I’m in London today at the Guardian Innovation in Education event (hashtag #IIE2011). Not only will it be the first time I’ve been on a keynote panel but I’ll also be chairing a session for the first time. Happy days.

The following are those currently listed as joining me on the keynote panel (which has been shuffled more often that a Tory Cabinet):

I’ll be given a couple of minutes to outline my position on innovation and, bizarrely, learning styles. The latter is a non-starter as far as I’m concerned given my experience in the classroom and this devastating critique on YouTube by Prof. Daniel Willingham. But innovation? I’ve definitely got a couple of things to say about that.

1. Innovation is predicated upon standardisation

Homogeneity in ecological terms, refers to a reduction in biodiversity. I think it’s important to make it clear at the outset that’s not what I mean when I’m talking about standardisation. What I mean by standardisation is a common, negotiated base upon which something can be constructed. This base could be a technology, it could be a set of practices, a calendar, defined workflows or communications channels.

Something I would change if I could go back and re-teach my early career would be the way that I approached innovation. In my current position at JISC infoNet and in my previous role as Director of e-Learning I’ve seen just how important the social negotiation and co-construction of a common baseline is. To mix metaphors, it’s about getting people on the same page and facing the same direction. Too often in my early career I went full-tilt in a different direction to others, thinking to myself that I could bring others onboard I’d reached ‘version 1.0’. Now I realise the importance of bringing in people much earlier than that.

Whilst it is may be possible to enforce standardisation in a top-down manner, effective leaders know that this is unlikely to encourage buy-in. As I argued in Chapter 10 of my thesis on digital literacies the process is at least as important as the outcome. Conversation and iteration is important because the very nature of innovation means that you don’t know necessarily know what’s going to happen next. As Woodrow Wilson famously stated, “I not only use all the brains that I have, but all that I can borrow”.

Douglas Adams was being flippant when he called for “rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty” but, when it comes to innovation, demarcating such areas can be productive. Be focused. If, for example, your organisation is focusing upon methods of communication, getting sidetracked by existing problems (such as software incompatibilities) or irrelevancies (the staff dress code) is likely to be unhelpful. Get things right one at a time building towards a bigger picture. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

2. Sustaining and embedding innovation

In JISC’s Sustaining and Embedding Innovations: a good practice guide, Peter Chatterton defines three broad stages of innovation:

- Invention (generation of new ideas)

- Early Innovation (practical implementation of new inventions, usually in specific areas)

- Systemic Innovation (organisation or institution-wide adoption of inventions)

As colleague Andrew Stewart and I argued at the Future of Technology of Education conference the problem is that we get stuck at the second step. The reason for this is twofold, I believe.

Firstly, we’ve outsourced technological invention to the market. This means that early innovation (usually) involves taking something not designed explicitly with education in mind and finding way of using it for pedagogical purposes. By the time we’ve done that, of course, the market moved on and the process begins all over again. We’re like dogs chasing shiny cars.

The second reason, however, is due to education being a political football. Every year a raft of changes are enforced upon educational institutions, and schools in particular. Somtimes (and I’m looking at you, Michael Gove, with the English Baccalaureate) such changes are even made half-way through a school year! As a result, systemic innovation and ownership of the change process by overworked, underpaid staff is extremely difficult to achieve, even if they believe in the changes proposed. Some schools, such as Cramlington Learning Village manage focused, systemic change but these are few and far between.

Conclusion

Innovation is a tricky beast. You’re never quite sure when or where the next great idea will come from. There are, however, some ways to tame the monster. Here’s my three suggestions:

- Focus on workflows: huge efficiencies can be gained by socially-negotiating these and using them as a standardised basis. In one school I used to work at, these were posted in every classroom for sanctions, rewards, book marking, everything. Review these often so they don’t become burdensome when the contexts change due to wider environmental factors.

- Take a step back: as someone (hilariously) mentioned at a JISC programme startup meeting this week, “the early bird may get the worm, but it’s the second mouse that gets the cheese.” Make sure that everyone knows what they are there for. Have a discussion about the purpose(s) of education, if necessary.

- Get everyone involved: when I say that you don’t know where the next transformational idea may come from, I’m serious. Get as many different angles on the problem as possible. And even when things are going well, have channels and methods of communication that allow people to make leftfield suggestions without being ridiculed.

What are YOUR thoughts on innovation in education?

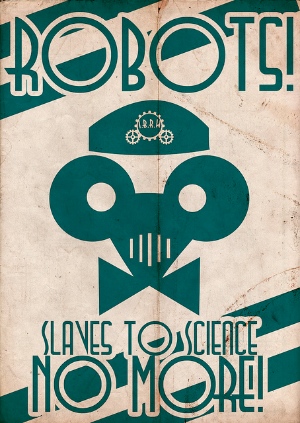

Almost every sci-fi film you will ever see will feature some kind of robot. In some of these robots can be a force for good (

Almost every sci-fi film you will ever see will feature some kind of robot. In some of these robots can be a force for good (