TB871: 5 reasons why the unknown is not just a temporary or local state

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

The module materials (The Open University, 2020) outline five really useful reasons why the world is fundamentally unknowable:

- The overwhelming complexity of networks

- Processes that control stability and instability

- The unpredictability of developing patterns of relationships

- Social messes can be wicked

- Situations are not situations

Let’s consider at each in turn.

1. The overwhelming complexity of networks

Each person has a great number of different types of connections with humans. This exists within a vast network of close and distant relationships. So even with a relatively small number of people, number and nature of connections becomes highly complex. This increases exponentially when considering national or global populations, where a small number of individual connections contribute to an unfathomably large and intricate network. Counter-intuitively due to their size and complexity, large networks can often be resilient and maintain structural stability due to the sheer number of nodes.

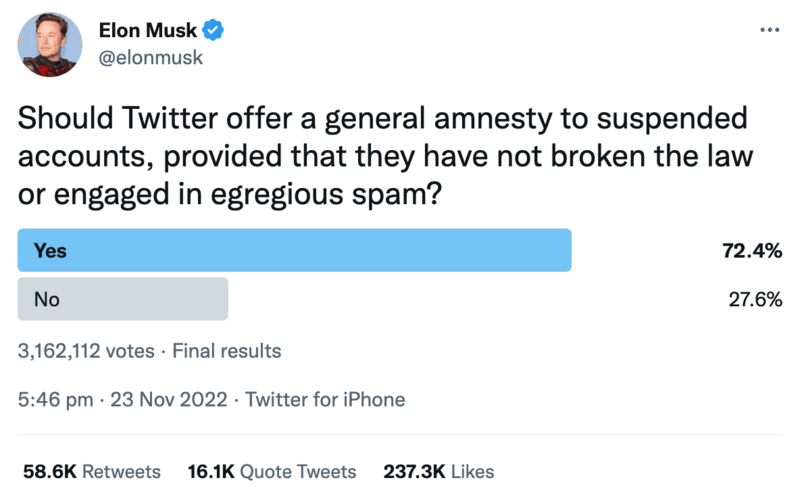

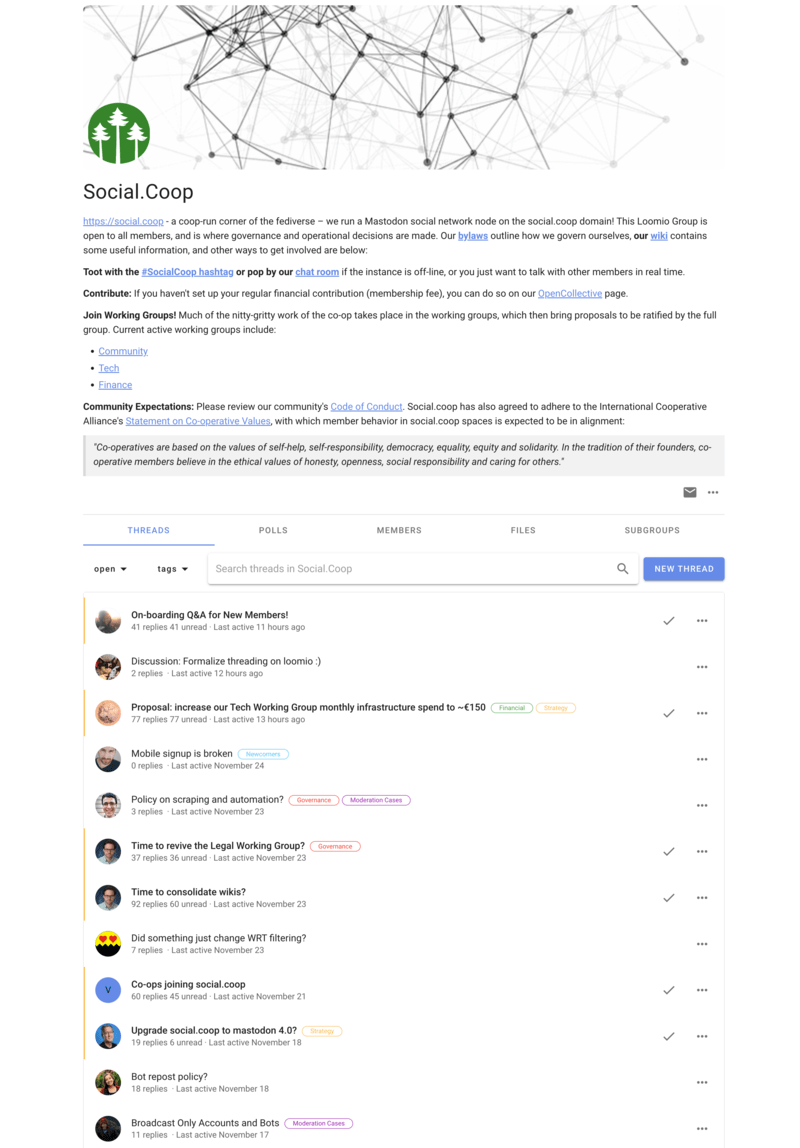

The inherent stability of these networks does not mean that individual outcomes cannot be unpredictable. Emergent outcomes and behaviours can be unknowable and unexpected, for example as we’ve seen with the assault upon online social networks through misinformation, hacking, and more. Rather than anticipating specific outcomes, we live in a world where we need to focus on preparedness and reconsider what ‘stability’ looks like. Historically, ecosystems and cultures have changed rapidly due to ‘tipping points’ that we’ll consider in the next section.

2. Processes that control stability and instability

There are two types of causal loops that are used primarily by systems thinkers: balancing loops and reinforcing loops. While balancing loops help maintain stability, reinforcing loops lead to growth or collapse. The idea of ‘tipping points’ is often used to identify how these loops form, although they can be triggered by tiny changes, which makes them difficult to predict.

Reinforcing loops explain why ‘first impressions’ are often seen as so important. For example, an initial positive or negative interaction can set of an chain reaction and compound and reinforce that first impression. Similarly, ‘trophic cascades’ in ecosystems shows how complex interactions can result due to the presence (or absence) or predators; multiple potential tipping points exist, so a single ‘tipping point event’ can trigger a cascade of others.

3. The unpredictability of developing patterns of relationships

There is something called Conway’s Game of Life which I don’t completely understand, but apparently is a mathematical simulation which uses simple rules to generate complex behaviours. I prefer the example of birds flying in formation, to be honest, but the point is the same: simple, rule-based systems can produce intricate, delicately-balanced outcomes that can be difficult to predict.

This obviously causes significant challenges around strategic planning. If we fit humans into stable patterns, then we can plan base on linear, predictable responses. If behaviours deviate, then planning becomes more complex. This, I suppose, is the difference between Homo economicus which is the rational view of humans presented by economic theory and, well, how humans actually act in the real world. As a result, strategic planning needs to recognise and address blind spots, stay flexible, and be aware how assumptions influence behaviours.

4. Social messes can be wicked

A ‘wicked problem’ is a form of unpredictable social mess that I’ve discussed before as part of this module, as well as in TB872. It’s “a complex, multifaceted problem with no clear solution, often characterized by interdependencies, changing requirements, and multiple stakeholders” to quote the latter post.

As I reflected on separately in a post about the croquet game in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, structured problem-solving is difficult because people don’t always ‘play the game’ or even understand the rules. Real life problems are somewhat unruly. They are often embedded deeply within complex networks of relationships, and can ‘cascade’ much like the trophic cascade within ecosystems mentioned above. There are conflicting perspectives, for example relating to the climate emergency, or rewilding, or almost anything you can think of. The only way to really deal with this complexity is to involve diverse stakeholders and be open to creating entirely new approaches.

5. Situations are not situations

Following on from ‘wicked problems’ the notion that ‘situations are not situations’ is a way of highlighting that our attempts to address or even contemplate a situation alters it in some way. It’s a bit like Schrödinger’s cat in that respect, because we’re never dealing with a fixed target, but rather a construct of language. Italian physicist Carlo Rovelli writes that, “a storm is not a thing, it’s a collection of occurrences” which starts to help us out of our linguistic trap of seeing stability where there is none.

Systems thinking therefore needs to embrace the fact that situations never stop changing. This means that tradition decision-making methods are likely to be ineffective, and even incremental change approaches might be limited in success because they assume static conditions rather than dynamic contexts. We must instead account for a fluid world in which we design or organise against a background of constant transformation.

References

- The Open University (2020) ‘P1.1.3 Unknowableness of the world’, TB871 Block 1 Systems and Strategy [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261478§ion=2.3.4 (Accessed 22 May 2024).

Image: Dim Hou