Enjoy things while they last (or hope for the best, prepare for the worst)

Note: it’s hot, this post might be be more ramble-y than usual…

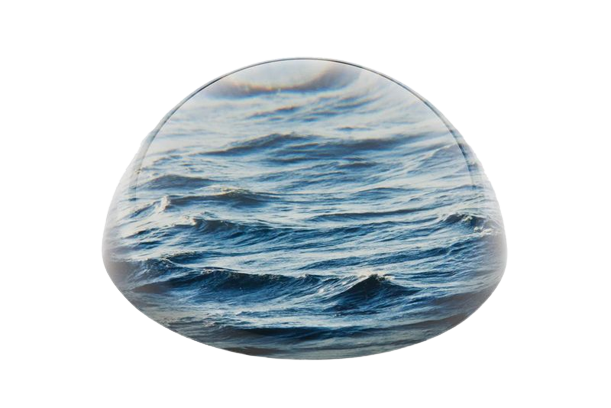

Next to my bed I have one of these:

It’s a glass paperweight that serves as a memento mori, a reminder that one day I will die. That might seem a bit morbid, but it reminds me to carpe diem (“seize the day”, to use another Latin phrase) and that things won’t be this way forever.

My kids will grow up and leave home.

My current state of calm will dissipate.

My possessions will stop working, get lost, or be stolen.

The list is long, for good and bad.

But my reason for writing this post is not a personal one, but a professional one. Right now, I’m more interested in talking about projects and initiatives ‘dying’ than me kicking the bucket. There have been multiple reasons over the past week where I’ve noticed that people expect things that start off great to continue to be so.

An OER repository was sold off to a company whose website is blacklisted by many educational institutions. A popular Android launcher was sold to an analytics company that’s often blacklisted by network blocking software. A project I’ve been involved with looks like it could be in danger of betraying its radical roots.

This is all very predictable, and is the reason for the popular phrase “hope for the best, prepare for the worst”. Especially in the kind of work I do at the intersection of learning, technology, and community, there are some amazing people collaborating on some fantastic things. It just takes a few bad actors (or people with ‘misaligned incentives’ shall we say) to spoil things.

That’s why setting up projects the right way from the beginning is so important. With MoodleNet, for example, we used the AGPL license, which meant that after I and the team resigned due to some internal drama, the Open Source code could form the basis of the project which has turned into Bonfire.

Even without specific licensing, just working openly can have the same effect. For example, there’s an archive of the work I did with a community that I helped grow at Mozilla around the Web Literacy Map. There’s no reference to it any more on the Mozilla site, but I can still reference it myself.

I’m not bitter about these things. (Well, not any more.) My point is rather than you should set up projects and initiatives in open ways, providing ways for awesome, talented people to get involved. But don’t be naive while doing so. Use defensive licenses, like the AGPL, and the wonderful Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike (CC BY-SA) license which forces derivative works to be shared under the same license.

The same is true of legal structure and governance. WAO is set up as a co-operative with a flat structure and Sociocratic decision-making. It’s not possible for one person to sell out our company from underneath us because of the legal structure we created, after taking advice from more senior members of the co-operative community. And we’ve learned that consent-based decision making allows us to make decisions in line with our values.

Processes (especially around decision-making) work… until they don’t. You have to be intentional about these things. Remember that contracts are for when things go wrong, so cover your back. Imagine the worst thing that could happen, and put in place safeguards. Come up with ways to make decisions in productive ways with other people. Share your work far and wide, but protect it using an appropriate license.

Remember that our time on this planet is short, so let’s be awesome to each other.

In case you’re wondering, I bought my memento mori from The School of Life, and while you can’t get this particular one any more, there are others which are great — if not quite as awesome.