Solving for complexity

If there’s one thing I’m called upon to do time and again in my work, it’s to untangle complexity. The result of this is not simple but instead a distillation that nevertheless includes simplification and prioritisation of complex issues.

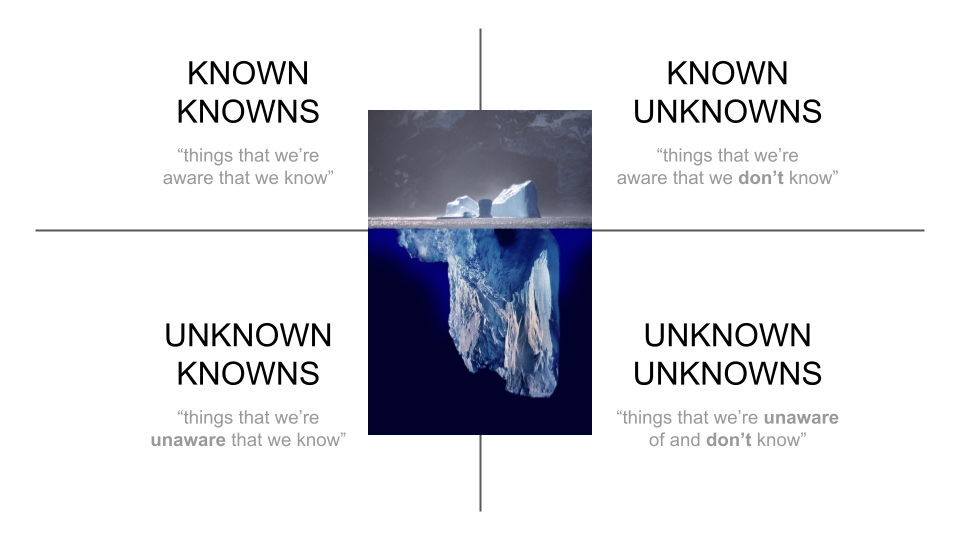

One way of doing this is to use a framing popularised by Donald Rumsfeld in a press briefing back in 2002:

There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

Donald Rumsfeld

As the philosopher Slavoj Žižek pointed out a couple of years later, there are also ‘unknown knowns’, the things we’re unaware that we (or our community/organisation) know.

Let’s use the example of software vulnerabilities. There are those that your team knows about and needs to fix. These are your known knowns. In addition, there are vulnerabilities that you are aware must exist (it’s software!) but you don’t known about them yet. These are your known unknowns.

Both known knowns and known unknowns can be thought of as being the ‘tip of the iceberg’, the bit that you can see and understand. Beneath the surface, however, lurk things of which you’re unaware. These take concerted effort to get to.

Continuing the software analogy, there are attack vectors that are known within the communities and networks of which your team and organisation are part. There is a latent knowledge, some unknown knowns that need surfacing in order to become known knowns.

Beyond that, looking at the bottom-right of the grid, there are unknown unknowns, perhaps new (or rediscovered) techniques which could be used, but need much research and synthesis to discover.

Most organisations I work with are aware of the top of the iceberg. They know what they know, and they are aware of the things that perhaps they don’t know. What they need help with are the things that are beyond that.

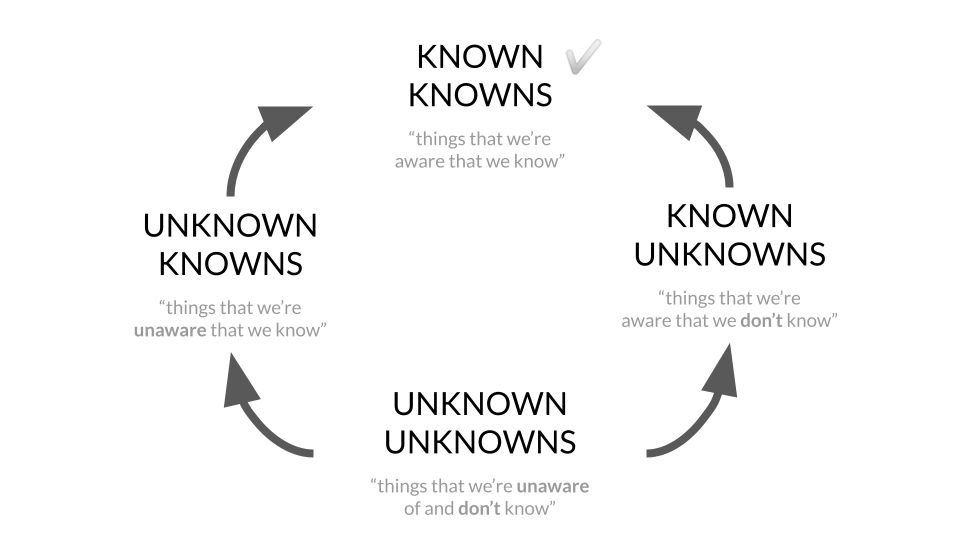

So how do we prioritise this work around the unknown when everyone’s busy with their day job? The answer is to include all of it in strategic planning, to explicitly move from unknown unknowns through to known knowns in a systematic way.

This can sound quite abstract so let’s once again use a more tangible example. Let’s say that you’re an NGO and trying to make a difference in the area of climate change.

👍 Known knowns — these are things that the NGO knows make a difference either in terms of accelerating or slowing down the rate of climate change. This is the core of their activism and campaigning.

🤔 Known unknowns — these are the areas that the NGO is unsure about and perhaps needs to do some more research. They know how to do this, and so just need to raise money to do the research and move this towards being a known known.

🕸️ Unknown knowns — these are the things that are known by the NGO as a whole, or by the network or community around it. New staff members might not be aware of this latent knowledge, so the best thing an organisation can do to surface these is documentation. Wikis are particularly useful in this regard.

🕵️ Unknown unknowns — these are things outside of the knowledge, experience, and understanding of the NGO and the network and community around it. Historically, these have often been technological, so for example solutions to problems, or new problems that may be caused by inventions/developments.

This last area, unknown unknowns is the reason that organisations need to employ generalists as well as specialists: people who are interested in lots of things as well as people who spend their time on just one thing.

Isaiah Berlin’s essay The Fox and the Hedgehog is a useful way of unpicking the difference between the two. In a nutshell, hedgehogs are those who try and fit everything into one unifying view of the world, whereas foxes are happy to know many different kinds of things in many different ways. Every organisation needs ‘foxes’ that are aligned with the mission, giving them time to explore and discover things from unusual places that might be beneficial in surfacing unknown unknowns.

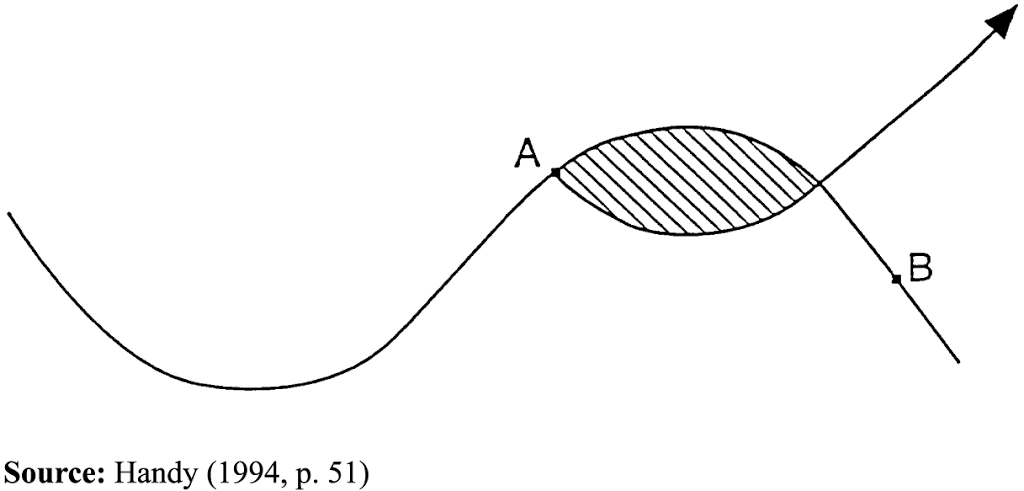

None of the above is easy, and it can feel like it’s outside of the scope of the everyday running of an organisation. At this point in the conversation with clients, friends, and anyone who will listen, I refer to Charles Hand’s sigmoid curve, which is shown below.

Without effective horizon-scanning for both unknown knowns and unknown unknowns, organisations wait until it’s too late (point B) to make changes which will put them back on the path of growth.

As shown by the diagram, it is at point A, during a period of growth, that new knowledge, experience, and understanding should be added to the mix. This allows for the next cycle of growth to happen, but also means a period of time where there is uncertainty and doubt. This is indicated by the shaded area.

To conclude, this kind of work can seem quite disconnected from the core business of organisations. When we’re busy trying to make better widgets, solve world hunger, or sell more stuff, this kind of work feels like a ‘nice to have’ rather than core to organisational success.

However, I would say that the opposite is true: anyone can create an organisation that can secure some funding and last a few years. The history of both Silicon Valley and your local high street is testament to that. What organisations that have been around a while know, however, is that it’s precisely this kind of work that leads to long-term growth and sustainbility.

Need some of this? You can hire me! Get in touch

This post is Day 85 of my #100DaysToOffload challenge. Want to get involved? Find out more at 100daystooffload.com.