TB871: Bricolage, rigour, and service design

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

It’s been over a decade since I started wondering out loud about whether people really knew what they were talking about when they use the term ‘rigour’. In that particular case, it was whether then UK Education Secretary Michael Gove knew what he was talking about:

What concerns me about Gove’s proposals is the assumption that rigour consists of a very particular method of assessing young people’s knowledge, understanding and skills. I say this as a former teacher and senior leader, as someone who is currently involved in education on a national and international level and, most importantly, a parent. The ability to sit still and concentrate for three hours on examination questions testing feats of memory does not sound to me like a 21st century skill. Which pieces of the complex puzzle of human knowledge, skills and understanding are not captured under such a system? I’d suggest many.

(Belshaw, 2012)

I was reminded of this as I come to work on Activity 1.18 of this module, which introduces the module author’s (Martin Reynolds) views on rigour:

Disciplinary rigour is usually measured by a sense of reliability in the disciplinary tools used. Replicability of tools used in the same way across different situations or for specific situations is usually a good guarantor for reliability. I have argued that relying on one guarantor for rigour might be restrictive, and can lead to a sense of rigor mortis (Reynolds, 2015). For a transdisciplinary area of practice like STiP or evaluation, it is important to have several co-guarantor attributes. In the article (Reynolds 2015) I flag three sets of co-guarantor attributes (CoGs) – reliability/replicability, resonance, and relevance – each interrelated and conforming respectively with the three entities of the STiP heuristic.

(The Open University, 2020)

Reynolds introduces the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss around bricolage, which is a concept referring to a process of improvisation and creativity. Individuals (or organisations) make use of whatever resources they have on-hand to solve problems. The term comes from the French word bricoler which means ‘to tinker’.

Karl Weick leant on the work of Lévi-Strauss in an article entitled ‘Organizing for High Reliability’ (Weick, et al., 1997) and Reynolds presents and expands on Weick’s four attributes of a successful bricolage:

(The Open University, 2020)

- Careful observation and listening – incorporating the idea of conversation; the bricoleur works with others in the village where s/he visits.

- Intimate knowledge of resources – each situation is different with different resources, human and non-human; the bricoleur must be adaptable to the resourcefulness of the situation at hand.

- Trusting one’s own ideas – whilst situations vary and are always in a state of flux, the bricoloeur remains self–confident, though not arrogant, in the tools and experiences gained.

- Self-correcting structures with feedback – bricolage is adaptable to change, accepting a safe-fail environment which allows for errors and experimentation, but embraces the learning emerging from such situations.

For example, new tech startups which might have a lot of talent at their disposal but not much cash might use Agile development methodologies, combined with a range of Open Source technologies, rapidly iterating their product. Or healthcare practices in rural, resource-constrained environments might lead to the development of medical devices that operate without electricity. Likewise, urban gardeners often make do with what is available, perhaps turning an abandoned area into a community garden using recycled materials and local knowledge.

In their paper ‘A bricolage perspective on service innovation’ (Witell, et al., 2017) the authors present an approach to bricolage which aligns well with Reynolds’ three co-guarantor attributes (CoGs) of reliability, resonance, and relevance. The table below, created with the help of GPT-4, outlines the overlap:

| Bricolage Aspects (Witell et al.) | Bricolage Capabilities | Co-Guarantor Attributes (Reynolds) | Description of Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Making Do with What is Available | Using available resources creatively. | CoG1: Reliability | Both emphasise the use of existing tools and resources in a consistent and adaptable manner. The bricolage principle of ‘making do’ aligns with replicable methods of resource application. |

| CoG2: Resonance | Making do ensures solutions are contextually appropriate, providing resonance with the immediate environment and its challenges. | ||

| CoG3: Relevance | By focusing on available resources, solutions are directly tailored to meet current needs, ensuring relevance. | ||

| Improvising When Recombining Resources | Adapting and combining resources in new ways. | CoG1: Reliability | Improvisation in bricolage demonstrates a reliable approach to innovation under constraints, maintaining methodological consistency. |

| CoG2: Resonance | Improvisation ensures that solutions resonate with stakeholders by adapting to feedback and changing needs dynamically. | ||

| CoG3: Relevance | Improvised solutions maintain relevance by adjusting to real-time feedback and evolving challenges. | ||

| Networking with External Partners | Collaborating and utilising external insights. | CoG2: Resonance | Networking enhances resonance by ensuring solutions are developed in collaboration with stakeholders and reflect shared insights. |

| CoG3: Relevance | Networking keeps solutions relevant by incorporating diverse perspectives and resources from a broader community. | ||

| Careful Observation and Listening | Engaging with the context and stakeholders. | CoG2: Resonance | Careful observation ensures that the bricolage process is deeply connected to stakeholder needs and contextual cues, enhancing resonance. |

| CoG3: Relevance | Listening to stakeholder feedback ensures that innovations are aligned with real-world needs, ensuring relevance. | ||

| Intimate Knowledge of Resources | Understanding and leveraging what is available. | CoG1: Reliability | Knowing what resources are available allows for consistent application in various contexts, supporting reliability. |

| CoG2: Resonance | Intimate resource knowledge ensures solutions resonate by using the most appropriate and contextually aligned resources. | ||

| CoG3: Relevance | Deep resource knowledge ensures that solutions are relevant by effectively matching resource application to needs. | ||

| Trusting One’s Own Ideas | Confidence in the innovative process. | CoG2: Resonance | Trust in one’s own innovative capacity fosters resonance by aligning solutions closely with personal and communal insights. |

| CoG3: Relevance | Self-trust ensures that solutions remain relevant by adhering to a vision that meets identified needs. | ||

| Self-Correcting Structures with Feedback | Adaptability and learning from implementation. | CoG1: Reliability | The ability to self-correct based on feedback enhances the reliability of bricolage by refining methods and outcomes. |

| CoG2: Resonance | Self-correcting mechanisms ensure resonance by continually adjusting solutions to better align with stakeholder feedback. | ||

| CoG3: Relevance | Feedback loops maintain relevance by ensuring that solutions evolve to meet changing needs effectively. |

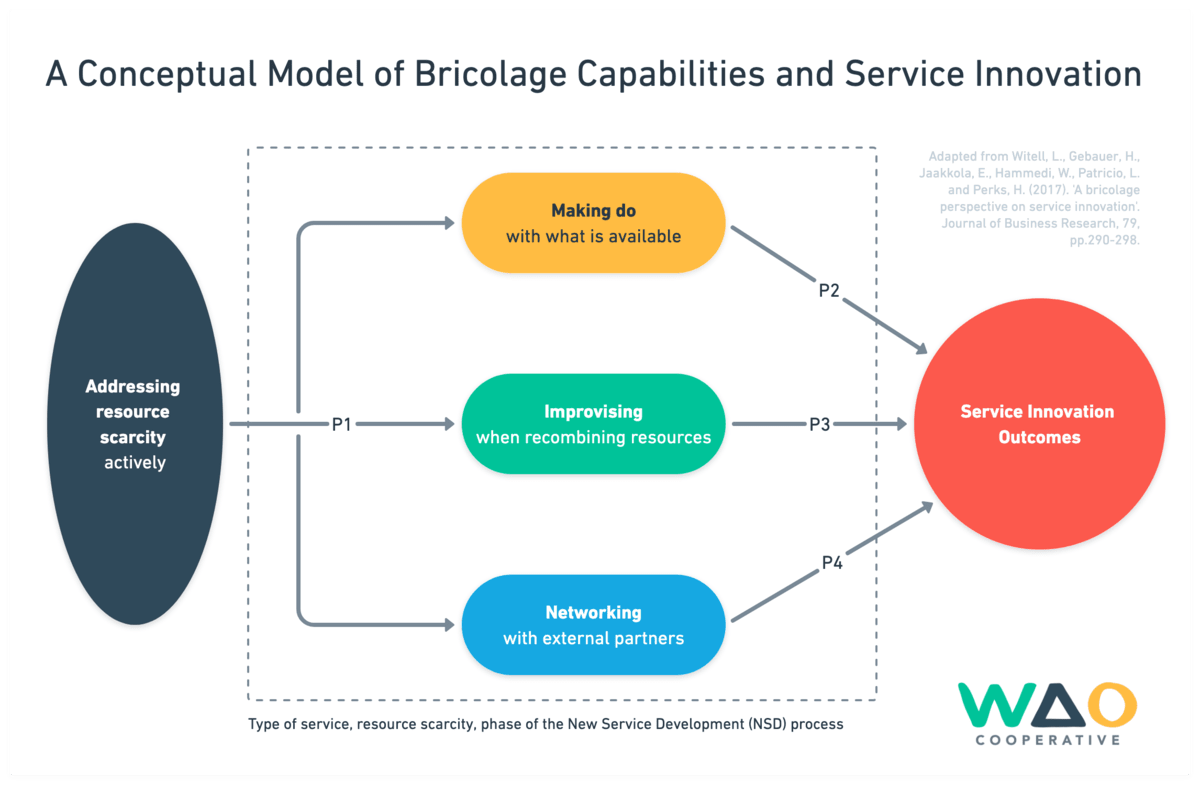

The bricolage paper contains four ‘propositions’ (Witell, et al., 2017, pp.295-296) some of which have an ‘a’ and ‘b part because they present competing hypotheses based on different theoretical perspectives or empirical observations.

Proposition 1

Addressing resource constraints actively is positively associated with strengthening bricolage capabilities of making do, improvising and networking.

This proposition suggests that when organisations or individuals actively confront and address their resource constraints, they enhance their ability to engage in bricolage effectively. This strengthens their capabilities to make do with what is available, to improvise solutions, and to network with others to acquire needed resources or knowledge.

So this highlights the importance of having a proactive stance towards resource limitations. By actively engaging with constraints, instead of bemoaning them, organisations can create a more innovative culture leading to resourceful approaches leveraging bricolage effectively.

Propositions 2a and 2b

Capabilities for making do with what organizations have at hand are positively associated with service innovation outcomes. (2a)

Capabilities for making do with what organizations have at hand are negatively associated with service innovation outcomes. (2b)

Propositions 2a and 2b are competing, or in tension, because they suggest different outcomes from the same bricolage capability. This reflects the ways that innovation can be complex and context-dependent

Proposition 2a suggests that the ability to use available resources effectively (making do) leads to positive service innovation outcomes. That is to say, ‘making do’ helps organisations innovate successfully because it encourages creativity and problem-solving within existing constraints.

In contrast, Proposition 2b suggests that relying solely on available resources (making do) can limit the scope of innovation and lead to less optimal innovation outcomes. This happens because ‘making do’ might prevent organisations from seeking out new resources or methods that could lead to more groundbreaking innovations.

So these competing views reflect the dual nature resource constraints in innovation. On one hand, constraints can spark creativity and lead to novel solutions (2a). On the other hand, too much reliance on limited resources can inhibit the development of more ambitious, potentially more impactful innovations (2b).

Proposition 3

Improvising capabilities are positively associated with service innovation outcomes.

This proposition states that the ability to improvise, that is “creatively recombine resources in novel ways under constraints,” is positively linked to successful service innovations. Improvisation is a core component of bricolage and is essential for adapting to and overcoming immediate challenges.

Proposition 3 supports the idea that flexibility and the ability to adapt quickly are crucial for innovation, especially in environments where conditions and resources can change rapidly.

Propositions 4a and 4b

Networking capabilities are positively associated with service innovation outcomes. (4a)

Networking capabilities are negatively associated with service innovation outcomes. (4b)

Like Propositions 2a and 2b, Propositions 4a and 4b are competing hypotheses regarding the impact of networking on innovation outcomes.

Proposition 4a suggests that the ability to network with external partners and collaborators contributes positively to innovation outcomes. Networking expands the resource pool and can bring in new ideas, both of which can enhance the innovation process.

Conversely, Proposition 4b suggests that networking might sometimes lead to negative innovation outcomes. This could be due to the complexity and coordination costs associated with managing multiple partnerships or because external inputs might dilute the organisation’s focus or lead to conflicts.

These propositions then lead to a diagram which I’ve recreated and adapted slightly. (I’ve used WAO colours and put the logo on because I can imagine us using this with clients!)

I found this activity, and especially the academic paper, really eye-opening. This is exactly the kind of work we do through the co-op, as opposed to, say, large consulting firms who encourage their clients to adopt templated approaches. It’s great to have another framework to apply to be able to show our clients an approach we can offer them.

References

- Belshaw, D. (2012) ‘What constitutes ‘rigour’ in our 21st-century educational systems?’. Connected Learning Alliance. Available at: https://clalliance.org/blog/what-constitutes-rigour-in-our-21st-century-educational-systems/ (Accessed: 18 May 2024).

- The Open University (2020) ‘1.4.1 Summarising use of systems and strategy’, TB872 Block 1 Systems and Strategy [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261477§ion=5.3 (Accessed 18 May 2024).

- Weick, K.E., Sutcliffe, K.M. and Obstfeld, D. (1997). Organizing for High Reliability: the mindful suppression of inertia’. University of Michigan, Business School, Research Support.

- Witell, L., Gebauer, H., Jaakkola, E., Hammedi, W., Patricio, L. and Perks, H. (2017). ‘A bricolage perspective on service innovation’. Journal of Business Research, 79, pp.290-298. Available at https://repositorio.inesctec.pt/server/api/core/bitstreams/7fa04ac8-d945-498f-aeb1-b6d61b1e6616/content. (Accessed 18 May 2024).

![What Constitutes ‘Rigour’ in Our 21st-Century Educational Systems? [DMLcentral]](https://dougbelshaw.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/dmlcentral-rigour-604x270.png)