TB872: Situations of concern, systems of interest, and PQR statements

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

I’ve already pointed out in this module how difficult it can be when there are two words which are often used in a similar situation that look or sound the same. So, for example systemic (something that relates to, or affects, an entire system as a whole, rather than just its individual parts) and systematic (a process or method that is done according to a fixed plan or system).

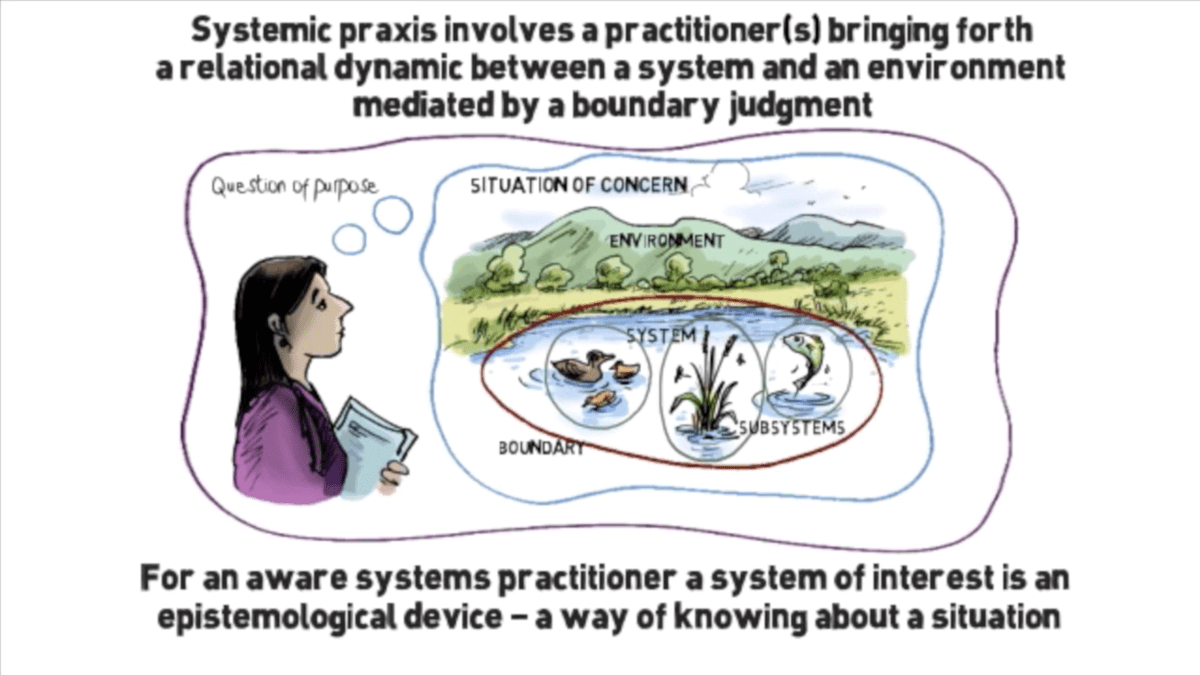

Only slightly less confusing, until you get your head around it is the difference between a situation of concern and a system of interest. I thought the best way to illustrate it might be to come up with my own example, rather than use the one in the course materials. So let’s talk about football (soccer).

In the last decade, Video Assistant Referees (VAR) have become an increasingly large part of the professional game. This has had a huge impact on the sport: it’s changed the way matches are officiated, the way players interact with referees (and one another), and even affected how long spectators need to allow for getting home at the end of a game, as they often massively ‘overrun’.

Let’s imagine a football coach whose team has won promotion from the Championship (no VAR) to the Premier League (VAR). From pre-season training onwards, while VAR has always been part of the coach’s situation of concern, it’s now part of their system of interest. That is to say, whereas previously it might have only affected the sport that he coaches more generally, and perhaps the occasional cup game that the team he coaches plays in, now he needs to prepare for VAR being a factor in most matches.

That means the coach needs to understand the intricacies of VAR, choose and apply relevant frameworks (e.g. adapting team strategies), and make explicit choices and changes. This might even involve the recommendation of buying new players, or training in a different way. An example of the latter would be that if a game is likely to be more stop-start and players are likely to be out on the pitch for, say, 105 minutes instead of 90 minutes, then they should be prepared for this.

To summarise, then, the coach is a practitioner whose situation of concern (the world of football) has changed in a way directly related to their system of interest (the team they coach).

Thinking about module TB872 as a system of interest to me, as a practitioner, this brings us to the Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) of thinkers like Peter Checkland. SSM is a useful methodology when dealing with situations where there are significant social, political, and other ‘human’ components. It does not assume that there is a single, objective ‘problem’ to be solved, but rather recognises that there are many different perceptions of problems. It therefore offers a structured approach to explore these differing perceptions among stakeholders.

We’re not going into too much detail around SSM right now, just looking at what are called PQR statements. These take the following format:

A system to do P (what) by Q (how) because of R (why).

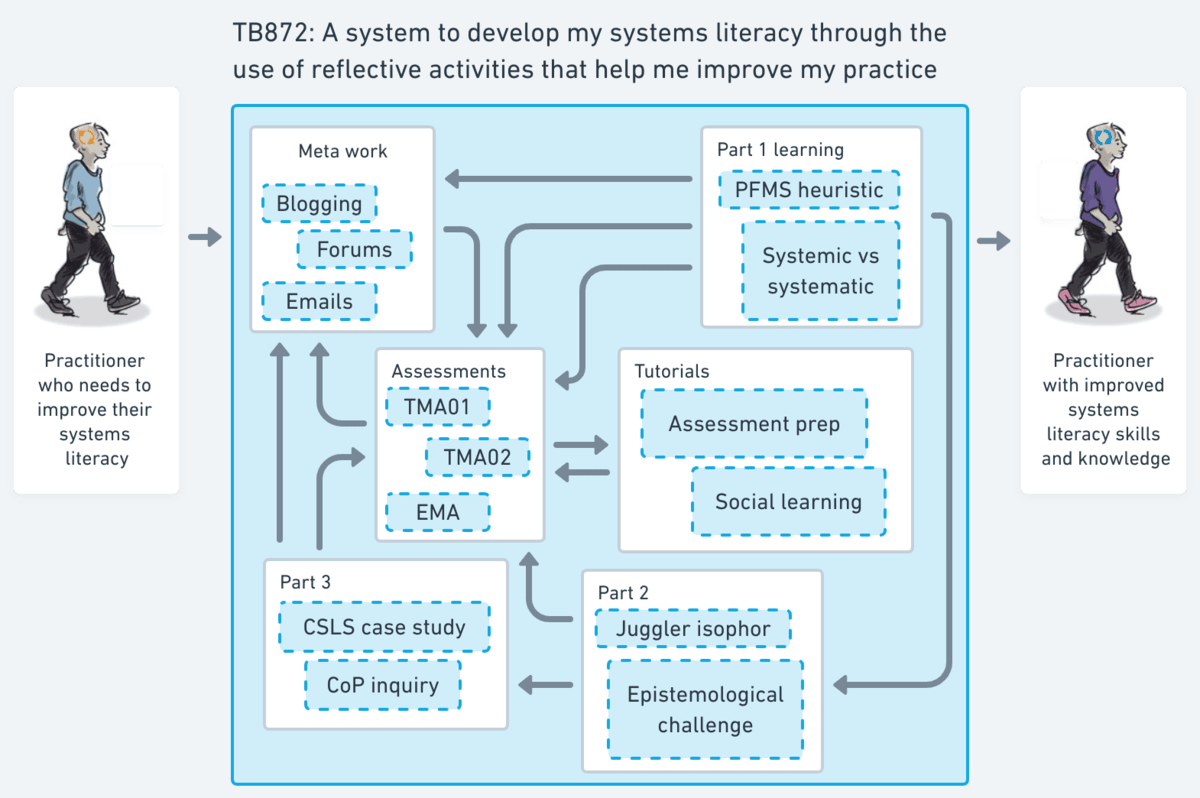

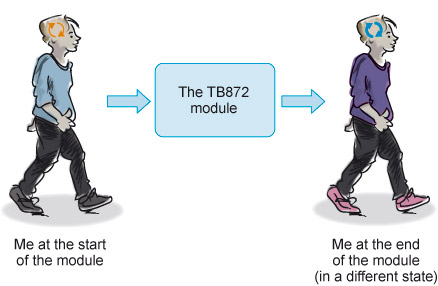

As the course materials note, the simplest way of referring to the ‘change’ that occurs in us as practitioners because of our involvement in the TB872 as students is represented in this diagram:

The interesting thing, of course, is what’s in the box. Representing it using a PQR statement from my own perspective might yield:

A system to develop my systems literacy by helping me reflect and complete activities about Systems Thinking because of a need to improve my practice.

It’s a bit of a clunky statement, so the concise version is probably: “A system to develop my systems literacy through the use of reflective activities that help me improve my practice”.

Thinking about that ‘black box’, this is a brief and cursory overview of what’s inside it, from my point of view:

As the course materials state, everyone’s diagrams will be slightly different. I noticed that the module authors’ focused very much on the way that the module is organised rather than on the way it is experienced, for example. This is something I would go into a bit more, if it wasn’t for the fact that I’m rushing to get this done on a weekend inbetween driving my kids between sporting activities and social engagements!

To conclude, then, the system of interest for me is shown above in the diagram I have drawn. This sits within a wider situation of concern, which could be thought of as being my whole MSc, or (given that I’ve already referred to my family) my life as a husband and parent. A systems diagram like this is to show in a visual way systematically desirable change from a particular point of view. I always find visual aids useful when talking to others and helping them explain a point of view, and so getting better at these will help my practice no end.

Top image: DALL-E 3