TB872: Projectification and an apartheid of the emotions

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

At the start of Chapter 9 of Ray Ison’s book Systems Practice: How to Act, he outlines “four contemporary settings that constrain the emergence of systems practice”:

- The pervasive target mentality that has arisen in many countries and contexts

- Living in a ‘projectified world’

- ‘Situation framing’ failure

- An apartheid of the emotions

The chapter really put into words for me something I’ve felt throughout my career around targets, projects, and the (supposed) benefits of an ultra-rationalistic approach.

My argument put simply is that the proliferation of targets and the project as social technologies (or institutional arrangements) undermines our collective ability to engage with uncertainty and manage our own co-evolutionary dynamic with the biosphere and with each other. This is exacerbated by an institutionalised failure to realise that we have choices that can be made as to how to frame situations. And that the framing choices we make, or do not make, have consequences. In doing what we do we are also constrained by the institutionalisation of an intellectual apartheid in which appreciation and understanding of the emotions is cut off from practical action and daily discourse.

Ison, R. (2017) Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. p.225. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

To some extent, this links to my voodoo categorisation post, something I discussed as a guest on a recent podcast episode. In that case, the ‘voodoo’ comes from the assumption that creating an ontology and then manipulating it will make a change in the ‘real world’. With Ison’s framing, the ‘voodoo’ comes from targets (e.g. KPIs) which are the results of projects. Without reference to humans as social, emotional animals, nor to the way a situation is framed making a difference both to the start and the end point, real harm can be (and often is) done.

This is probably another good place to embed Prof. Stein Ringen’s RSA talk about systemic failures in UK governance:

Change doesn’t happen just because someone has a cool idea or an organisation has some money to spend. Real change, to quote Monty Python and the Holy Grail, comes from a mandate from the masses. In this case, stakeholder and user buy-in, based on shared understandings and an acknowledgement of relationships and emotions.

Ison points out that government ministers and bureaucrats often use the term ‘systemic failure’ to wash their hands of responsibility. As he says, without being able to explain how the systemic failure came to happen, it’s a subtle way of distancing themselves from their participation in the system.

He cites a 2009 article by Simon Caulkin in The Guardian, which has helped me realise just how problematic targets in large organisations can be:

Target-driven organisations are institutionally witless because they face the wrong way: towards ministers and target-setters, not customers or citizens. Accusing them of neglecting customers to focus on targets, as a report on Network Rail did just two weeks ago, is like berating cats for eating small birds. That’s what they do. Just as inevitable is the spawning of ballooning bureaucracies to track performance and report it to inspectorates that administer what feels to teachers, doctors and social workers increasingly like a reign of fear.

If people experience services run on these lines as fragmented, bureaucratic and impersonal, that’s not surprising, since that’s what they are set up to be. Paul Hodgkin, the Sheffield GP who created NHS feedback website Patient Opinion… notes that the health service has been engineered to deliver abstract meta-goals such as four-hour waiting times in A&E and halving MRSA – which it does, sort of – but not individual care, which is what people actually experience. Consequently, even when targets are met, citizens detect no improvement. Hence the desperate and depressing ministerial calls for, in effect, new targets to make NHS staff show compassion and teachers teach interesting lessons.

What’s doubly-interesting is that my sister works for Care Opinion (which is the new name for Patient Opinion). I shall be discussing this with her!

In my own career, I’ve seen as a teacher how promises made by government ministers filter down and become an extra tick box on a scheme of work. I’ve seen in tech organisations how the introduction of OKRs mean that people spend less time actually getting anything done. And, as a consultant, I’ve seen plenty of examples of organisations who are more interested in hitting targets so their board gives them less of a tough time, rather than actually serving their audience.

Why are targets so problematic? Ison lists three reasons:

- Targets often lack flexibility and don’t adapt well to changing circumstances.

- Creating targets is easy, but monitoring and enforcing them is challenging and costly, often only revealing their effectiveness after a failure occurs.

- Targets can hinder the creation of locally tailored solutions and more effective performance indicators specific to a particular situation, issue, or concern.

He suggests that often, especially in the case of governments, targets are performative: “we’ve got a target for it, so we must be doing something about it!”. It’s hard not to think of the Tory rhetoric around ‘StOp ThE bOaTs’ which is essentially government by campaign leaflet. In my own life, it’s the never-ending call to “teach this stuff in school” — especially if it’s the kind of thing that was previously instilled by parents or society, or is new and scary.

Moving onto projects, Ison talks about how pervasive they are. Kids start with projects at school, and then we seemingly never stop with them until we die. Even football managers talk about their jobs as ‘projects’ these days, and entice players who are “excited by the project“.

As soon as you think about it, it becomes patently obvious that we live in a projectified world. I can hardly remember a time when a project was not part of what I did – whether at school or throughout my professional life. The word project has its origins in the Latin projectum, ‘something thrown forth’ from which the current meaning of a plan, draft or scheme arises. It would seem that the meaning, now common across the world, of a project as a special assignment carried out by a person, initially a student, but now almost anyone, is first recorded in 1916 (Barnhart 2001). From that beginning I am not really sure how we came to live with projects in the manner that led Simon Bell and Stephen Morse (Bell and Morse 2005) to speak of a ‘projectified-world order’. Perhaps mass education carried forth the project into all walks of life? Whatever this history, my experience suggests it is no longer tenable in a climate changing world to have almost all that we do ‘framed’ by our invention of ‘the project’.

Ison, ibid. pp.230-231

The difference between concept and reality is, for me, exemplified by thinking about Open Source Software projects (OSS). These exist to bring forth something useful in the world, software that people can use — even if it’s only the programmer themselves. However, if we zoom out and think about OSS as an ecosystem, we can see projects begin, fail, adapt, succeed, morph into new things, etc. In this way, it’s almost appropriate to use a biological metaphor.

In my view of the world, which is broadly informed by Pragmatism, everything is a bridge to something else. A project, therefore, does not really have a defined start or end, but is perhaps better thought of as an intervention in a given system. One needs to understand the system before trying to intervene. This is somewhat at odds with ‘project management’.

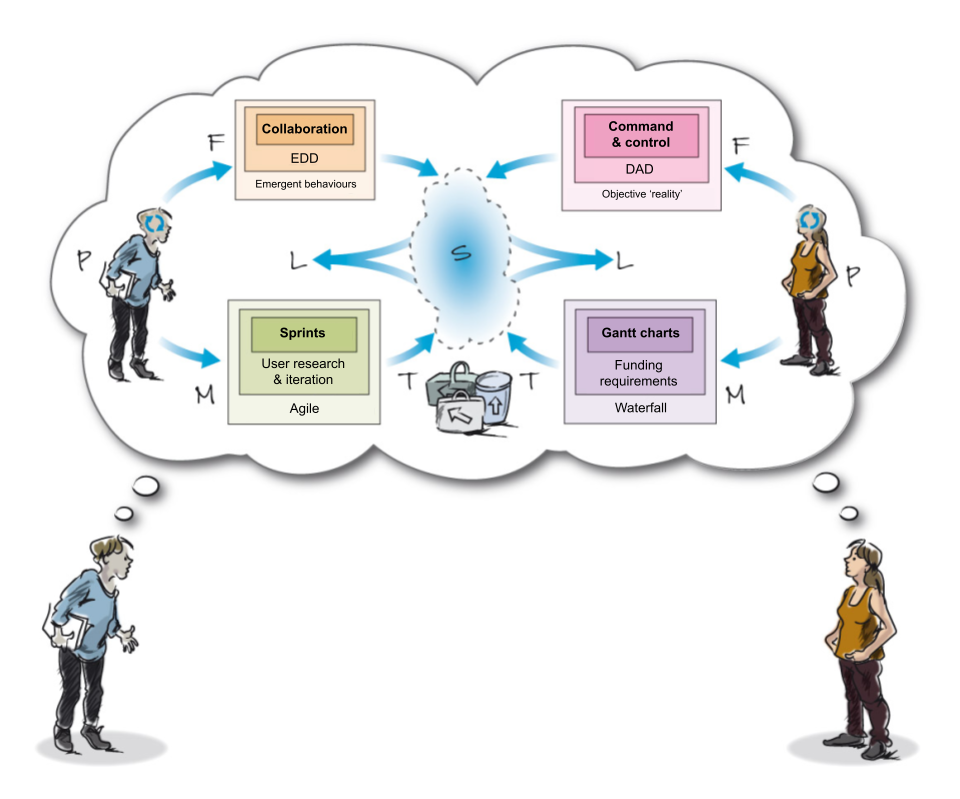

Ison discusses the PRINCE2 methodology, which I’ve had the misfortune of having to study. I got a passing grade, but I disagreed with the approach with every fibre of my being.

The understandings on which PRINCE-type methods are built perpetuate and reproduce practices that privilege a ‘technical rationality’… In other words we have arrived at a point where those who do project managing are not fully aware of what they do when they do what they do! Ironically this is largely due to the reification or projectification of project management itself. This has major implications for governance and, ultimately, how we respond in a climate-changing world.

Ison, ibid. p.234

Amen to that.

One of the things I very much appreciate is the ability to bring my full self to work. I am, as anyone who knows me well will testify, a sheep in wolf’s clothing, a velvet fist in an iron glove. (By this I mean to reverse the usual metaphors and suggest that I’m hard on the outside but soft on the inside.) I get upset easily. I get angry easily. These are all things that I’ve worked on all of the years, but fundamentally emotion is what makes us human.

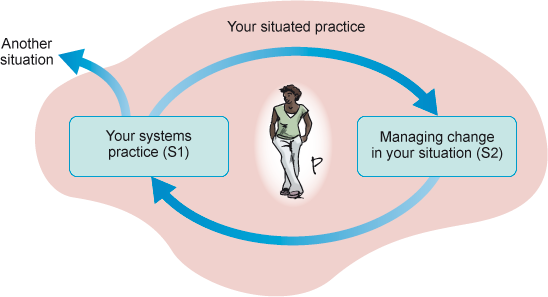

To try and ignore emotion when working with other humans is therefore emotionally unintelligent. It’s a denial of a fundamental part of the PFMS heuristic.

Following Maturana et al. (2008) emotioning is a process that takes place in a relational flow. This involves both behaviour and a body with a responsive physiology that enables changing behaviour. Thus, ‘a change of emotion is a change of body, including the brain. Through different emotions human and non-human animals become different beings, beings that see differently, hear differently, move and act differently. In particular, we human beings become different rational beings, and we think, reason, and reflect differently as our emotions change’. Maturana et al. (2008) explain that humans move in the drift of our living following a path guided by our emotions. ‘As we interact our emotions change; as we talk our emotions change; as we reflect our emotions change; as we act our emotions change; as we think our emotions change; as we emotion… our emotions change. Moreover, as our emotions constitute the grounding of all our doings they guide our living’.

Ison, ibid. p.242

I agree that we should not be subject to our emotions, nor should we make policy solely on the strength of feeling. Yet there are ways to be emotionally intelligent and allow emotions to play a role within systems thinking. For example, Ison talks of Barack Obama and his capacity for listening, his encountering other people as ‘legitimate others’, his technique of ‘mirroring back’ the position of others, the ability to move between different levels of abstraction, and his awareness that change comes through relationships.

Ison talks of a “choreography of the emotions” and compares and contrasts this choreography (“one practised in the design of a dance arrangement”) with chorography (“one practised in the experiencing of territory, or situations”). One role therefore involves understanding different situations, like someone who explores new places, whereas the other role is about planning and organising actions, like a dance director arranges a performance.

Both chorography and choreography includes figuring out how emotions lead to certain results and looking at how long-standing patterns of behaviour develop in places like work or in personal life. Part of their job is to keep planning and adjusting how people communicate and act, which is both a creative and important task. They focus on managing emotions because they believe that our feelings and desires are what really drive our actions, more than the tools or resources we have.

Too often change is understood systematically rather than systemically. From a systemic perspective change takes place in a relational space, or dynamic, including the space of one’s relationship with oneself (i.e. through personal reflection). Russell and Ison (2004, 2005) have argued that it is a shift in our conversation and the underlying emotional dynamics that more than anything else brings about change in human social systems.

Ison, ibid. p.246

Particularly in this time of climate crisis, we need new and more joined up ways of thinking and acting. An understanding that projects and targets aren’t going to save the world will help. As will framing the situation in a way that promotes a shared (urgent) understanding. But, in my opinion, more than anything, it’s the emotional aspect that will make the difference. After all, as Jonathan Swift may or may not have said, you cannot reason someone out of a position they didn’t reason themselves into.

Image: DALL-E 3