TB872: Making choices about situations and systems

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

My last post was about the difference between situations and systems, and about moving from having a systemic sensibility, through to having a form of systems literacy, and then on to systems thinking in practice (STiP) capability. It was a reflection on Systems Practice: How to Act by Ray Ison.

This post picks up where that one left off by discussing Chapter 3. One of the first things to note is that STiP practitioners need to decide a boundary for the system that they create from any given situation. Ison points out that we need to be careful when doing so, and note that:

- We are always in situations, never outside them

- We have choices that can be made about how we see and relate to situations

- There are implications which follow from the choices we make

Ison, R. (2017) Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. p.39. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

The reading in this chapter comes from Dick Morris, a former Open University (OU) colleague of Ison’s. I want to pull out a quotation from it that I thought was interesting:

When thinking in terms of systems, we have at least partially to move away from our usual manner of thinking, which has been heavily influenced by the generally science-based model that has characterised European thought, particularly during the last century. Such thinking in science and its partner, technology, has produced enormous strides in our material well-being, but we also recognised that it has also brought some problems. A key feature of classical science has been to work under carefully controlled experimental conditions, looking in detail at one factor at a time. The success of this approach has unintentionally encouraged a widespread popular belief that we can isolate a single cause for any observed event.

Morris (2005), cited in Ison, R. ibid. p. 40

The examples that Morris gives range from blaming food additives for children’s poor behaviour through to fewer police ‘on the beat’ leading to increased crime rates. I thought this was worth pausing to discuss, especially when coupled with the quotation from John Shotter (1993) that Ison included in a footnote in Chapter 2, and which I also quoted in my last post:

Why do we fell that our language works primarily by us using it accurately to represent and refer to things and states of affairs in the circumstances surrounding us, rather than by using it to influence each other’s and our own behaviour?

Morris (2005), cited in Ison, R. ibid. p. 25

I haven’t time to explore this fully here, so I will just park (for now) the thought that conspiracy theories are a non-scientific way of thinking about the world that nevertheless attempt to ‘explain the phenomena’. By reconceptualising language as “a system to influence others” rather than “a system to accurate describe the world” might we be able to do a better job of working together to improve our world?

As we discovered in Chapter 2, Ison is not a fan of definitions but there is a definition of a ‘system’ in the reading within Chapter 3. Dick Morris (Ison, ibid. p.41) uses one from the OU’s Technology Faculty, which defines a system as:

- A collection of entities

- That are seen by someone

- As interacting together

- To do something

This means that a system is not an indivisible entity, but that it has parts or components and these components interact with one another to cause change. The difficult thing is drawing a boundary and deciding which components to include in a system. For example, is a farm a system to produce food? to produce a profit? to maintain a particular landscape?

We can’t solve all of the problems of the world in one go, and indeed setting a boundary so that the system is too large is self-defeating. As Morris says, “Choosing an inappropriate boundary, and with it, inappropriate criteria, can be misleading” (Ison, ibid. p.43). He gives the example of using animals for food production which, as a vegetarian, I don’t endorse and so won’t repeat here. I don’t think that murdering animals because it might be in some way “sustainable” can be justified.

One thing that is worth quoting from Morris is why STiP practitioners tend to use diagrams (my emphasis):

In order to share our visions, and to debate futures, we need to have some way of explaining what we regard as the system of interest and its key features. We need to have some model of the system which is necessarily simpler than the whole, complex situation itself, but shows what we think are the important aspects. It may be possible to do this in words, but often it is much quicker and more powerful to use some sort of diagram. Words have to flow in a sequential manner to make sense, and one of the features of most systems is that the interactions between entities are often recursive, that is they form loops, where A may affect B, which in turn affects C, but C can also affect A. In such a situation, a diagram can literally be ‘worth a thousand words’!

Morris (2005), cited in Ison, R. ibid. p.43

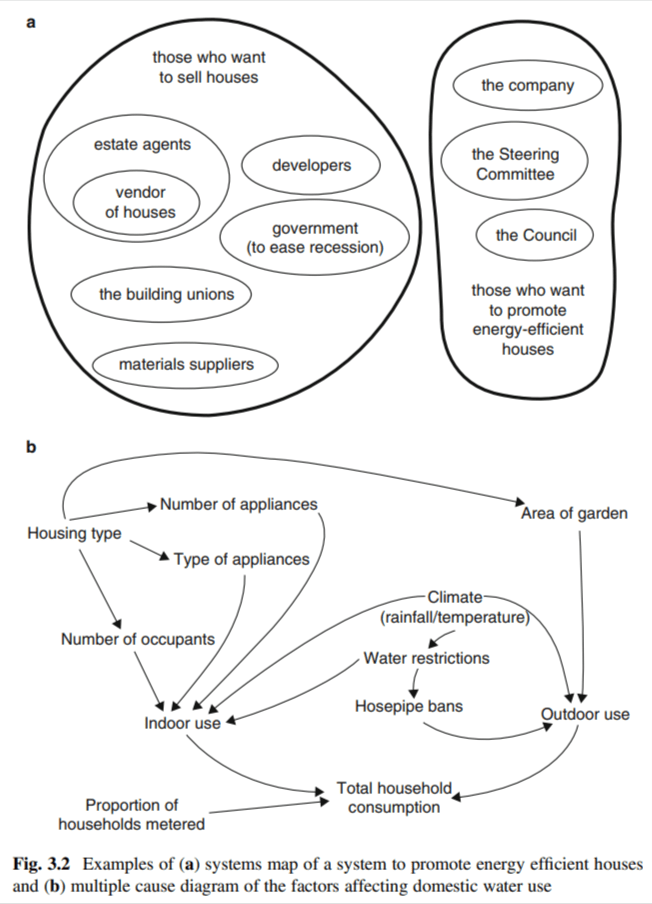

Two examples of diagrammatic forms that can be useful in this regard are given by Morris as Systems Maps (the first example below) and Multiple-cause (or ‘Causal Loop’) diagrams (the second example):

Morris (2005), cited in Ison, R. ibid. p.44

As we can see, both diagrams tell us much more about a given system, and more quickly, than a page of text could do.

At this point, I want to share a brief anecdote as it will help me reflect on the difference between a situation and a system, and the importance of knowing where to place a boundary. I’m a member of the Green Party, although not currently a very active one. I emailed the Green’s candidate in the upcoming North East Mayoral elections recently asking them to come in behind Jamie Driscoll, who is running as an independent after being kicked out of the Labour party for being too closely aligned with Jeremy Corbyn.

I’m not going to share the details of my emails with the Green candidate, especially as they asked me not to, but suffice to say that they seemed much more interested in the technical details of candidacy and party politics than me. The emails to party members reflect this. While this is perhaps understandable, if we look at language as a way of influencing other people’s behaviour, they’re not doing a particularly good job.

It’s not quite the language of systems, and perhaps I’m reading too much into it, but the latest post by Jamie Driscoll on his website talks of there being “no template” for what he’s doing and that “nobody knows” what the future holds:

There’s no template for running a successful combined authority. Devolution is just a vehicle, you need the right driver. My goal was always to build a zero-carbon, zero-poverty, North East, with thriving modern industries and richer communities. We’re making real progress. And we’ve done this without borrowing money or putting a penny on your council tax bills. People of ordinary means already pay enough tax.

[…]

So what does the future hold? The truth is nobody knows. So, instead of making predictions I’ll make a resolution. To finish the job I started in 2019.

It’s time to finish the job I started…. (26 December 2023) Jamie Driscoll, North of Tyne Mayor. Available at: https://jamiedriscoll.co.uk/news/its-time-to-finish-the-job-i-started/ (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

I guess my point is that to make change we have to embrace uncertainty, and act based on values.

As a segue back to Chapter 3, I’ll just note that one of Driscoll’s key pledges is around a “fully integrated public transport [system] under public control” (Driscoll, 2023). Here, the word ‘system’, as is relatively normal in everyday usage, is a thing as opposed to a process.

A constraint to thinking about ‘system’ as an entity and a process is caused by the word ‘system’ being a noun — a noun implies something you can see, touch or discover, but in contemporary systems practice more attention can be paid to the process of ‘formulating’ a ‘system’ as part of an inquiry process in particular situations.

Ison, R. (2017). Ibid. p.47.

In other words, a system is an epistemological device used to engage with a situation, rather than having any ontological status. As he goes on to say (Ison, ibid. p.54) “contemporary systems practice is concerned with overcoming the limitations of the word ‘system’.” Hence, I suppose, Ison’s use of terms like ‘system of interest’ or ‘a system to x’.

Top image: DALL-E 3