Decentralising the description of skills with OSMT

Skills don’t exist. Not really. They’re a shorthand way of describing human attributes and potentials which break down if you analyse them too closely. That’s not to say that defining skills isn’t “useful in the way of belief” as Pragmatist philosophers such as William James would put it — but rather that they only exist, or represent some “truth”, in as much as they have cash value.

There’s a couple of video games I’ve played for over 20 years, on and off. They’re both football (“soccer”) games, one being EA Sports FIFA and the other Football Manager (these days actually Football Manager Mobile). Both games attempt to quantify various skills and attributes important to the sport.

The above skills or attributes are out of a maximum of 20, and they’ve been handily colour-coded so that those playing the game can see at a glance how strong or weak a footballer is in a particular area.

The example I gave above of a video game neglects other things that real-life football teams can and do look for in players they wish to sign. For example, how adept at are they at gaining a social media following? Can they speak to the press confidently? What are they like in the dressing room? Are they volatile?

When we talk about skills in an education or learning and development context, we’re often implicitly talking about them for reasons of employment. Like the footballer represented by colour-coded numbers each out of a maximum of 20, it would make the life of employers a lot easier if they could view job applicants in this way. That’s not to say that they should, it just feels a lot like that’s where we’re heading.

Whoever decides on and controls the numbers is therefore in a very powerful position. They get to decide what is important, provide ways of quantifying those things, and report on them in ways that have real-world outcomes. In this way, it’s very similar to the work I’ve done about digital literacies: whoever gets to decide who or what counts as ‘literate’ holds the power.

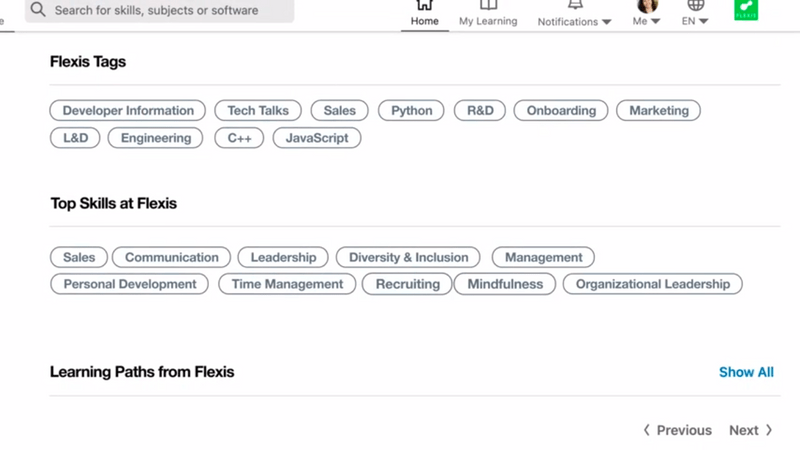

LinkedIn is an example of a company (now owned by Microsoft) that would love to provide this level of quantification of human skills. The screenshot below is from a video embedded in an article from last year announcing their ‘Learning Hub’.

Who defines these skills? Well… LinkedIn do. They control the taxonomy. We should be wary of this.

One of the things that really attracted me to Open Badges more than a decade ago was that it democratises the “means of production” of credentialing and recognition. Although there are always attempts at re-centralisation (this week it was announced that Pearson have bought Credly, one of the major players in the landscape) the whole thing, thankfully, is built on an open standard.

If skills are to be a currency with a cash value, then we need to ensure that the skills represented by badges and credentials are also democratically defined. All of which takes us finally talking about the Open Skills Management Tool:

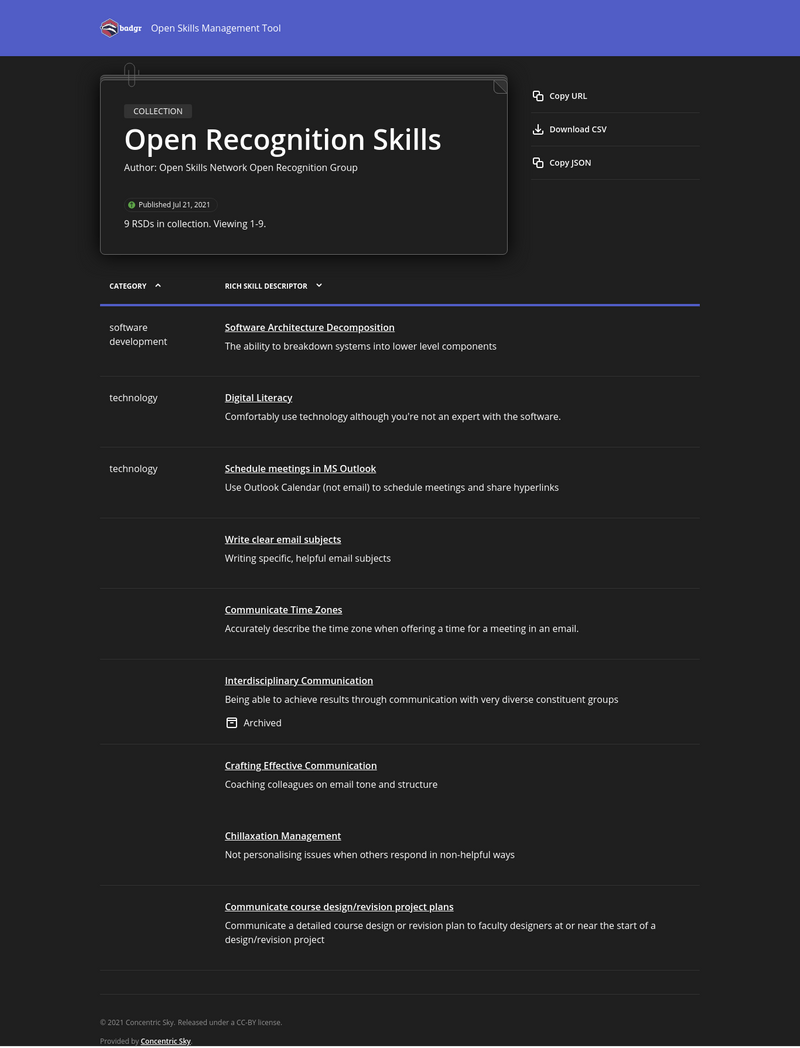

The Open Skills Management Tool (OSMT, pronounced “oz-mit”) is a free, open-source instrument to facilitate the production of Rich Skill Descriptor (RSD) based open skills libraries. In short, it helps to create a common skills language by creating, managing, and organizing skills-related data. An open-source framework allows everyone to use the tool collaboratively to define the RSD, so that those skills are translatable and transferable across educational institutions and hiring organizations within programs, curricula, and job descriptions.

At the heart of OSMT’s functionality are Rich Skills Descriptors (RSDs): machine-readable, searchable data that include the context behind a skill, giving users a common definition for a particular skill. With the open source release of the OSMT, other organizations can now develop and collaborate on individual RSDs as well as on RSD collections.

The power here is in providing common definition for skills within a particular context. This definition, or standard, can then be referenced in the metadata of Open Badges in the AlignmentObject field.

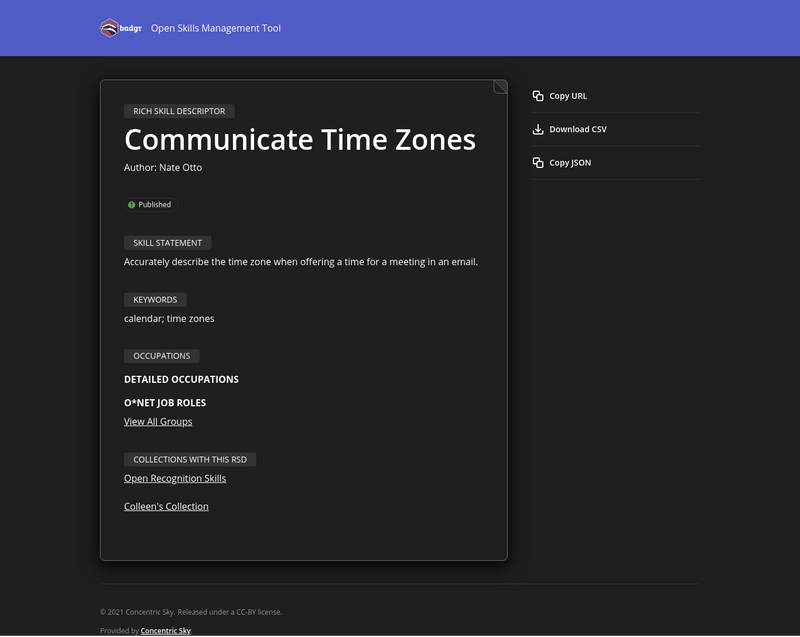

I realise that this sounds rather technical and dry, so let’s look at an example given by Nate Otto during a meeting of the Open Recognition workgroup as part of the Open Skills Network yesterday.

Just like Open Badges, these skills descriptors can be read by humans in words and machines as code (JSON). Let’s look at an example of a skill.

There’s a lot more I could say about this, as there’s a real balance to be struck here between the flexibility that allows a thousand flowers to bloom, and a level of complexity that could stymie innovation.

One of the reasons that I’m moderately excited about the possibilities is that it slots neatly into that AlignmentObject field I mentioned above which is part of the existing Open Badges 2.0 standard. This harks back to work I was doing while at the Mozilla Foundation, linking Web Literacy skills to Open Badges.

Another reason is that Nate and the good people at Badgr are behind it. Not only have they got great people with the best interests of the ecosystem there, but they’ve also got the technical expertise to make it a reality. The next step is to get many, many OSMTs in existence so that we can decentralise the means of skill description!