TB872: A virtuous circle of inquiry

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

One of the things I appreciate about this module is the way that it is scaffolded. New ideas and concepts are introduced incrementally, with prior learning referenced and reinforced.

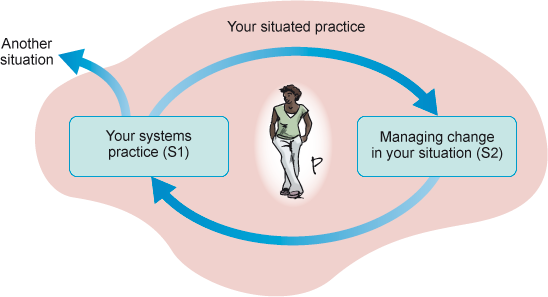

The above diagram introduced multiple systemic inquiries, S1 and S2. The former is my study and developing Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP), whereas the latter is a situation of concern that matters to me, and which I will focus on in my End of Module Assessment (EMA).

Simply put:

- Understanding my own practice (S1): I start by learning about my own way of thinking and working with systems. In other words, I get to know my own style and approach when handling complex problems.

- Applying what I’ve learned (S2): I use what I’ve learned about my style and approach to tackle a problem or situation. This is about putting my skills to work in the real world.

- Learn & improve: as I work on real-world problems, I’ll get better at understanding and applying STiP.

- Report & reflect: I’ll then write about what I’ve learned and how I’ve applied it. This is where I’ll show what I’ve done (and how I’ve understood what I’ve done).

- Keep going: the ‘virtuous cycle’ continues as a way of learning and solving problems (even after I complete TB872).

Initially, I was confused and assumed that S1 and S2 applied to ‘situation 1’ and ‘situation 2’. As they actually refer to ‘systemic inquiry 1’ and ‘systemic inquiry 2’ I guess it might have been clearer to refer to SI1 and SI2.

Over the next few weeks I’ll be defining S2 in more detail. Based on my learning contract, I should imagine it will be the project WAO is doing with the Digital Credentials Consortium (DCC). There is another project that could be interesting that we’re kicking off in the new year with Badgecraft and partners, but we won’t have held the stakeholder workshop before I’m due to submit my Tutor Marked Assessment 2 (TMA02).

In Ray Ison’s book Systems Practice: How to Act, Reading 5 (p.172-182) explains how he managed to carry out a systemic inquiry which resulted in changing modes of thinking among UK organisations involved with agriculture. As I’ve experienced before, it can be very frustrating working with people who either bring you in to tell you what they already know, to bolster something they’ve already decided they want to do, or to act as a scapegoat should a project fail.

In this situation, Ison was being brought in to advise on a knowledge transfer strategy (KTS) which seemed set up to fail. Not only had previous KTS initiatives failed, but communication was seen as ‘signal transfer’, and the focus was on changing other people’s behaviour. What was interesting to me was the way that Ison flipped the script to “build an invitation upon an invitation”. He conducted short one-to-one interviews in an initial stakeholder meeting, followed by a meeting bringing together all of the interviewees. He then used a spray diagram to show what he’d learned.

Even more interesting was the fact that Ison focused on the metaphors, both implicit and explicit, that interviewees used to describe what was going on:

Metaphors provide both a way to understand our understandings and how language is used. Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we think and act, is metaphorical in nature. Paying attention to metaphors-in-use is one means by which we can reflect on our own traditions of understanding. Our models of understanding grow out of traditions, where a tradition is a network of prejudices that provide possible answers and strategies for action. The word prejudices may be literally understood as pre-understanding, so another way of defining tradition could be as a network of pre-understandings. Traditions are not only ways to see and act but a way to conceal (Russell and Ison 2000a).

Ison, R. (2017) Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

By showing that the metaphors that people use are problematic, are based on outdated approaches, or are in conflict with other stakeholders, a space is opened up for discussion. This can be a small ‘chink’ of light in what is otherwise a command-and-controlled, information-as-dissemination environment. From there, Ison managed to separate the ‘what’ needed to be done from the ‘how’ — which, he notes, was “something that I sensed had not occurred to those present”.

Ison suggested that a systemic inquiry, based on some design criteria, would be a good place to start. From this point on, he perceived a shift in the language used to be more participatory. Of course, the claim was that this more participatory approach had already started before Ison became involved but that the language used “had not yet caught up”. People are easily embarrassed, I guess, and try to cover their tracks.

Context is extremely important. It’s the reason that people behave as they do in certain situations and not in others. For example, it’s the reason why you might get told off for swearing in front of kids but not in front of adults. The trouble is that we assume a shared context when people might actually be having very different experiences. For example, you may be forgiven if it transpires that you had just accidentally hit your thumb with a hammer.

The first thing to establish when working with other people is therefore what the shared context might be. If there is a lot of conflict or misunderstanding, it’s likely that there is a lack of shared context, and that people are ‘talking past one another’ as their mental models differ. This can even happen when people are using the same words or terms, as they are dead metaphors.

Take, for example, the word ‘sustainability’ which is used very differently depending on the specific context. From an environmental perspective, sustainability usually refers to ecological balance, so environmentalists might focus on preserving ecosystems, biodiversity, and reducing pollution. In a business context, however, sustainability usually means financial viability and long-term profitability, so business leaders might focus on creating business models that can withstand market fluctuations and economic downturns. And then, from a social point of view, sustainability is often about creating equitable and inclusive communities, so sociologists might focus on social justice, equal access to resources, and supporting marginalised groups.

As you can imagine, bringing environmentalists, business leaders, and sociologists together can mean that they could be using the same word quite differently. This is something for me to bear in mind when thinking about my S2, my real-world systemic inquiry.

Ever since being involved with eye-opening user research as part of a project I led during the pandemic, we’ve included it wherever possible in our work through the co-op. In fact, with the DCC work we kicked off recently, which is ostensibly about documentation, asset creation, and storytelling, we began with a first round of interviews with staff. We’ll be widening this out to a second round of interviews with other stakeholder groups in the new year.

What’s interesting about this is that we’ve already found a slight discrepancy between the implicit theory of change coming from reports that the DCC put out, and that which emerged from user research interviews. This provides the ‘chink’ mentioned above, the space to start thinking about design criteria and think about what we’re doing as “a system to (X)” rather than simply a project.