TB872: Core reading for my EMA

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

I’ve spent the last few sessions for my MSc in reading and making notes for my End of Module Assessment (EMA). I’m sharing quotations from following ‘core‘ reading (see previous post) on the understanding that I may or may not get to the ‘extra‘ reading that I’ve set myself. I’ll also add an ‘additional references’ section to the bottom of this post with ‘potentially-relevant further reading’ (a.k.a. ‘extra extra’ reading) 😅

Given that I do have a tendency to over-think things, and I’m moving house before my EMA is due, in this case perfect is very much going to be the enemy of done. What follows are relevant quotes I’ve pulled from my ‘core’ reading.

Note in passing: I’m not entirely sure why I’m not using a wiki for this. For my initial Ed.D. I used TiddlyWiki which is still around (although the images are b0rked). These days I’m tempted to use Obsidian, especially given the existence of Obsidian Publish. Maybe for my next module?

Relevant quotations from core reading

Bawden, R. (2004)

Bawden, R. (2004) ‘Angst, agoras, and academe – reflections on an experience in conscious evolution’, World Futures, 60(1), pp. 53–66

- Discourse is a process of collective learning focused on consensual action: “In essence, discourse is a process of collective learning that has as its purpose, consensual action, and as learning is the business essentially of academe, then it might then be expected that the academy would be at the forefront of change; a major contributor to the construction of agoras and a key facilitator of a ‘critical discourse for systemic change’. This represents a very significant issue, for “…..few institutions are devoted to helping the public to form considered judgments, and the public is discouraged from doing the necessary hard work because there is little incentive to do so” (Yankelovich, 1991).” (p.55)

- 5 frameworks of ideas key to CSLS: “[A] number of particular conceptual models and ‘frameworks of ideas’, did assume foundational characteristics. These included key ideas, theories or/and practices concerned with (a) experiential learning as presented initially by Kolb (1984), (b) of the soft systems methodology as a learning process as proposed by Checkland (1981) (c) of levels of learning as posited by Bateson (1972), (d) of levels of cognitive processing as developed by Kitchener (1983), and (e) of epistemic/systemic connections as developed by Salner (1986). While theories, philosophies and practices from a great many other scholars have informed subsequent developments, these five models have proved foundational to the direction of endeavours. In essence they have together provided a framework for what might be referred to as ‘guided systemic discourse’, where the intention is to facilitate systemic understanding by people who might not normally take such a position, or even be aware of its nature and potential advantages.” (p.60)

- Self-organising critical learning system based on 3 levels of learning: “The work of Bateson (1972), Kitchener (1983), and Salner (1986) provided the basic logic for understanding how ‘learning systems’ could be both self-reflective and transformative. ‘Critical learning systems’ could be designed such that would concern themselves concurrently with (a) learning about ‘matters to hand’ (level one), (b) learning about how that learning occurred (as level two or meta learning) and, (c) learning about the nature of knowledge and the significance of paradigmatic assumptions that frame the way learning is conducted and knowledge is created (as level three or epistemic learning). Learning could thus itself be construed as a nested hierarchy/holoarchy of self-monitoring and self-organizing systems, where each level of system has the capacity to influence and be influenced by the others in which it is embedded. Each ‘level’ therefore also provides a context for the operations of the others, as well as mechanisms for the monitoring, interrogation and evaluation of them. Learning systems are thus inherently critical, and indeed developmental, for critique can serve as a trigger for change and development where and when the need is indicated.” ( p.61)

- CSLS uses a range of worldviews to inform each other and fuel emergence: “Critical learning systems are able to not only embrace different ways of knowing and different worldviews and perspectives associated with different paradigmatic assumptions but to use such differences ‘to inform each other’. In this manner, normative and empirical forms of inquiry for instance, can be incorporated into an integrated systemic inquiry where the ethical and the instrumental can inform each other. The same idea of integration can be envisaged for experiential, inspirational, propositional, and practical learning modes. And so on: Where difference exists, it can be used to fuel emergence!” (p.62)

Bawden, R. (2005a)

Bawden, R. (2005a) ‘A commentary on three papers.’ Agriculture and Human Values, 22, pp. 169-176.

- Shift in systemicity (intellectual and moral development of actors): “In essence, they each reflect what Checkland and Holwell (1998) refer to as ‘‘a shift in systemicity,’’ ‘‘from assuming that the world contains systems, to assuming that the process of inquiry into the world can, with care, be organized as a learning system.’’ And I want to reinforce the importance of this shift by introducing the argument that responsible acts of development of the material world of ‘‘people and things’’ demand the intellectual and moral development of the actors involved. Bringing these two ideas together, I will argue that the systemic development of complex, purposefully-managed, natural resource systems is essentially a function of the development of the consciously reflexive and critical learning systems embedded within them.” (p.169)

- Four themes in CSLS: I can now segue into the meta-theme of critical learning systems that I mentioned at the start and which finds particular relevance in a number of sets of overlapping themes of the three papers: (1) multi-stakeholder groups and the significance of trust and rapport to effective participation; (2) holistic complexity, conflict, and the significance of learning and learning about learning; (3) learning about learning, and the nature and significance of different ‘‘learning loops’’ and ‘‘levels of critical reflection’’; and (4) criticality and modes of ‘‘systems thinking.’’ (p.171)

- Contextual relativism: “The epistemic structures and processes through which people make sense of, and make judgments about, their world, can ‘‘progress’’ from a state of ‘‘dualism’’ and straightforward choice born of certainty, to much more complex evaluative position of ‘‘contextual relativism’’ which demands recurrent commitment to the search for improved understanding and judgment (Perry, 1970).” (p.172)

- Collective work on experiential challenges facilitates epistemic development: “Collective work on tasks that involve experiential challenges, can greatly facilitate epistemic development, which can be seen to represent the third of a three-level process of cognitive processing (Kitchener, 1983) and of learning: We can learn about the matter to hand (cognition); we can learn about how we come to learn about the matter to hand (meta-cognition); and we can learn about the nature and limits to knowing that frames the other two levels (epistemic-cognition).” (p.172)

- Definition of a system: “Systems are coherently whole entities that are both composed of interacting components and defined by their nature and by the nature of the relationships between them that are cybernetically regulated. A system has a boundary that contains the component sub-systems that are embedded within it, while separating it from the environmental supra-system in which it itself is embedded and to the cybernetic influence of which it may be ‘‘open’’ or ‘‘closed.’’ A key feature of this sub-system–system–supra-system hierarchy is that each ‘‘level’’ has characteristics that are unique to it and that cannot be predicted from studies at other levels. These emergent properties are born of the ‘‘tensions of difference’’ that exist both among the sub-systems and between the system and its supra-system.” (p.172)

- CSLS as ‘third wave’ systems thinking: “As Midgley (2000) sees it, this third wave was built upon three essential sources of criticism of the second wave: (1) concern for power relationships within systemic interventions (Jackson, 1982); (2) concern for conflicts built into the structure of society (Mingers, 1980); and (3) concern for the cultivation of emancipatory interests in the development process (Ulrich, 1983).” (p.174)

- Boundary critique central to ‘third wave’ systems thinking: “The idea of ‘‘boundary critique’’ or critical boundary judgment is a central feature for ‘‘third wave’’ systems thinkers. As exemplified by the work of Ulrich ‘‘the boundaries, structures, and goal states of social systems are not defined physically, as in the case of organisms (including humans as ‘‘living beings’’) but rather by contexts of meaning’’ (Ulrich, 1983; emphasis in original). Stakeholders are involved not just in the exploration of particular situations but in decisions about which situations merit critical attention in the first place.” (p.174)

- Coercion/emancipation vs self-reflexivity: “Critical systems thinkers place matters of coercion and emancipation from restrictive power relations at the very center of their activities – and that includes their own activities of intervention. Typically, however, this self-reflexivity does not also explicitly include the idea of self-development of their capacities to be self-reflexive. Indeed, while the claim is made that through participating in any systems methodology, stakeholders often gain a much greater appreciation of complex situations than they previously enjoyed, there is little attempt in any of the approaches to deliberately nurture the development of what might be termed the epistemic status of stakeholders. It is all very well to discover that one has a worldview, and that one can even adjust it to accommodate the worldviews of others and even to deal with coercion. It is quite another thing, however, to appreciate the complexity of the elements that provide the epistemological, ontological, and axiological foundations of worldviews, and to learn how to develop these to more mature epistemic positions.” (p.174)

- CSLS need to reach a level of epistemic development before they can comprehend their own systemicity: “Critical learning systems need to reach a level of epistemic development before they can comprehend their own systemicity. This eventually expresses itself, however, in terms of the comprehensive appreciation of: (1) their internal systemic relationships (e.g., as a coherent group of stakeholders); (2) the systemic relationships that they have with ‘‘higher order systems’’ in which they are embedded (e.g., ‘‘agri-ecosystems,’’ ‘‘agric-food systems’’ etc.); and (3) the systemic relationships that they have with the even higher environmental supra-systems in which those systems are embedded (e.g., ‘‘natural’’ and ‘‘cultural’’ systems).” (p.175)

Bawden, R. (2005b)

Bawden, R. (2005b) ‘Systemic Development at Hawkesbury- Some Personal Lessons from Experience.’ Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 22, pp. 151-164.

- Most important lesson from Hawkesbury: “Cutting to the quick with my answer to my questioner: the most important lesson that I learned from my Hawkesbury days is that inclusive development of well-being within any complex and messy context (such as agriculture within its natural and cultural environments) is a critical function of the intellectual and moral development of all of those who are directly involved in, and or affected by, such development endeavors.” (p.4)

- Experience goes beyond the senses: “[E]xperience has a much more systemic connotation than merely the use of the senses to detect changing physical surroundings or to empirically recognize simple problems: Experience “recognizes in its primary integrity no division between act and material, subject and object, but contains both in an unanalyzed totality” (Dewey, 1910)” (p.5)

- Neoliberalism as social and moral philosophy: “Neo-liberaleconomics, on the other hand, has taken the opposite stance, by itself becoming “a social and moral philosophy” in which “the existence and operation of a market are valued in themselves” and “where the operation of a market or market-like structure is seen as an ethic in itself, capable of acting as a guide for all human action, and substituting for all previously existing ethical beliefs” (Treanor, 2004). Yet, as Sen (1988) argues, there is little evidence for the claim that the maximization of self-interest provides the best approximation of human behaviour or that it leads necessarily to optimum economic conditions.” (p.12)

- What and how we learn depends on prior experience: “There is ample research evidence for instance, to support the thesis that prior knowledge, beliefs, skills and experiences have a major influence both on what is learned from subsequent experiences and how it is both learned and contextualized (Piaget, 1972), (Vygotsky, 1978). In this manner we not only come to know ‘more’ about the nature of the world about us, but also to develop different ways of knowing and different assumptions about the very nature of knowledge itself. In essence, our experiences in life promote a sequence of intellectual and moral development in each of us, that in essence strongly suggests that “knowledge structures and the process through which information is organized and made usable, can progress from a state of simple absolute certainty into a complex, evaluative system” (West, 2004).” (pp.16-17)

- Lack of a coherent epistemology: “We can know and we can come to know how we know. We can also come to know about knowledge itself and about the limits to knowing, as suggested by Bateson (1972), in his explication of different ‘levels of learning’, by Mezirow (1991) with his work on transformative adult learning, and by Kitchener (1983) with her tri-level model of cognitive processing… We are characteristically non-reflexive either as individuals or as institutional collectives – as the old adage has it with its clever use of words, we do not even know that we have an epistemology, let alone what it is!” (pp.17-18)

- Epistemic development contains epistemological, ontological, and axiological assumptions: “Given the close connection that these scholars have identified between epistemological, ontological, and axiological assumptions, it is useful to extend the use of the phrase epistemic development to embrace development with respect to all three.” (p.19)

- Definition of a critical learning system: “A critical learning system is a construct of a group of people who consciously organize themselves self-consciously if they were coherent and whole ‘system’ of interconnected ‘learning sub-systems’ that are collectively self-reflexive while together operating in environments with which they are structurally coupled and with which they are attempting to co-develop through learning processes (Bawden, 1994).” (p.21)

- CSLS as a ‘fourth’ school or wave of systems thinking: “Ideas, principles, theories, philosophies and methodologies for the organization, structure and activities of critical learning systems are drawn from all three ‘schools of systemics’ of ‘hard’, ‘soft’ and ‘critical’ (Jackson, 2000). Furthermore, experience with its use as an heuristic in a wide diversity of circumstances indicates the nature of a fourth school – or, adopting Midgley’s (2000) interpretation of the schools as ‘waves of systems thinking’, a fourth wave of systemics.” (p.21)

- From the first or ‘hard’ school/wave: “the idea that a group of people can be construed as a ‘social system’ of subjctive and objective elements, which deliberately and consciously develops a sense of its own wholeness and the inter-connectedness of its own parts.” (p.21)

- From the second or ‘soft’ school/wave: “comes the shift in systemicity from the world to ways of inquiring into the world (Checkland, 1981). Rather than an emphasis solely on soft systems methodology which is seen to yield learning about the various elements of ideas framework, methodology, and area of concern (Checkland, 1985), it is the process of critically reflexive learning itself that is privileged.” (p.22)

- From the third or ‘critical’ school/wave: “comes a further shift in emphasis that reflects a number of different aspects of criticality. Drawing on Midgley (2000) the ‘critical turn’ in systems thinking calls attention to three foci that include (a) concern for power relationships within systemic interventions (cf Jackson, 1982), (Jackson,1991), (b) concern for conflicts built into the structure of society (cf Mingers, 1980), and (c) concern for the cultivation of emancipatory interests in the development process (cf Ulrich, 1983). Within the CLS construct, these are added to the concern for the epistemic and meta-cognitive implications for knowing and learning and for public judgment. Added also, is concern for the potential consequences of development interventions on both cultures and nature alike. Reflexivity thus now becomes multi-dimensionally critical.” (p.23)

- Also: “This third dimension of criticality places a greatly increased emphasis in critical learning systems on axiological aspects of development of both the learning sub-systems themselves and of the ‘world’ in which they are attempting to systemically intervene. The emancipatory interest of Habermas (1984) is now privileged, and a critical pedagogy is indicated through which “the oppressed come to perceive the reality of oppression, not as a closed world from which there is no exit, but as a limiting situation which they can transform” (Freire, 2003).” (p.24)

- Inspirational learning vs experiential learning: “Inspirational learning, in contrast to experiential learning, asks us not to immerse ourselves in the ‘real external world of the concrete’ (the sensual) nor to conceptualize the abstract’ (the conceptual), but to ‘disengage’ from ‘reality’ and seek ‘internal insight’ through some form of meditation or contemplation (Bawden, 2000). This process will often encompass a spirituality that transcends the nihilistic tendencies of the existential that Kohlberg and Ryncarz (1990) argue “relies in part upon the self’s particular and somewhat unique life experience”. And this emphasis again on experience, in the richest sense of that word, evokes the work of Goethe with a ‘science of conscious participation in nature’ through which he came to see the “wholeness of the phenomenon by consciously experiencing it” in a manner where “this experience cannot be reduced to an intellectual construction in terms of which the phenomenon is organized” (Bortoft, 1996). As Bortoft argues, Goethe was concerned with the transformation of consciousness itself from “a piecemeal way of thought to a simultaneous perception of the whole” (Bortoft, 1996) leading to a state in which a relationship could be “experienced as something real in itself” within an ‘holistic’ context.” (pp.26-27)

Boxelaar, L., Paine, M. and Beilin, R. (2006)

Boxelaar, L., Paine, M. and Beilin, R. (2006) ‘Community engagement and public administration – of silos, overlays and technologies of government.’ Australian Journal of Public Administration, 65(1), pp. 113-126.

- Legitimate knowledge is contested: “However, with many contemporary societal issues we are faced with a situation where what is considered legitimate knowledge differs from one situation and group of people to the next. There is often no single and comprehensively accepted body of knowledge that can be referred to in order to settle debates, and consequently uncertainty prevails. Moreover, many issues are so complex that they are beyond the capacity of one single agent to grasp and control. As Alford argues, ‘the knowledge and capacity to generate insights into these problems is distributed across those who have some stake in it’ (Alford 2001:12).” ” (p.113)

- Problems around using a positivist evaluation process for a constructivist project: “NRE/DPI’s evaluation support team advocated the use of Bennett’s hierarchy (Bennett 1976) for project development and evaluation. Bennett’s hierarchy refers to a hierarchy of steps in a program or project and provides a program logic that can be used for both project development and evaluation. This framework was developed through an analysis of the chain of events within agricultural extension programs (Department of Natural Resources and Environment. Evaluation Support Team, 2002). Programs and projects within NRE and DPI were encouraged to produce a report, or ‘performance story’, in terms of the steps in Bennett’s hierarchy… Some team members expressed concern about the contradictions between the project’s constructivist soft systems orientation that emphasized the emergent nature of change, and this approach to evaluation that conceptualized change as linear. However, the use of Bennett’s hierarchy was justified as it was considered useful in communicating what the project was about in terms that others within the organization would understand. It was argued by evaluation support staff that projects within the organization could ‘talk to each other’ and be compared through the use of Bennett’s hierarchy. The use of Bennett’s hierarchy facilitated accountability, legitimacy and credibility of the project within the organization.” (pp.119-120)

- Government regimes of practice vs constructivist discourse: “What emerges from this analysis is that project narratives were constructed in both positivist as well as constructivist discourse. According to the former, participation by stakeholders occurs within parameters set by government, as the linear approach it entails ensures that government remains the owner and driver of the development process. This is likely to lead to the kind of community engagement that assimilates community and other stakeholders into government regimes of practice (cf. Dean 1996), or government through community (Rose 1996:332-336). Constructivist discourse about the project, on the other hand, reflects the emergent nature of change and the contextual embeddedness of all participants in the project. This translates into a change program that deconstructs the dichotomy between government and other stakeholders and creates a space for genuine collaboration, where other stakeholders can perform their identities in a way that does not assimilate them intoor marginalize them from government practices and priorities. In the DSC project the positivist narrative prevailed and this impeded the effectiveness of the project to create a space for genuine participation of diverse stakeholders in natural resource management.” (p.121)

Ison, R. and Russell, D. (2000)

Ison, R. and Russell, D. (2000) ‘Exploring some distinctions for the design of learning systems.’ Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 7(4), pp. 43-56.

- Learning systems as models: “What do we mean by a ‘learning system’? From our perspective it is possible to speak about, and act purposefully to design or model a ‘learning system’. However, it is only possible for a claim to be made that a ‘learning system’ has been experienced through participation in the cycle of activities in which the thinking and techniques of the design or model are enacted and embodied. An implication of this logic is that a ‘learning system’ can only ever be said to exist after its enactment – that is on reflection. It is important to remember that a model of a ‘learning system’ is just that – a model.” (p.2)

- Dualism vs duality: “Two concepts form a dualism when they belong to the same logical level and are viewed as opposites. The logic behind this dialectic is negation. Two concepts form a duality when they belong to two different logical levels and one emerges from the other.” (p.3)

- Enthusiasm as a higher order concept: “Initially we saw enthusiasm as a higher order concept in which those who were “enthusiastic” appeared more able to manage their own realities and to accommodate change. Our experience with the limitations of “information rich and poor” and our conscious introduction of the alternative metaphor “enthusiasm” can be seen as a critical incident. A critical incident for us was where an existing organising metaphor was unable to coherently organise or synthesise our experience. We thus consciously introduced one that we felt did the job better. From this experience it was proposed that it might be possible to generate or trigger enthusiasm in people by valuing and appreciating them for who they were and for what they were doing, not unlike we had been doing in our very open-ended interviews with farmers. Our proposition assumed that all people were information rich and thus capable of making the best sense of their realities.” (pp.13-14)

- Enthusiasm as a methodology: “Enthusiasm as a methodology was built on the use of narrative. The methodology was underpinned by the biological understanding of the drive itself as well as the theoretical principles. Our desire was to shape our engagements in a way that did not re-direct a person’s energy – the role of theresearcher/facilitator was to find out where a person’s energy was. This is the initial task in the methodology. But to do this the right sort of questions are needed: what do you want to do, why are you what you are, what is it you get out of this sort of work that is satisfying? To get to the point of having that sort of conversation requires a respect for the individuality of the other and acceptance that whatever they are going to say is valid – based on the notion that it is the ‘god’ within that person which has to be respected. The aim was for participants to be able to tell their story about where their energy comes from and how they see it expressing itself and what they see as obstacles to it’s manifestation.” (p15)

- Enthusiasm and narrative are related concepts: “Our conclusion was that narrative and enthusiasm are recursively related concepts. Narrative allows development of a methodology for the expression of enthusiasm so that researchers, managers etc., can actually go out and talk to people about their enthusiasm by asking them to tell stories about their lives. Narrative, the telling of stories, also puts the story teller in touch with their own enthusiasms, and in the telling can trigger similar enthusiasms in others.” (p.16)

- Four stage process for triggering enthusiasm (pp.16-17):

- Active listening

- Invitation to a space for options (conscious/unconscious)

- Actions taken to maintain conversation

- External resources (e.g. money, tech) as amplifiers or suppressors of enthusiasm

- Additional two stages for development of enthusiasm as a R&D methodology (pp.17-18)

- Design of processes to bring people together who share common ‘enthusiasms for action’

- Critical reflection should be an essential part of the use of enthusiasm as a methodology

- Four stage process for triggering enthusiasm (pp.16-17):

- Shortcoming in Kolb’s theory: “Luckett and Luckett (1999) identify four shortcomings in Kolb’s theory from a situated learning perspective: (i) learning is a social rather than an individual activity and is best carried out collectively in a community of practice; (ii) the structure of cognition does not reside in the individual mind but is rather widely distributed throughout the social and physical environment; (iii) the individual does not internalise experience, but this usually remains tacit (i.e. Kolb’s abstract conceptualisation would not be seen as a necessary part of the process of learning because it need not be explicit and declarative) and (iv) it is the authenticity of the activity that is paramount for learning – engagement in a human activity is already learning, it is not necessary to transform this experience into ‘knowledge’ for it to be recognised as learning.” (p.20)

Ison, R. and Straw, E. (2020)

Ison, R. and Straw, E. (2020). The hidden power of systems thinking – governance in a climate emergency. Abingdon. Routledge.

- Definition of ‘system’: “The word ‘system’ comes from the Greek verb synhistanai, meaning ‘to stand together’.A system is a perceived whole whose elements are ‘interconnected’. Someone who pays particular attention to interconnections is said to be systemic. The whole may be made up of institutions, government bodies, ministers, staff, and assets, all in a complex network of relationships functioning to varying effect. Out of the end of all this, someone actually does something for or to someone. Systemic thinking and practice are about understanding what this whole is there for, how it works and embarking on its reform. This understanding has been developed into a set of concepts that are applied and adjusted or changed whilst being used to improve a situation. The technical terms draw on circular, recursive, multi-relational understandings and actions.” (p.14)

- Systematic as solid, systemic as liquid: “To appreciate the difference, look upon systematic as applicable to solids and systemic to fluids. When governments try to ‘pick up’ a fluid as if it were a solid, it slips through their fingers. As in chemistry, much of what is happening inside the fluid is unseen.” (p.14)

Ison, R.L. (2023)

Ison, R.L. (2023). ‘Beyond covid – reframing the global problematique with stip (Systems thinking in practice)’, Journal of Systems Science and Systems Engineering, 32(1), pp. 1–15.

- Origin of term ‘problematique’: “Turkish-American cybernetician, Hasan Özbekhan (1970), introduced the ’global problematique’ in a report to the Club of Rome, ’The Predicament of Mankind,’ to refer to the ’bundle of problems’ confronting humanity at that time… Importantly…, as outlined by Khayame, Collins and Ison (2021) ’when he uses the French term “problématique” for the first time in the history of Anglo-Saxon traditions of cybernetics and systems’ his use of ’problématique’ does not only mean seeing a wicked problem, it also entails experiencing an emotion of engaging in an inquiry that can embrace complexity. In other words, the idea of problématique frames thinking in terms of improving a complex situation (rather than solving a simple problem), and triggers an intention to learn about how to improve it. Özbekhan proposed the problëmatique as an antidote to ’…the all-pervasive analytic or positivistic methodologies which, by shaping our minds as well as our sensibilities, have enabled us to do what we have done’. (p.2)

- Social world we inhabit constrained by four things: “The social world we inhabit is severely constrained by:

- explanations we accept that are no longer relevant to our circumstances;

- outdated historical institutions (in the institutional economics sense) that contribute as social technologies to a broader human created and ungoverned technosphere;

- inadequate theory-informed practices, or praxis, and

- governance systems no longer adequate for purpose. (p.2)

- Problem of reifying terms: “Terms like ’problematique’, wicked and tame problems, complex adaptive systems, social-

- ecological systems and the like, are all neologisms invented to facilitate our conceiving of particular phenomena in the world. In other words, they are human inventions as is the term ’ecosystem’ (Tansley 1935), formulated to aid human ways of knowing about the world. Unfortunately, as Ison, Collins and Wallis (2014) explore, the practical implications of what we humans do when we invent and use terms such as these is that they become reified as ’things in the world’ rather than conceptual devices with the possibility to both reveal and conceal (McClintock, Ison and Armson 2004) i.e. to aid knowing as well as not-knowing. Theses neologisms through their reification and use by practitioners frame the ways in which we engage with the world because language operates like a mediating social-technology (Ison 2017b). Hence, as Lakoff (2010) notes: “all thinking and talking involves ’framing’. And since frames come in systems, a single word typically activates not only its defining frame, but also much of the system its defining frame is in.” In attempting to innovate, to change our relationships within, and to, the world we have to take responsibility for our framing choices. (pp.2-3)

- Problem of university structure: “It can be argued that the current organization called the ’university’ with its constituent institutions (e.g. disciplines; projects; research rankings etc) is poorly equipped to foster the ways of thinking and acting needed for responding to the global problematique. Some of the systemic failings include: perpetuation of disciplinary silos; inadequate institutions to foster inter- and trans-disciplinarity (Ison 2017a); inadequate problem/opportunity framing; unacknowledged epistemological tyranny – a form of epistemological injustice (Fricker 2007) played out in paper refereeing, project reviews and evaluations and promotion practices and over adherence to the linear, first-order, tradition of knowledge production and transfer which infects teaching and research (Ison and Russell 2000, Ison et al 1996).” (p.4)

- Potential solution to university structure: “Wolff (2018) offers a critique of academic practice, implying that more than institutional innovation is needed. In critiques of this type it would be good to see a refocus on praxis, a shift from the abstract and disembodied to embodied, situated and context-sensitive praxis which is realized through self-organization, co-design and deliberative processes building on much deeper understandings of past R&D success,

- failures and systemic affordances (Ison and Straw 2020).” (p.4)

- Trap of ‘knowledge transfer’ and ‘roll-out’: “Universities, and practitioners in many academic fields, have become trapped in the limitations of the linear model of innovation which can be expressed in several forms: knowledge or technology transfer; knowledge extension and/or adoption; knowledge uptake etc. (See Ison and Russell 2000, Ison and Russel 2011). As outlined by Ison, Röling and Watson (2007) much policy development is also trapped by the limitations of the linear, hierarchical model i.e., name problem, apply fixed forms of knowledge to the problem, devise and ’roll-out’ policy for adoption or implementation. Policies are often in the form of regulations, education or fiscal/market mechanisms. Rarely are monitoring and evaluation of the policy effectiveness undertaken i.e., there is often no inbuilt feedback, or if there is, the feedback is so attenuated as to apply to a situation (or problem framing) that no longer exists.” (p.8)

- ‘Systemic dance’ and hammer metaphor: “There is also a limited understanding, which can be drawn from sociology and philosophy of technology studies, of the ’systemic dance’ between humans and technology. To focus only on the hammer (a tool or technology) and not the hammerer, hammered, hammering relationship as part of a situated practice exemplifies systemic failure on the part of scholars, innovators and regulators.” (p.8)

- Uses of technology: “A key question becomes will technology serve creative coevolution through systemic governance or be used for social control / manipulation?” (p.9)

- Ison on CSLS: “Following Bawden (2010), this opportunity can be understood as a collection of organisations (with ’members’) who agree to act together as a coherent group of people who are prepared to ’collectively learn their way through’ an issue that they all agree is problematic in some way or another to them all. There is no recipe for the way ahead – hence it is useful to:

- frame any purposeful endeavour as a systemic co-inquiry

- invest in situation framing and deframing methods and cybersystems methodologies – use these to deframe and re-frame key concepts and understandings…

- collectively build a praxis for engaging in (managing and governing) situations usefully framed as wicked

- know and articulate your theory of change – ask: is yours ethically defensible?

- take responsibility for your own practice in cybersystemic terms (pp.10-11)

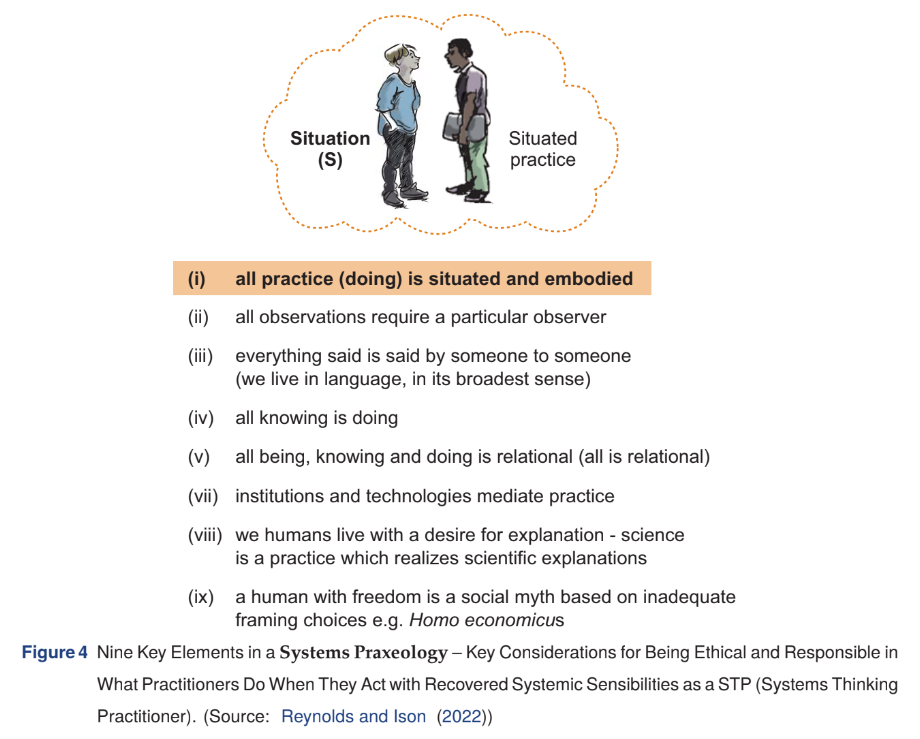

- Systems Praxeology: (p.12)

Jackson, M.C. (2006)

Jackson, M.C. (2006). `Creative holism – a critical systems approach to complex problem situations’, Systems research and behavioral science, 23(5), pp. 647–657.

- Simple solutions to complex problems fail: “Too often managers are sold simple solutions to complex problems. These simple, quick-fix panaceas fail because they are not holistic or creative enough. They focus on parts of problem situations rather than the whole, they take little account of the interactions between parts, and they pander to the notion that there is one best solution that fits all circumstances.” (p.647)

- Holism as an alternative to reductionism: “Holism has been around for a long time, but because of the apparent success of the traditional scientific method, has had to take second place to reductionism. Holism deserves to be reinstated as an equal and complementary partner to reductionism. It encourages the use of transdisciplinary analogies, it gives attention to both structure and process, it provides a powerful basis for critique, and it enables us to link theory and practice in a learning cycle. As a result there is evidence that holism can help managers make a success of their practice and address broad, strategic issues as well as narrow, technical ones.” (p.647-648)

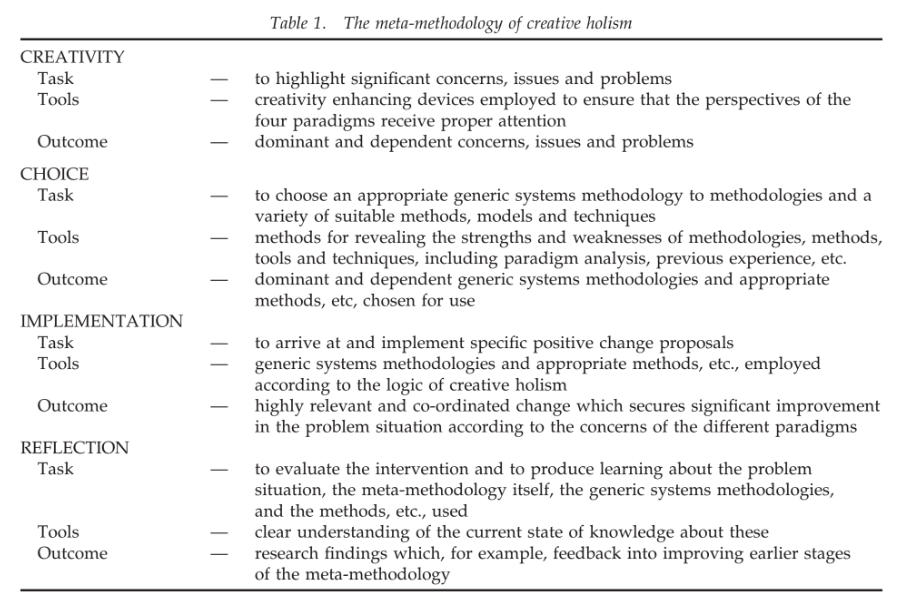

- ‘Creative holism’ has four phases: “Creative holism seeks to be multi-paradigm, multi-methodology and multi-method in orientation. In this way it can provide managers with the joint benefits of holism and creativity so that they can do their jobs better. The four phases of ‘creative holism’—creativity, choice, implementation and reflection—are outlined.” (p.648)

- Turning to consultants often fails: “Faced with increasing complexity, change and diversity, it is not surprising that managers turn to advisers, consultants and academics for help. So desperate have they become for enlightenment that they have elevated a number of these to the status of management gurus. Too often, however, managers have been peddled panaceas in the form of the latest management fad. We are now awash with quick-fix solutions—benchmarking, rightsizing, quality management, process re-engineering, balanced scorecard, knowledge management, customer relationship management, to name but a few. Unfortunately, as so many managers have discovered to the cost of themselves and their organisations, these apparently simple, off-the-shelf solutions rarely work. Fundamentally, they fail because they are not holistic or creative enough (Jackson, 1995; Ackoff, 1999).” (p.649)

- Definition of holism: “Holism puts the study of wholes before that of the parts. It does not, therefore, try to break organisations, or other entities, down into parts in order to understand them and intervene in them. It concentrates its attention instead at the organisational level and on ensuring that the parts are related properly together and are functioning well to serve the purposes of the whole… Today, as the world has grown more complex and it proves impossible or counter-productive to try to break systems down into parts, holism deserves a place as an equal and complementary partner to reductionism. A number of significant benefits emerge for managers if they adopt holistic thinking.” (p.650)

- Order as an emergent property of disorder: “Order is, then, an emergent property of disorder and comes about through self-organising processes operating from within the system itself. Maturana and Varela’s distinction between ‘structure’ and ‘organisation’ adds further insight: Maturana (1986) defining a dynamic composite unity as ‘a composite unity in continuous structural change with conservation of organisation’. In general terms, all the different systems methodologies are able to take advantage of the ability to conceptualise structure and process as interrelated.” (p.650)

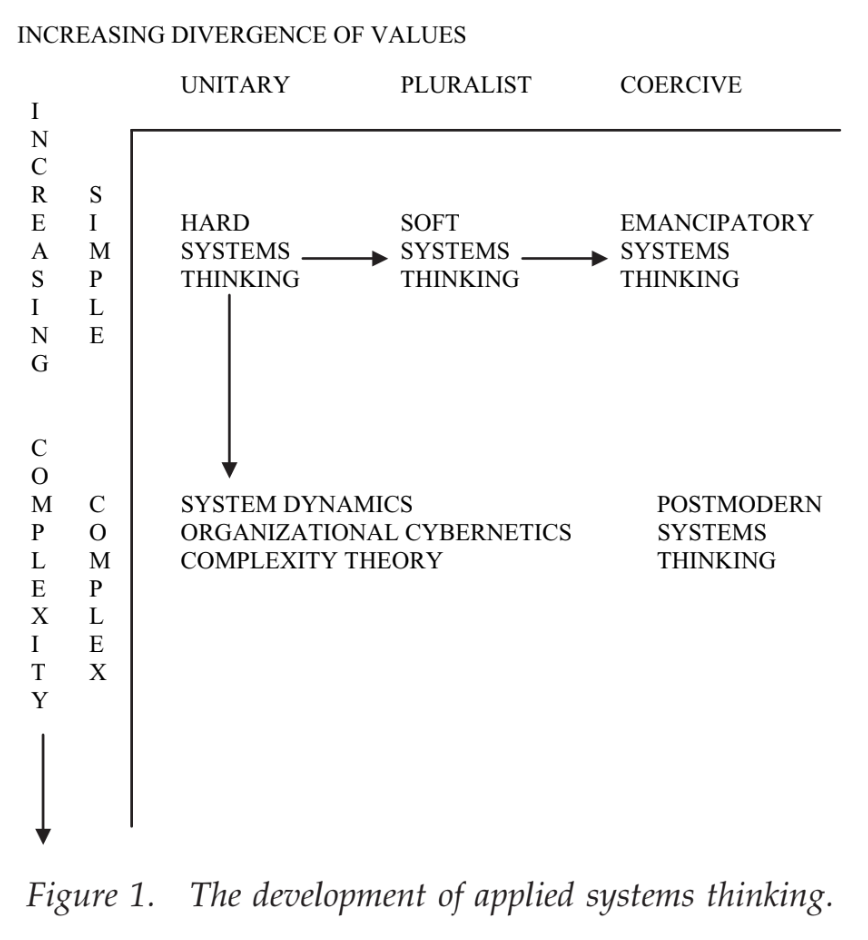

- Development of applied systems thinking: (p.652)

- Other ways of achieving the above: “Figure 1 provides us with a way of seeing developments in applied systems thinking. There are other, equally legitimate tools that can achieve much the same thing— for example, metaphor analysis and paradigm analysis (see Jackson, 2000, 2003).” (p.653)

- Explaining different analyses: “Metaphor analysis sees developments in applied systems thinking as being about the exploration and exploitation of different metaphors closely linked to our understanding of organisations. Hard systems thinking privileges the ‘machine’ metaphor. System dynamics and complexity theory favour the ‘flux and transformation’ metaphor; while organizational cybernetics makes primary use of the ‘organism’ and ‘brain’ metaphors. Soft systems approaches prefer the ‘culture’ and ‘political system’ metaphors; while emancipatory systems thinking entertains the ‘psychic prison’ and ‘instruments of domination’ metaphors. The ‘carnival’ metaphor seems appropriate for postmodern approaches. Carnivals are subversive of order, they allow diversity and creativity to be expressed, they encourage the exceptional to be seen, they are playful and engage people’s emotions.” (p.653)

- Different paradigms: “Developments in applied systems thinking can also be seen as opening up new paradigms to systems thinkers. Hard systems thinking is functionalist/positivist in character; while system dynamics, organizational cybernetics and complexity theory are all functionalist/structuralist. Soft systems thinking is interpretive in nature; while emancipatory and postmodern systems approaches are based on the emancipatory and postmodern sociological paradigms respectively.” (p.653)

- Meta-methodology of creative holism: (p.654)

- Broadest possible approach: “Creative holism suggests that the perspectives of four paradigms— functionalist, interpretive, emancipatory and postmodern—must be considered. In order to achieve this, managers and analysts might explore the paradigms through the use of appropriate metaphors, or employ other creativity enhancing devices. The aim is to take the broadest possible critical look at the problem situation but gradually to focus down on those aspects most crucial to the organisation at this point in its evolution.” (p.654)

- Idea to show progress on four fronts: “‘Reflection’ seeks to judge how successful the intervention has been in bringing about improvement. It does this by taking into account what each paradigm rates as most significant. The functionalist paradigm prioritises goal-seeking and viability, judging in terms of efficiency and efficacy. The interpretive paradigm prioritises exploring purposes by enhancing mutual understanding, judging in terms of effectiveness and elegance. The emancipatory paradigm seeks to ensure fairness, judging in terms of empowerment and emancipation. The postmodern paradigm values the promotion of diversity, judging in terms of exception and emotion. A highly successful intervention should be able to demonstrate progress on all these fronts.” (p.655)

- Critical systems practitioner like a holistic doctor: “I have, elsewhere (Jackson, 2000), compared the critical systems practitioner with a holistic doctor. Confronted by a patient with pains in her stomach, the doctor might initially consider standard explanations, such as over-indulgence, period pains or irritable bowel syndrome. If the patient failed to respond to the usual treatment prescribed on the basis of an initial diagnosis you would expect the doctor to entertain the possibility of some more deep-seated and dangerous malady. The patient might be sent for X-ray, body scan or other tests designed to search for such structural problems. If nothing was found, a thoughtful conversation with the patient might suggest that the pains were a symptom of anxiety and depression. Various forms of counselling or psychological support could be offered. Or, perhaps, a knowledge of the patient’s domestic circumstances, and bruises elsewhere on the body, might reveal that the patient was suffering at the hands of a violent partner. What should the doctor do in these circumstances? Finally, perhaps the patient just needs another interest—such as painting or golf— to take her mind off worries at work.” (p.654)

Korycki, T. (2022)

Korycki, T. (2022) ‘Critical social learning systems – an inquiry, case study and some learning’. Systems and Complexity in Organisation.

Note: this is so close to the requirements for TB872’s EMA that I think it’s potentially a revised submission.

- Uses 14 thematic areas from Blackmore (2010): “Of particular value in this situation are two approaches, the first being critically assessing the situation using landscape ‘themes’ for social learning system praxis (Blackmore, 2010a), which are detailed in Table 1 below, from interview feedback and systems mapping, then reviewed with my colleague to identify gaps between as-is and ought-to-be situations.” (p.3)

- Uses de Laat and Simons’ 2×2: “A second valuable approach relating to social learning systems concerned arriving at an understanding of how people could apply different kinds of learning distinguished by de Laat and Simons (Blackmore, 2010b), to systems and participants in the situation of concern, summarised in Table 2 below:” (p.5)

Kuhn, L. and Woog, R. (2005)

Kuhn, L. and Woog, R. (2005) ‘Vortical postmodern ethnography – introducing a complexity approach to systemic social theorizing.’ Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 22, pp. 139-150.

- Definition of ‘vortical postmodern ethnography’: As the name suggests, vortical postmodern ethnography implicates:

- (1) ethnography—as a research approach to studying and describing human cultural groups;

- (2) postmodernism—as a term describing disillusionment towards the efficacy of totalizing explanations or ‘grand narratives’;

- (3) vorticity—as the characteristic swirling movement of a vortex or whirlpool.

- Vortical postmodern ethnography describes an approach to ethnography that takes as fundamental the swirling or vortical nature of human beings and their processes of existing in social/cultural groupings. A vortical postmodern ethnographic research approach conceptualizes all involved in the research, together with the activities engaged in, not as separate categorical systems (such as researcher and researched), but as swirling interacting parameters. It is further assumed that during the research process vorticity may be stimulated (both inescapably through bringing together cultures and groups not usually brought together, and deliberately, through introducing activities out of the ordinary for participants).” (pp.139-140)

- Human society as emergent: “In complexity terms, human society may be conceived of as spontaneously emerging from a non-linear dynamical system. Physical, social and mental aspects of our human ecology are envisioned as continuously interacting and mutually evoking and evolving.” (pp.141-142)

- Fractal approach: “In applying the concept of fractality to social research, it is necessary to recognize that the fractal relationship selected for study by the researcher is not merely a part of the whole, but that it is representative of the whole. It represents an aspect of the social system that is present at all scales of the system, and which may be examined at certain, chosen scales… While the study of the dynamics and emergence associated with a fractal are representative at all scales, it is recognized that the information obtained is proportional to the scale chosen by the researcher.” (p.142)

- The vortex is an entity of its own: ”In vorticity we see the essential property of complex dynamics exhibited: the ability to self-organize and exhibit unexpected emergent properties. Vorticity may be used to describe the manifestation of emergent properties in the self-organization of systems exhibiting irregular dynamics. The vortex so created is an entity in itself (Dimitrov and Woog, 2002).” (p.143)

- Human sense-making as vortical: “Human sense making in this regard can be described as having a vortical character, where there are streams of communication, ideas, emotions permanently in motion and interacting with each other and exhibiting emergence. In a sense, our discourses evolve from, and are constructed by, those unpredictable (and predictable) dynamics that constitute all human interaction.” (p.143)

- No longer observers vs observed: “All involved in the research, together with the activities engaged in, constitutes the situation under investigation. Object, observer and observation are reconceptualized not as separate categorical systems but as swirling interacting parameters of those systems.” (p.145)

McCarthy, D.D.P., et al. (2011)

McCarthy, D.D.P., et al. (2011) ‘A critical systems approach to social learning- building adaptive capacity in social, ecological, epistemological (SEE) systems’, Ecology and Society, 16(3) 18.

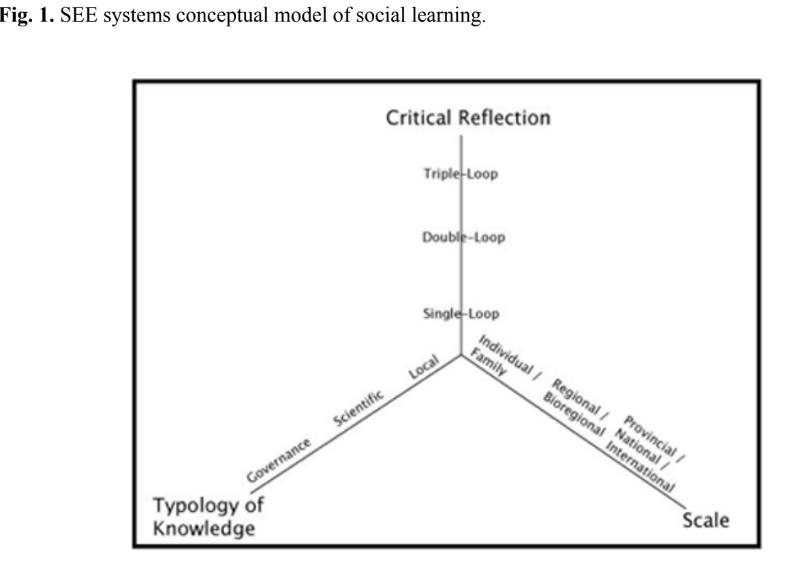

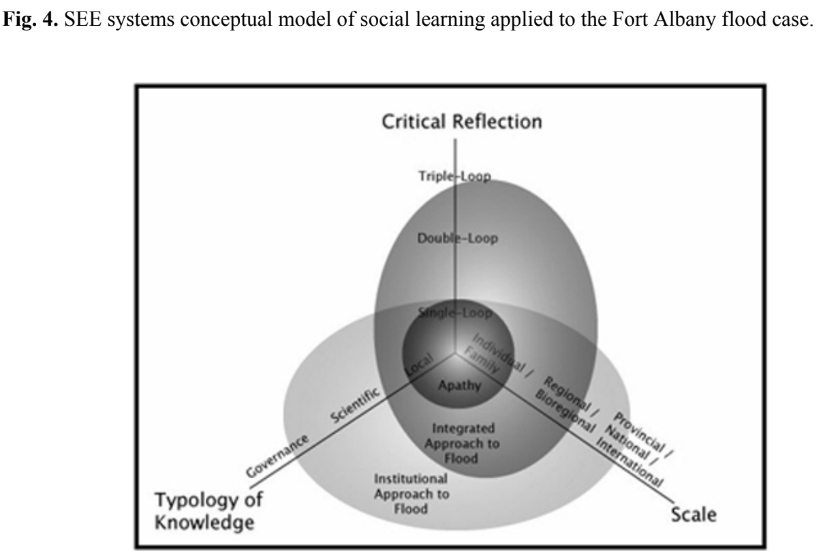

- SEE model with definition of social learning: “[W]e propose the explicit incorporation of knowledge generation and learning into a concept of social–ecological systems or social–ecological-epistemological (SEE) systems… [defining] social learning as an on-going, adaptive process of knowledge creation that is scaled-up from individuals though social interactions fostered by critical reflection and the synthesis of a variety of knowledge types that result in changes to social structures (e.g., organizational mandates, policies, social norms).” (p.2)

- Three types of knowledge: “[L]earning occurs in dynamic tension among three types of knowledge, “episteme,” “techne,” and “phronesis,” originally articulated by Aristotle and then interpreted by Flyvbjerg (2001) to provide a new rationale for social science. “Episteme” is based on general analytical rationality and is intended to be universal, invariable, and context independent (Flyvbjerg 2001) and is reinterpreted in this work as scientific (“episteme”), local (“techne”), and governance (“phronesis”). Modern equivalents of the original Aristotelian term include “epistemology” and “epistemic.” “Techne” is based on instrumental rationality and is

pragmatic, variable, and context dependent (Flyvbjerg 2001). The original concept appears today in terms such as “technique,” “technical,”and “technology.” Finally, the third Aristotelian type of knowledge “phronesis,” interestingly, has no contemporary equivalent. “Phronesis” is based on ethical, practical value rationality. It is pragmatic, variable, and context dependent and involves deliberation about values with reference to practical application of theory (praxis; Flyvberg, 2001). Flyvberg (2001) argued that instead of social science attempting to develop “episteme” as the natural sciences do, it is more appropriate for the social sciences to attempt to develop “phronetic” knowledge.” (p.3)

- Triple loop learning: “Flood and Romm (1996: xi) describe three centers of learning associated with the three loops that represent very different questions. The first center or loop of learning asks “Are we doing things right?” The second center or loop questions the goals or assumptions of the first loop by asking “Are we doing the right things?” The third center or loop, which represents the innovative contribution to the organizational or social learning literature, asks if “power structures are acting too much in support of definitions of “rightness” or conversely if any presumed ‘right way’ is becoming too forceful? “ This triple-loop view of social or organizational learning explicitly integrates notions of power and sets learning in a social or political context.” (p.3)

- Different scales of learning: “Based on insights from the work of Giddens (1984) structuration theory, the third axis highlights the dialectic relationship between individuals and the creation of social structures through repeated behaviors and rule systems. According to Giddens (1984), social structures such as rules, laws, regimes, and institutions emerge out of an individual agent’s behavior and an individual agent’s behavior is constrained by the rules and structures that emerge over time.” (p.4)

- Diagram of SEE model: (p.4)

- Example of SEE model: (p.10)

Stephens, A., Jacobson, C. and King, C. (2010)

Stephens, A., Jacobson, C. and King, C. (2010) `Describing a feminist-systems theory’, Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 27(5), pp. 553–566.

- Definition of FST: “[Feminist Systems Theory] is political and calls for explicit challenges to ideology that sustain power and privilege imbalance. The goal is to emancipate collectives, individuals and ecologies from injustices and exclusions.” (p.553)

- Central themes of Critical Systems Theory: “CST does now appear to reside upon three central themes:

- (1) undertake deliberate action towards social improvement,

- (2) engender emancipation or liberation from oppression, with a commitment to achieving mutual understandings and

- (3) addressing issues of power and coercion in research practice (Oliga, 1995; Midgley, 1996b, 2000; Hammond, 2003). (p.555)

- Other ways of knowing: “Conventional scientific methods should no longer be privileged as universal and guarantors of truth (Angen, 2000). It must no longer be regarded as the only way to approach inquiry. A critique of positivism and its assumptions expressed in scientific research, however, should not be interpreted as ‘an attack’ (Ravetz, 1999), rather as an assistance.” (p.559)

- FST extends notion of boundary critique: “FST extends King (2000) and Midgley’s (2000) notion of boundary critique. Accounts of the self, relative to the boundaries of others, enables agents to reject harmful dualisms and keep the independence or distinguishability of others. To re-examine and reconceptualize the dualistically construed categories themselves, is a reflection upon the arbitrarily constructed boundaries around our social and personal knowledge domains. This principle urges thinkers to reveal interwoven and connected philosophical categories built on exclusions of women, nature and subordinated non-humans, making visible hidden political dimensions.” (p.560)

- Interpretivist notion of validity: “FST can adopt an interpretivist notion of validity. Positivist expectations of objectivity render ‘rigour’ a poor instrument for evaluating interpretivist research. Rethinking rigour involves developing purposeful research criteria that reflects qualities of responsibility, accountability, partiality and subjectivity (Davies and Dodd, 2002). A legitimate research effort will demonstrate its quality and worth in terms of purposeful criteria, determined by the researcher’s relationship with the contexts in which they are embedded.” (p.561)

- Boundary critique & marginalisation: “A boundary critique is important in determining the extent of the problem, and to identify interests which are marginalized, so as to include them (Hector et al., 2009)” (p.562)

- Benefits of Feminist Systems Theory approach: “FST by embedding the soft systems definition of sustainability into a more expansive framework, gives researchers the space to ask deeper questions, to ensure that their work within the social and environmental realms move beyond a superficial or inadequate notion of sustainability.” (p.564)

Vickers VC, Sir G. (1972)

Vickers VC, Sir G. (1972) ‘The Management of Conflict.’ Futures, 4(2), pp. 126-141.

- Three kinds of constraint: “The three kinds of constraint which I have described are reflected in three familiar verbs. What we can and cannot do, must and must not do, ought and ought not to do are defined by the constraints imposed on us by circumstances, by other people and by ourselves. Each of these constraints can raise conflicts. Each conflicts with the others. And any or all of them may conflict with that simpler category, what we want and do not want to do.” (p.130)

- Three different reasons for conflict: “It is useful also to distinguish conflictual situations according to what the conflict is about. Three types can be distinguished, though they are always found in combination.

- The type least easy to recognise and hardest to resolve involves conflict about what the situation shall be deemed to be.” (p.132)

- Conflicts due to definitional differences: “All major conflicts involve differences in the values which different parties attach to different aspects of a situation common to them all, differences which often lead them to different definitions of the situation itself.” (p.132)

- The membership factor: “Persons in conflict, whatever divides them, are usually also related through common membership of one or more systems; and this may impose on them some restraints and give them some assurances which they would not otherwise feel. This factor is of very great importance both to the resolution and to the containment of conflict. I refer to it as the constraints and assurances of membership or for brevity, as the membership factor.” (p.134)

- Constraints of membership: “The constraints of membership stem from those three sources which are also the source of our conflicts. They may arise from an objective appreciation of a common situation. Men at sea, for example, even when in open mutiny, may remain aware of their common dependence on the ship and, in extreme danger, may abate their conflicts sufficiently to co-operate in keeping it afloat.” (p.134)

- Power of the membership factor: “This, the membership factor, operates with very varying degrees of potency in human systems of different types and sizes, and even in the same system at different periods in its history. It is normally far more potent in small systems united by a common objective, such as a team of explorers or even a professional partnership, than in a diffuse political society or even a large business corporation. However strong or weak, it improves the system’s capacity to resolve and contain conflict in at least three ways. Insofar as it makes the operation of rule and role acceptable, it mutes potential conflict so that it scarcely arises. At the other extreme, it helps to contain even the fiercest conflict by reinforcing whatever sanctions authority commands. For dissenters cannot rebel against any specific decision without challenging the system as a whole and awakening the opposition of all who feel protected by it. Moreover, the would-be rebel cannot pursue his rebellion without putting himself out of membership of his society, redefining his former fellow members as aliens or enemies and correspondingly redefining himself and the whole system of his self- and mutual expectations. The stronger his sense of membership, the more reluctant will he be to restructure himself so radically. Thus, the system of self- and mutual expectations from which these constraints and assurances proceed is powerful to sustain itself and therewith the social system that depends on it.” (p.138)

Potentially-relevant further reading

As mentioned at the start of this post, while I was reading the above, I came across some further reading which may be relevant:

- Bandura, A. (1971) Social learning theory: motivational trends in society. Morristown, New York: General Learning Press.

- Bawden, R.J. (1995) ‘I as in academy: Learning to be systemic.’ Systems Research, 12, pp. 229–238.

- Boulton, G. and Lucas, C. (2008) What are universities for? [Online]. Available at: https://www.leru.org/files/What-are-Universities-for-Full-paper.pdf

- Flood, R.L. (1995) ‘What is happening when you problem solve? A critical systems perspective.’ Systemic Practice and Action Research, 8, pp. 215–221.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2001) Making social science matter: why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Giddens, A. (1994) Risk, Trust, Reflexivity. In: Beck, U., Giddens, A. and Lash, S. (eds.) Reflexive Modernization: Politics, tradition and aesthetics in the modern social order. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

- Ison, R.L. (1999) ‘Editorial: Applying systems thinking to higher education.’ Systems Research & Behavioural Science, 16(2), pp. 107–112.

- Jackson, M.C. (1982) ‘The Nature of Soft Systems Thinking: The work of Churchman, Ackoff and Checkland.’ Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 9, pp. 17–29.

- Jackson, M.C. and Keys, P. (1984) ‘Towards a system of systems methodologies.’ JORS, 35, pp. 473–486.

- Keen, M., Brown, V.A. and Dyball, R. (2005) Social learning in environmental management: towards a sustainable future. London: EarthScan.

- Krippendorff, K. (1993) ‘Major metaphors of communication and some constructivist reflections on their use.’ Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 2(1), pp. 3–25.

- Kuhn, L. (2002) ‘Complexity, cybernetics and human knowing.’ Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 9(1), pp. 39–50.

- Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980) Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Maturana, H.R. (1988) ‘Reality: the search for objectivity or the quest for a compelling argument.’ Irish Journal of Psychology, 9, pp. 25–82.

- Maturana, H.R. and Varela, F.J. (1987) The Tree of Knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding. Boston: Shambhala.

- McClintock, D., Ison, R.L. and Armson, R. (2004) ‘Conceptual metaphors: A review with implications for human understandings and systems practice.’ Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 11(1), pp. 25–47.

- Midgley, G. (1997) ‘Mixing methods: Developing systemic intervention.’ In: Mingers, J. and Gill, A. (eds.) Multimethodology: The Theory and Practice of Combining Management Science Methodologies. Chichester: Wiley, pp. 291–332.

- Midgley, G. (2000) Systemic intervention. Boston, MA: Springer US (Contemporary Systems Thinking).

- Midgley, G. (1996b) ‘What is this thing called CST?’ In: Flood, L.R. and Romm, N.R.A. (eds.) Critical Systems Thinking: Current Research and Practice. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 11–22.

- Mingers, J.C. (1980) ‘Towards an appropriate social theory for applied systems thinking.’ Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 7, pp. 41–50.

- Russell, D.B. (1986) How we see the world determines what we do in the world: preparing the ground for action research. Richmond: University of Western Sydney (Hawkesbury).

- Salner, M. (1986) ‘Adult cognitive and epistemological development.’ Systems Research, 2, pp. 225–232.

- Shen, C.Y. and Midgley, G. (2007) ‘Toward a buddhist systems methodology 1: comparisons between buddhism and systems theory.’ Systems Practice and Action Research, 20, pp. 167–194.

- Weick, K.E. (1995) Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Wynne, B. (1996) ‘May the Sheep Safely Graze? A Reflexive View of the Expert-Lay Knowledge Divide.’ In: Lash, S., Szerszynski, B. and Wynne, B. (eds.) Risk, Environment and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology. London: Sage Publications.

Image: DALL-E 3