TB872: Outstanding leadership and making the case for developing STiP

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

A 2010 research report by The Work Foundation entitled Exceeding Expectation: the principles of outstanding leadership outlined differences between good and outstanding leaders. For the purposes of this post, I’ve stuck to the executive summary (Tamkin, et al., 2010) which outlines three principles of outstanding leadership:

- They think and act systemically: they see things as a whole rather than compartmentalising. They connect the parts by a guiding sense of purpose. They understand how action follows reaction, how climate is bound and unravelled by acts, how mutual gains create loyalty and commitment, how confidence provides a springboard to motivation and creativity and how trust speeds interactions and enables people to take personal risks and succeed.

- They see people as the route to performance: they are deeply people and relationship centred rather than just people-oriented. They give significant amounts of time and focus to people. For good leaders, people are one group among many that need attention. For outstanding leaders, they are the only route to sustainable performance. They not only like and care about people, but have come to understand at a deep level that the capability and engagement of people is how they achieve exceptional performance

- They are self-confident without being arrogant: self-awareness is one of their fundamental attributes. They are highly motivated to achieve excellence and are focused on organisational outcomes, vision and purpose. But they understand they cannot create performance themselves. Rather, they are conduits to performance through their influence on others. The key tool they have to do this is not systems and processes, but themselves and the ways they interact with and impact on those around them. This sense of self is not ego-driven. It is to serve a goal, creating a combination of humility and self-confidence. This is why they watch themselves carefully and act consistently to achieve excellence through their interactions and through their embodiment of the leadership role.

Or, more briefly:

- Systemic thinking — outstanding leaders view organisations holistically, understanding the interconnectivity of components and actions. They create an environment of shared purpose, recognising how mutual gains and trust help motivation and creativity.

- Focus on people — outstanding leaders place the utmost importance on people and relationships as the key to sustainable performance. They invest a lot of time in nurturing team capabilities and engagement, recognising that people are central to achieving excellence.

- Appropriate self-confidence — outstanding leaders leaders balance self-confidence with humility, focusing on organisational goals while understanding their role as facilitators. This approach involves self-awareness and a commitment to influencing others positively, avoiding arrogance.

Thinking about my own career history, perhaps like most people I’ve had the misfortune of experiencing more poor and average leadership than good and outstanding. However, I can think of a couple of examples of outstanding leadership which would certainly back up these three points. In both cases, the people involved were understanding of the differences between the people they led, meaning that they had to help create an environment where all could flourish.

At the same time, in each case there was very much a ‘team’ ethos with an understanding of how we both related to one another and to the bigger picture. With one of the examples, the outstanding leader made us very aware of some of the politics involved and how they were representing and positioning us (as a team) in relation to this. I think that is a good example of systemic thinking.

A search of both the academic and popular literature around systems thinking in relation to leadership brings back a whole range of results. I was struck by the number of links to GOV.UK web page there were, which took me to a list of National Leadership Centre research publications. Of the 19 listed, eight mention ‘systems’ in the title, including one entitled Systems Leadership: How systems thinking enhances systems leadership by Catherine Hobbs and Gerald Midgley, both from the Centre for Systems Studies at the University of Hull.

The authors set the scene by talking about “systemic leadership” which they define as “systems leadership + systemic thinking” (Hobbs & Midgley, 2020, p.1). This is required because of the ‘wicked problems’ facing society:

Systems leadership views organisations as composed of interrelated parts, and it focuses on coordination of these parts to achieve a given purpose. When the issue being addressed is too complex for a single organisation to deal with alone, multiple organisations can become involved. Nevertheless, the idea is the same: constituent parts of an existing system must be ‘joined up’ into a greater whole.

(Hobbs & Midgley, 2020, p.1)

It’s a short paper at only four pages, but I was still surprised not to see any mention of anything resembling ‘B-ball’ and the role of the practitioner. Instead, a range of approaches is discussed with the focus on the importance of joined-up action. ‘System change’ here seems to be used systemically but the focus seems to be on changing the way (i.e. systematic) way that ‘delivery’ is done by public-sector bodies. Instead, argue the authors, we need an “exploratory, design-led, participative, facilitative, and

adaptive” future (Hobbs & Midgley, 2020, p.4).

Although I’ve never worked directly in government, as an informed (and often concerned) British citizen I have a keen interest in how it works. I’m also connected with a lot of people who work in various government departments. So I was interested to stumble across guidance on the GOV.UK site for civil servants entitled Systems Leadership Guide: how to be a systems leader. Although the word ‘systemic’ is mentioned six times in the overview, the approach outlined seems to be more systematic in nature.

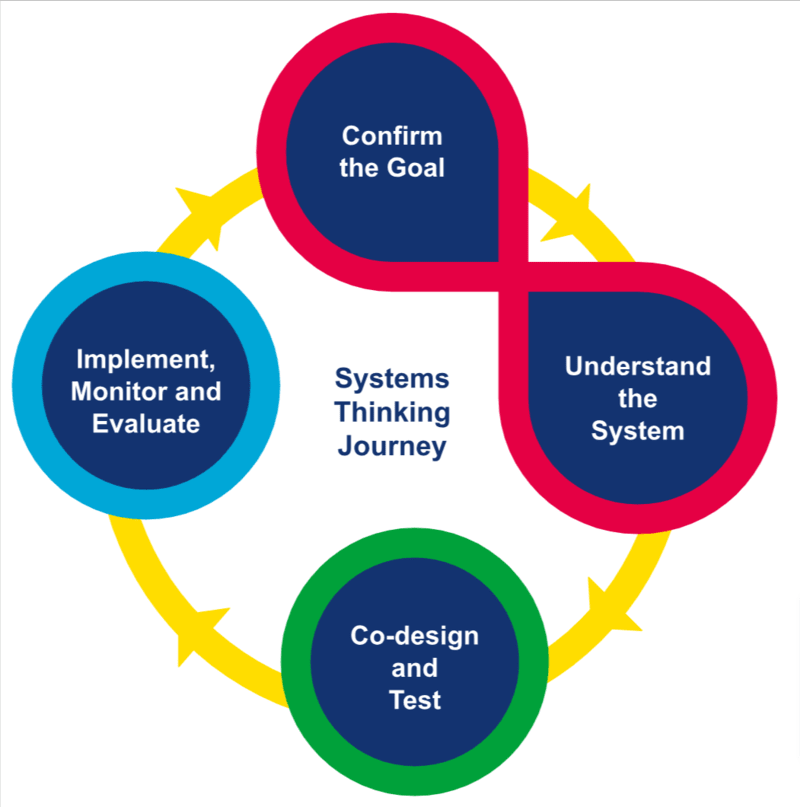

For example, the following diagram seems like quite a standard circular diagram that you would see on ‘leadership’ slides in every sector around the world:

The linked page, The civil servant’s systems thinking journey, goes into more detail with the above steps to make them feel less prescriptive. In addition, a systems thinking toolkit and systems thinking case study bank provide seem useful. What is still missing is discussion of the practitioner reflecting on their own ‘tradition of understanding’ and biases.

Although there is discussion of systems being both things you can see and things you can’t, the assumption still seems to be that systems are ‘out there’ in the world, and that systems thinking is an approach to increase performance or outcomes. It seems to be just another approach:

Systems thinking can be used alongside existing project management and stakeholder management techniques like Agile, P3M and Prince2 to strengthen them for dealing with complexity, uncertainty, multiple perspectives and broader interdependencies.

(The civil servant’s systems thinking journey, 2023)

The thought of using Prince2 alongside systemic approaches actually blows my mind.

One of the realisations I’ve had since starting this module is how pernicious the provision of pretty diagrams is. As with the GOV.UK example above, with systems thinking it’s problematic not to start with the individual practitioner reflecting on their own role in the world.

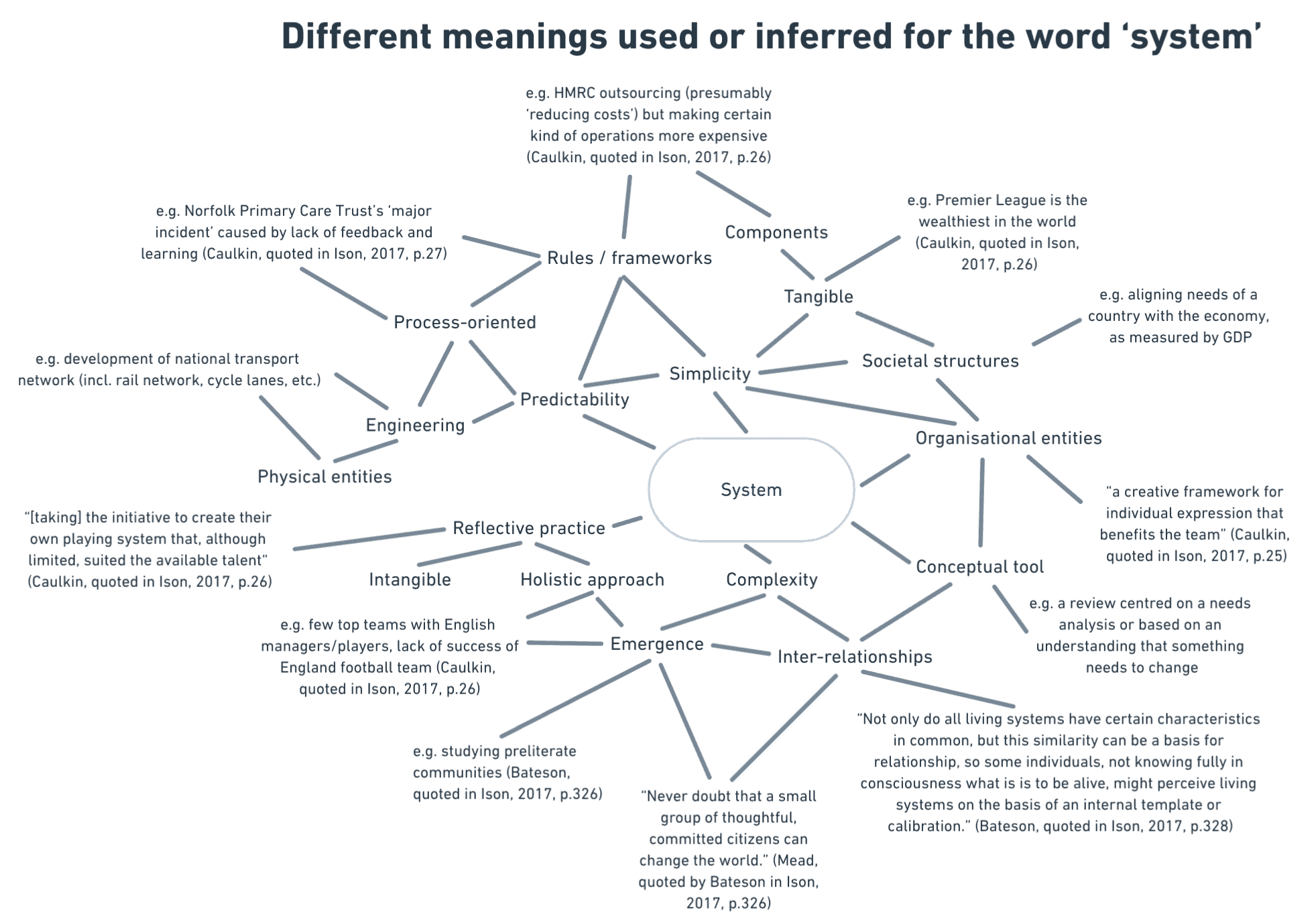

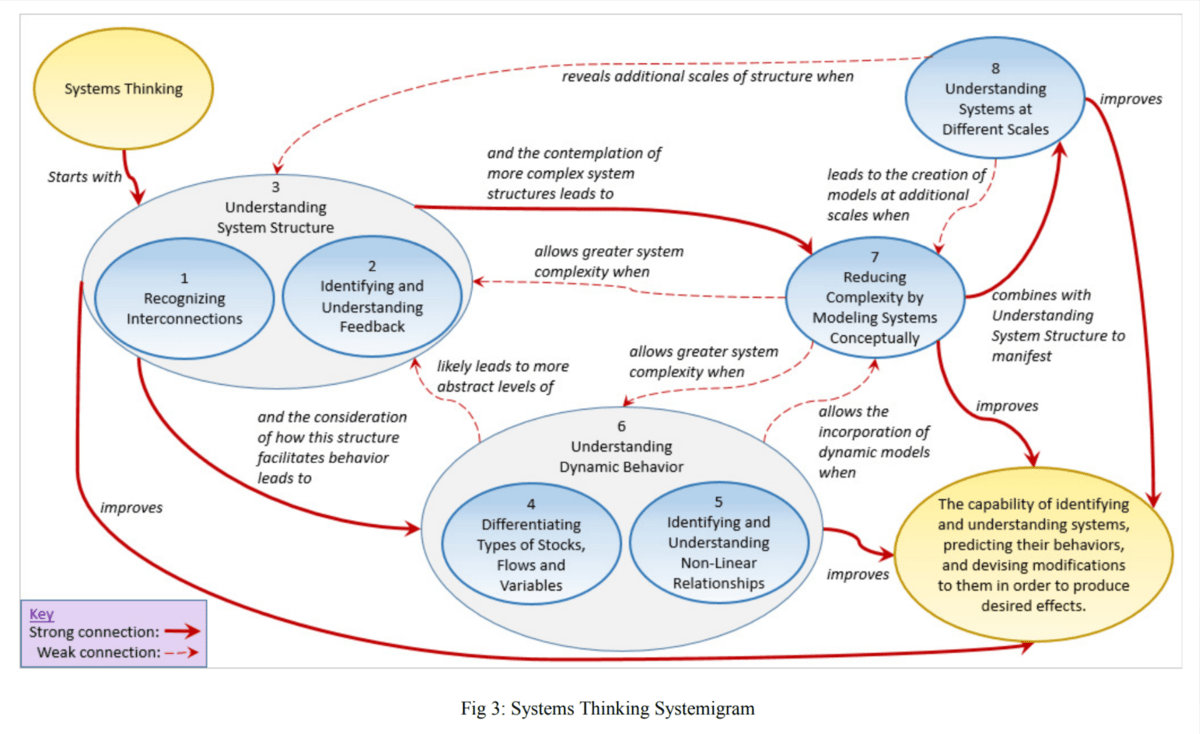

So how do we define what ‘systems thinking’ is. Can we use a systems thinking approach to define it? Now, given that I wrote my doctoral thesis explicitly trying to avoid ‘one definition to rule them all’, you’d expect me to appreciate an approach (Arnold & Wade, 2015) which uses a systemigram instead of simply presenting a contextless word-based definition.

Although potentially ‘scarier’ for those new to systems thinking (like me!) than the GOV.UK diagram, it’s so much richer.The resulting definition of systems thinking is: “The capability of identifying and understanding systems, predicting their behaviors, and devising modifications to them in order to produce desired effects.”

This may not be exactly the definition I would choose, but I appreciate being able to see how they arrived at it. It’s the kind of thing I’ve called for with frameworks for years. Just as with learning a new language, developing a systemic sensibility involves understanding what is and what is not useful when it comes to resources and discussion of systems practice.

References

- Arnold, R.D. and Wade, J.P. (2015) ‘A definition of systems thinking: a systems approach’, Procedia Computer Science, 44, pp. 669–678. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.03.050.

- Hobbs, C. and Midgley, G. (2020). How systems thinking enhances systems leadership. National Leadership Centre. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-leadership-centre-research-publications (Accessed: 29 January 2024).

- Systems Leadership Guide: how to be a systems leader (2023) GOV.UK. 12 January. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/systems-leadership-guide-for-civil-servants/systems-leadership-guide-how-to-be-a-systems-leader (Accessed: 29 January 2024).

- Tamkin, P., Pearson, G., Hirsh, W. and Constable, S. (2010). Exceeding Expectation: the principles of outstanding leadership. Work Foundation. Available at: https://www.bayes.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/117031/ExceedingExpectationexecsumm.pdf.pdf (Accessed: 29 January 2024).

- The civil servant’s systems thinking journey (2023) GOV.UK. 12 January. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/systems-thinking-for-civil-servants/journey (Accessed: 29 January 2024).

Image: DALL-E 3