TB872: Systemic praxis and epistemological devices

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

As a Philosophy graduate, I’m entirely comfortable both in using terms such as ontology and epistemology, and also unphased when other start throwing them around as well. After all, most of the time, what people are talking about is what exists (ontology), or what/how we can know things (epistemology).

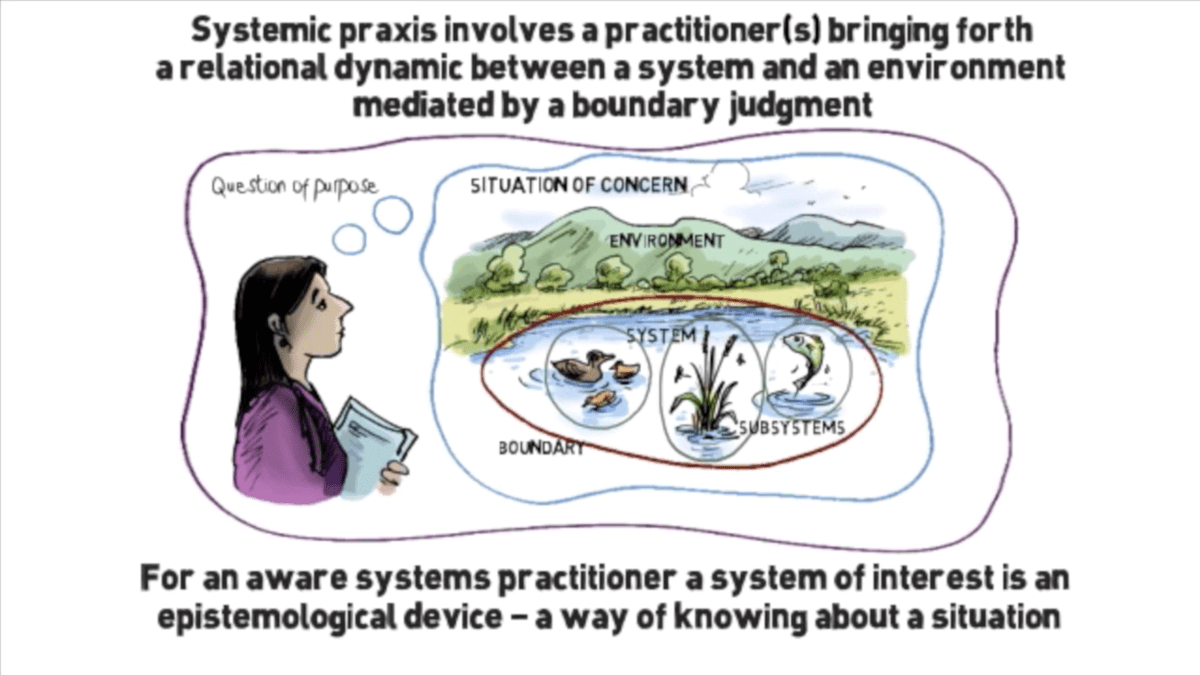

So from a Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP) perspective, it makes sense to be talking about ‘epistemological devices’. These are just ways of knowing about a particular situation. Meanwhile, ‘systemic praxis’ just means ‘theory informed practice within a systems thinking context’.

Putting it all together makes it seem all academic but really all that’s happening is that we’re saying people look at things in different ways because they have different backgrounds and ways of understanding the world. They also are likely to be thinking about things at different scale. In the example above, which is a screenshot from a video on the course, the person/practitioner could be thinking about the pond in terms of the production of fish, or in terms of increasing biodiversity.

In both cases the ‘boundary’ of the system is the pond itself, within a wider ‘situation of concern’. However the purpose is different. The point when drawing diagrams like this isn’t to try and capture some kind of objective view of a situation, which would be impossible. Rather, it’s a good way of helping understand and communicate with others the way you see it.

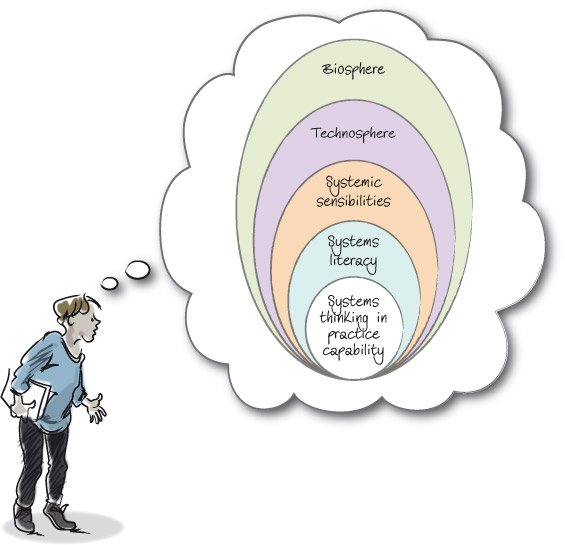

I particularly liked the way that the course authors explained how STiP fits, like Russian dolls, inside wider issues — for example, systems literacy and systemic sensibilities. Crucially, they’re then situated within what is labelled the ‘technosphere’ and the ‘biosphere’. In other words, everything is connected.

In addition, it’s fascinating to see how they break down what they’ve learned about studnets on Systems Thinking-related course over the last 50 years or so. There have been over 40,000 students, and they’ve started to notice some patterns.

A ‘rule of thumb’ is now recognised: about one third of students come with a strongly held systemic sensibility. For this cohort, discovering systems thinking through formal study offers solace, and gives credibility to the way in which they intuitively understand the world. It is a great relief for them to know that they are not alone, that there is a language and concepts that make sense of the way they think. For another third, study of Systems creates ‘aha moments’. This is when realisation dawns that you can appreciate your own thinking … and act to change it. For the final third, the courses lead to a sort of personal precipice, one might say a challenge to their sense of identity, because systems thinking challenges what they are good at or how they have succeeded in their world. Fear of change undoubtedly plays a part.

I’m definitely in the first cohort, the ones with a ‘strongly held systemic sensibility’. The reason I’m finding the module so interesting is because it really gives me for the first time a way of explaining something I find innate.