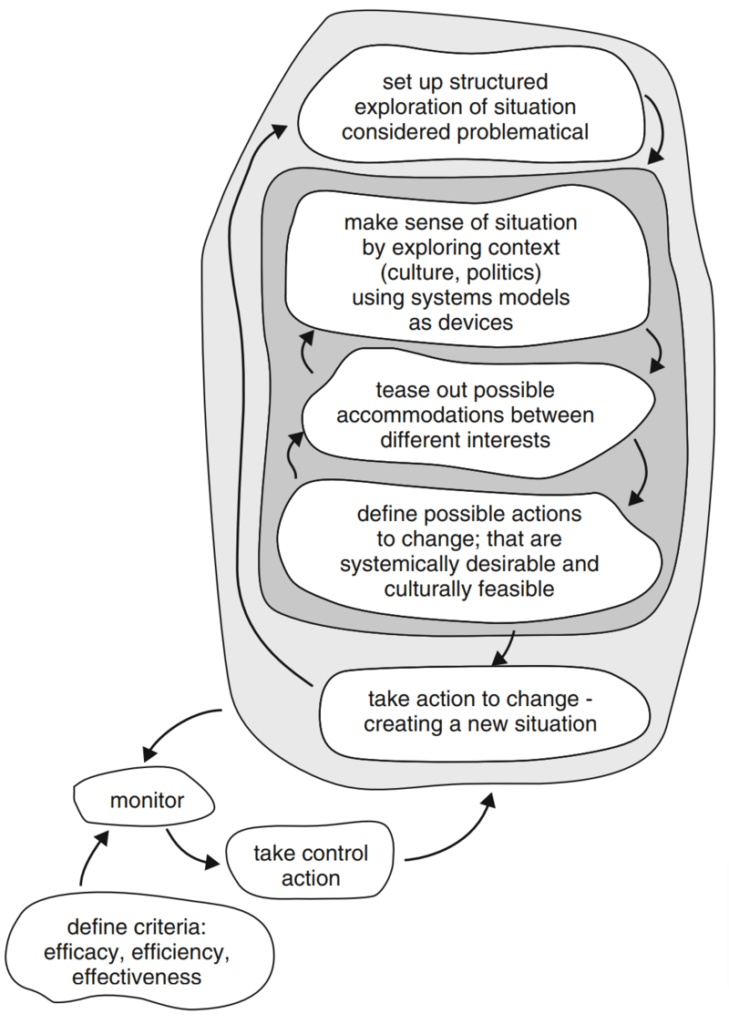

The image below, Fig. 10.1 in Ison’s book (p.256), is an activity model of a system to conduct a systemic inquiry. It has been adapted from Peter Checkland’s work.

If this approach creates a ‘social learning’ then this is a ‘learning system’. But what does that mean? Ison suggests that instead of thinking about it in ontological terms (e.g. “a course or a policy to reduce carbon emissions”) we should think of a learning system as an epistemic device (i.e. “a way of knowing and doing”).

This move constitutes a ‘design turn’, says Ison, away from first-order inquiry (e.g. drawing a boundary to determine what is in/out of scope) to a second-order understanding (e.g. the learning system as existing after its enactment, through human relationships). Both are necessary, it’s just a question of different levels of abstraction and “critical reflexivity”.

Although Ison doesn’t talk about it this way, I guess this is the practitioner (P) reflecting on their own place within a system, making it P(PFMS). See the diagram at the top of this post. When intervening, as an educator, policy maker, or consultant, therefore, there’s a difference between triggering a first-order response (e.g. creating a course or an ‘intervention’) versus a second-order response (e.g. creating the circumstances for people to reflect on their context and take responsibility).

Top image: DALL-E 3 (based on the bottom part of Fig. 10.1 on p.252 of Ison’s book)