On the paucity of our collective imagination. [Future of Education]

As happens quite often when I am exposed to something that helps transform my thinking or worldview, I’m not entirely sure how to get started with this one. So I’ll just dive straight in with a quotation:

The educational imagination of the last two decades has been dominated by one particular vision of the future, a vision of a global knowledge economy fuelled by international competition and sustained by digital networks. This vision has driven investment in new technologies, new approaches to teaching and learning, new education industries and massive school rebuilding programmes around the world. This vision has promised students and nations that with enough education, creativity and new technology, their futures will be secure. This vision of the future, however, can no longer be considered either robust or desirable enough to act as a reliable guide for education. (Keri Facer, Learning Futures)

Simon Bostock commented recently on my communitarian tendencies. He’s correct: I’ve recently co-kickstarted Purpos/ed and got involved with the PTA of the school my son attends. Civil Society is too important to be taken for granted: people are too busy gossiping and wasting their cognitive surplus:

Gossip is the opiate of the oppressed. (Erica Jong)

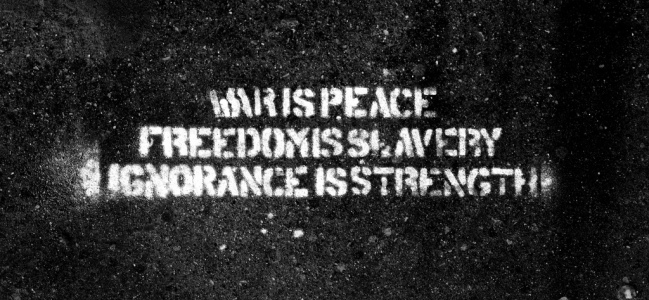

And we are oppressed. In fact, fairly often, we choose to be. Now that we’ve caught assassinated Osama Bin Laden, are we going to demand our rights back? Can we shut off those CCTV cameras please? Can we re-record those messages I hear in train stations threatening to destroy my unattended luggage? Will I be able to take a bottle of water on my next flight?

Thought not.

Stand up. Literally. Walk out of wherever you are right now – be it your home, your place of work, or your local library. Have a look around. Are we in danger? Really? I don’t want to live in a climate of fear and uncertainty – and nor do I want this to become normality for my children.

The biggest threat to our society isn’t terrorism: it’s our sense of community being slowly eroded by a creeping individualism. This individualism is hidden behind a mask of political correctness, of not wanting to cause ‘offence’ and through the tried-and-tested powers of advertising, fashion, and trend-setting. Where have the real thought-leaders gone? I’ll tell you. They’ve been lost in the quest for the perfect soundbite.

People like to be told what to do. Actually, that’s not entirely accurate. People like not to have to think. Does that sound controversial? It’s true. The majority of the population like to have established ways of doing things because of something that’s also true: we avoid conflict wherever possible. In doing so, we hand a voice to those who use conflict to increase their power and influence.

I’m generalising. Of course I am. You and I are different, aren’t we? Except we’re not. We’re slaves to the latest gadget, the latest news item and the views espoused by the latest celebrity. But more than that: we’re using tools of oppression to build futures for our children. We’re using rare earth minerals to fuel our obsession with gadgetry; we’re using forms of discourse that restrict our ways of conceptualising issues; and, most importantly of all, we’re propping-up outmoded education systems because of our belief that in doing so we’re helping our children.

As Keri Facer points out in the quotation I selected from her (excellent) new book, our vision of the future is no longer robust or desirable enough. We’re suffering from a paucity of collective imagination. We can’t even muster more than a sarcastic tweet or status update when a bunch of bankers wreck our entire economic system (and then pay themselves bonuses for doing so). We think it’s OK for blue-collar jobs, for call centres to be outsourced to the developing world, but what happens when the white-collar jobs go the same way? Are we prepared for that?

Is our education system adequate, relevant and proportionate? It’s not about campaigning for the latest technologies and an increase in ‘creativity’ in schools. Our problems go a whole lot deeper than that. These are difficult, knotty issues about social justice, the fabric of society and, ultimately, the human race. It’s time to do some real thinking and acting.

What are YOU going to do about it?

Image CC BY-NC-SA matthileo

What about these young people? http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-13465880 Maybe they are starting to think about new ways of resisting and initiating change.

I am currently reading Googled by Ken Auletta and one of the points he makes is that the issue is not what Google and their engineers do but how traditional business (fails to) responds to the changes brought about by what Google do. So change is not just wrought by those who initiate it but by the somnolence of the rest of us. One of the most satisfying parts of my job is supporting masters students from across the world in their development of critical engagement with information systems and technologies implemented in organisations and societies.

Perhaps we could reuse some of the ideas from this paper on conceptualising users of technology to find a different way of looking at how prospective learners and even societies can shape education even as they are shaped by it.

Thanks for the comment, Frances. :-)

I’m all for the type of demonstrations we’re seeing across Europe and the Middle East at the moment – the people are making themselves heard. The trouble is that it’s defined by being a response to hegemonic power, rather than a self-propelled movement investigating ways of building a more progressive Civil Society.

Would you say that the protests we’ve seen so far in 2011 have been the result of critical engagement?

I think it’s far too soon to say where these protests (and the Arab Spring) have come from or are going. Personally, I am just pleased to see any growth in political interest by young people.

In my purpos/ed post I said “Perhaps the purpose of education is to construct a participatory

dialogue about the purpose of education: a dialogue that makes a

difference to what learners experience throughout their lives.” Of course it goes beyond this to a participatory dialogue about the world we live e.g. political engagement.

I just realised that I failed to give the link to the paper http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&source=web&cd=1&sqi=2&ved=0CBgQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fciteseerx.ist.psu.edu%2Fviewdoc%2Fdownload%3Fdoi%3D10.1.1.106.7713%26rep%3Drep1%26type%3Dpdf&rct=j&q=wrong%20trousers%20robin%20williams&ei=M7PYTd-cCcjRhAfYv5HJBg&usg=AFQjCNGafueNFe1v7ZskK3SiAi6xGxbSzQ&cad=rja

Perhaps we could reuse some of the ideas from this paper on

conceptualising users of technology to find a different way of looking

at how prospective learners and even societies can shape education even

as they are shaped by it.

I keep saying this to you but you *really* need to read some Gramsci and the role ‘common sense’ plays in the maintenance of the current social order. He also provides a way of thinking about how to struggle against the forces you describe, especially through the means of education.

I know, I know – I’m just slightly put-off by the size of the ‘Gramsci

Reader’ I saw on your bookshelf once! I think this is all related to

the Overton Window: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overton_window