TB872: Systems, situations, and systemic praxis

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

11 years ago I gave a TEDx talk on digital literacies. Around the 12 minute mark, I mentioned that it’s useful to consider literacies as developing in terms of ‘progressive encoding’ rather than ‘sequential encoding’. This is a bit of a geeky analogy from the early days of internet when images could take a while to download.

In other words, as the slide below shows, the development of literacies happens by progressively adding detail to our understanding. It is not best developed through a course where (to use a gaming analogy) a ‘fog of war’ prevents you from knowing what comes next.

I mention this as at the start of Chapter 2 of Systems Practice: How to Act by Ray Ison, he talks about how people move from having a systemic sensibility, through to having a form of systems literacy, and then on to systems thinking in practice (STiP) capability. I see this spectrum as being similar to the holistic approach I was advocating for in that TEDx talk.

Engaging with Systems is perhaps like learning a new language — I could refer to it as learning ‘systems talking’, where ‘talking’ involves thinking and doing, i.e. practice. It is the sort of learning that can challenge our sense of identity. It is as if ‘systems talk’ is ‘talk that undermines the boundaries between our categories of things in the world, [and thus] undermines “us,” the stability of the kinds of beings we take ourselves to be.’

Ison, R. (2017) Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. pp.19-20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

If systems thinking is like learning a new language, then it can be challenging to talk using a new vocabulary and grammar to people who do not understand it. Ison gives words to something I’ve come up against in my work; it can seem ‘reasonable’ to want evidence and examples and proof but… the world doesn’t work like that?

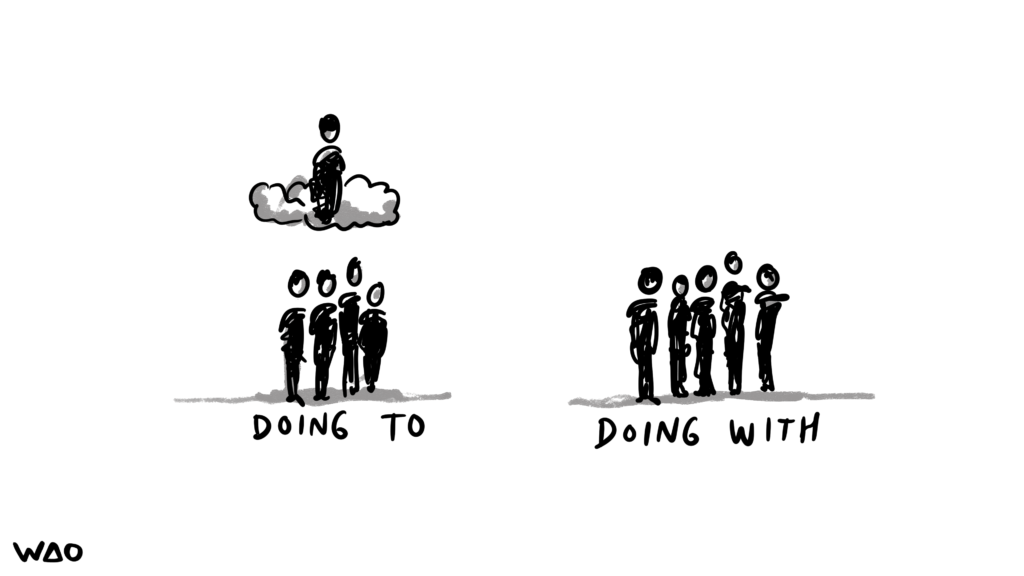

Those who do not think systemically usually require explanations of what ‘it’ is and justification or evidence that ‘it works’ or that there is a ‘value proposition’ for engaging with it. There is also a tendency to require explanations of effectiveness in causal terms of the form: ‘using systems thinking can cause X to happen’ i.e., using a framework of linear causality in which a systemic view is lost because one cannot understand circularity by making it linear.

Ison, R. ibid. p.20.

I totally get having a ‘theory of change’ and working backwards from a desired future state. But to require evidence that a new approach will work, or that one that has worked elsewhere will work in a different context, is to essentially ask us to get out a crystal ball. As Ison notes, it’s an attempt to turn something holistic and systemic into something which is linear and systematic.

One of the things that a background in Philosophy allows you to do, I think, is to be more comfortable with ambiguity. Or it may be simply that my own studies have led to me being interested in, and therefore more comfortable with it. Either way, Ison believe ‘abandoning certainty’ to be a good way to provide the conditions to start thinking and acting systemically (Ison, ibid. p.21). He also talks about being ‘open to your circumstances’ which I’ve discussed elsewhere as cultivating a larger serendipity surface.

The interesting thing here is that, while the world (and especially the corporate world) is set up to remove emotion from our working environments as much as possible, abandoning certainty and being open to your circumstances requires an emotional response. To use a flamboyant metaphor: instead of trying to reduce us to a monochrome grey, it allows us to interact with one another’s rainbow colours.

I have a lot in common with what I’ve read of Ison’s work. For example, he refuses to give a definition of systems thinking or systems practice. In my doctoral thesis and subsequent ebook, I did likewise, calling for people to come up with their own definitions based on eight essential elements of digital literacies I identified.

In my experience definitions are constraining because (1) they are abstractions and thus a limited one dimensional snapshot of a complicated dynamic and (2) we do not appreciate how definitions blind us to what we do when we employ a definition.

Ison, R. ibid. p.22.

As a Pragmatist, I’m not so against definitions as Ison seems to be, as I think they can be ‘useful in the way of belief’ for a community of inquirers. In fact, I’d argue that the discussion that leads to the definition is what’s important. The trouble comes when a definition becomes what Richard Rorty would call a ‘dead metaphor’, no longer doing any work. That’s why we need to continually return to and reassess our assumptions, using the Sigmoid Curve.

To relate another concept of Ison’s to my own work, in a footnote on p.25 he quotes John Shotter (1993) as saying “why do we fell that our language works primarily by us using it accurately to represent and refer to things and states of affairs in the circumstances surrounding us, rather than by using it to influence each other’s and our own behaviour?” I see this as similar to my discussion of voodoo categorisation based on the work of Clay Shirky. We create a model that (we believe to) perfectly represent the world, says Shirky, then manipulate the model and are surprised when the world does not change as a result.

I don’t often read books in any way other than from start to finish, but Ison, as the author of this book, has instructed us to read this one in a bit of a topsy-turvy way. For example, I’ve already read Chapter 9, 10, and 13, and now I’m on Chapter 2.

As a result, I’ve come across concepts and phrases for which I haven’t had a clear definition. I was therefore pleased, to come across this explanation of the link between systems thinking and practice:

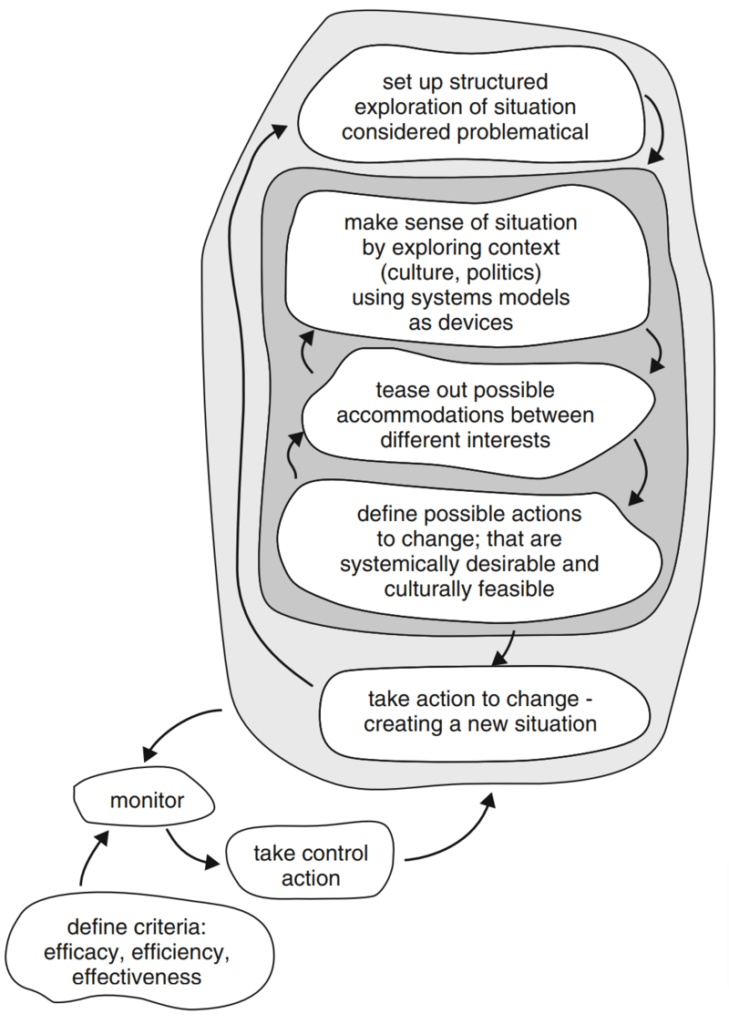

The terms systems thinking and systems practice are different ways of being in the same situation. This can be understood as a recursive dynamic much like the relationship between the chicken and egg — they are linked recursively and bring each other forth — speaking metaphorically they can be seen as mirror images of each other. Understood as a recursive dynamic systems thinking and practice can also be described as systems praxis — theory informed practical action.

Ison, R. ibid. p.30.

Doing systems thinking with systems practice is a bit like spending time coming up with a privacy policy and then not acting in a way which would be in accordance with it. In other words, it’s useful, but it’s not praxis; it makes little difference to the world.

Finally, as I come to the end of Chapter 2, what is the difference between a ‘situation’ and a ‘system’?

A situation is the context in which things happen. A real-world setting such as an office, or a family household, or a natural habitat. Situations are usually complex, messy, and characterised by both uncertainty and multiple perspectives. For example, the boss has a different perspective to the cleaner; the parent has a different perspective to the child; the biologist has a different perspective to the economist. Situations are the starting point for any STiP process.

A system, on the other hand, is a construct, a mental model used to make sense of some aspects of a situation. It’s an abstract representation which helps us understand the situation’s dynamics, for example by identifying patterns, structures, and behaviours that might not be immediately apparent. For example, a system might be a company’s project management system, or a family’s meal planning system (including recipes, shopping lists, cooking rota, budgets, etc.), or a wildlife monitoring and management system (including methods for tracking animal populations, habitats, the impact of human activities, conservation strategies, etc.)

So the situation represents the broader context with all its complexities and dynamics, while the system represents a more focused, structured approach to understanding and managing specific aspects of that situation.