Flow and the Autotelic Classroom

I’ve mentioned the concept of ‘Flow’ recently after reading Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s seminal work Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. As is often the case with books that are discussed a lot, on the front cover it has a quotation indirectly urging you to buy it. In this case it’s an accurate and brief exhortation from a New York Times review:

I’ve mentioned the concept of ‘Flow’ recently after reading Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s seminal work Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. As is often the case with books that are discussed a lot, on the front cover it has a quotation indirectly urging you to buy it. In this case it’s an accurate and brief exhortation from a New York Times review:

Important… Illuminates the way to happiness.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” I thought. But after reading it, I can confirm that it’s a life-changing book. I’d add the qualifier “at least for me,” but it would seem that pretty much everyone who’s read it agrees. 😀

Being a teacher by both trade and vocation I have, of course, thought of the implications of the concept of ‘Flow’ for my classroom. How can I promote Flow states in my students? There’s certainly a lot of institutional things that militate against it in the average secondary school – not least the ringing of the school bell every 50 minutes! 😮

Being a teacher by both trade and vocation I have, of course, thought of the implications of the concept of ‘Flow’ for my classroom. How can I promote Flow states in my students? There’s certainly a lot of institutional things that militate against it in the average secondary school – not least the ringing of the school bell every 50 minutes! 😮

I was looking through Csikszentmihalyi’s book for a succinct definition of what ‘autotelic’ means, but he teases out the concept throughout his work. That’s not at all a criticism, as he does it well, but it does make it rather difficult to get across in the space of a blog post! Autotelic comes from two Greek words – auto (self) and telos (goal) and ‘refers to a self-contained activity, one that is done not with the expectation of some future benefit, but simply because the doing itself is the reward.’ (p.67) I think the current Wikipedia definition of Autotelic explains the term a little better:

Autotelic is used to describe people who are internally driven, and as such may exhibit a sense of purpose and curiosity. This determination is an exclusive difference from being externally driven, where things such as comfort, money, power, or fame are the motivating force.

These externally-driven motivating forces are known as exotelic, with Csikszentmihalyi keen to point out that most things we do involve combinations of autotelic and exotelic factors.

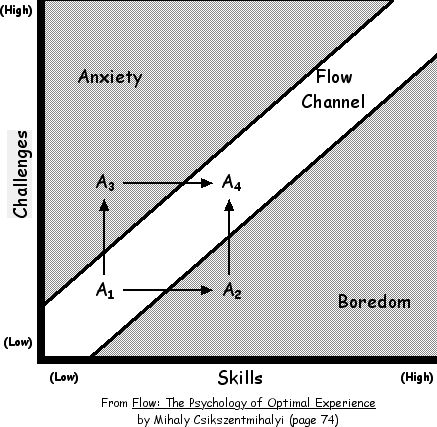

If this difference obtains in the real world – and I think that it does – then it is vitally important that we educate young people how to become more autotelic and therefore achieve Flow states. The idea of Flow is perhaps best summed up by this graph (many thanks to Wes Fryer for making it available under a Creative Commons license via Flickr and including it in his blog post from 2006)

I believe that any educator seeing the above graph for the first time will see something they recognise: the fine line between creating a learning activity and experience that is too easy, too hard, involves too much challenge or involves anxiety for the learner.

The state of Flow, Csikszentmihalyi states, is not good in and of itself, but ‘because it increases the strength and complexity of the self.’ There are good and bad forms of Flow: for example the Marquis de Sade ‘perfected the infliction of pain into a form of pleasure’, but then almost everything and anything can be either good or bad depending on context. In the classroom, allowing one student to achieve a Flow state should not be to the detriment of another.

Csikszentmihalyi sets out four ways in which those who have developed autotelic habits can transform ‘potentially entropic experience[s]’ into Flow states. These quotations are taken from pages 209 to 213.

1. Setting goals

A person with an autotelic self learns to make choices… without much fuss and the minimum of panic… As soon as the goals and challenges define a system of action, they in turn suggest the skills necessary to operate within it… And to develop skills, one needs to pay attention to the results of one’s actions – to monitor the feedback… One of the basic differences between a person with an autotelic self and one without it is that the former knows that it is she who has chosen whatever goal she is pusuing. What she does is not random, nor is it the result of outside determining forces.

2. Becoming immersed in the activity

After choosing a system of action, a person with an autotelic personality grows deeply involved with whatever he is doing… To do so successfully one must learn to balance the opportunities for action with the skills one possesses… To achieve involvement with an action system, one must find a relatively close mesh between the demands of the environment and one’s capacity to act.

…

Involvement is greatly facilitated by the ability to concentrate. People who suffer from attentional disorders, who cannot keep their minds from wandering, always feel left out of the flow of life. They are at the mercy of whatever stray stimulus happens to flash by. To be distracted against one’s will is the surest sign that one is not in control.

3. Paying attention to what is happening

Concentration leads to involvement, which can only be maintained by constant inputs of attention.

…

Having an autotelic self implies the ability to sustain involvement. Self-consciousness, which is the most common source of distraction, is not a problem for such a person. Instead of worrying about how he is doing, how he looks from the outside, he is wholeheartedly committed to his goals.

4. Learning to enjoy immediate experience

The outcome of having an autotelic self… is that one can enjoy life even when objective circumstances are brutish and nasty. Being in control of the mind means that literally anything that happens can be a source of joy.

…

To achieve this control, however, requires determination and discipline. Optimal experience is not the result of a hedonistic, lotus-eating approach to life… [instead] one must develop skills that stretch capacities, that make one become more than what one is.

Conclusion

How does one go about starting to seek Flow activities? As Csikszentmihalyi quite rightly points out, it does not really matter where one starts, as you will end up at the same place:

The elements of the autotelic personality are related to one another by links of mutual causation. It does not matter where one starts – whether one chooses goals first, develops skills, cultivates the ability to concentrate, or gets rid of self-consciousness. One can start anywhere, because once the flow experience is in motion the other elements will be much easier to attain.

This will be a relief to educators, like me, who have control only over what goes on in their classroom. We can help make a difference! How?

- Build goal-setting and target-achieving into the work we do on a weekly basis. Make students feel the ‘buzz’ of having planned for, and achieved, something.

- Develop concentration skills. Build up students’ ability to focus on details for greater periods of time gradually over a series of lessons.

- Get students involved. Don’t let them just sit in the corner and be passive. Help them to play an active role in what goes on in your classroom. Involve them in their own learning!

- Share instances with students of when you have had to overcome adversity to achieve something. At a time when people are feeling down, give them something to be cheerful about. Model autotelic behaviour. 🙂

If that’s whetted your appetite, I’d encourage you to invest in the book and watch this video of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in action at the TED Conference (2004)

What are your views on Flow? Are you au fait with Csikszentmihalyi’s work? Add your views in the comments. 🙂

(Image by JasperVisser @ Flickr)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=82c64eb9-e463-42c0-a2ae-7ca85578baae)