TB871: Supporting the development of others

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Understanding how people learn is a complex business. As an educator, though, it’s a crucial underpinning to be able to do your job. Learners can progress through various stages of cognitive and ethical development, with one model presented in the module materials as Knefelkamp’s Four Development Instructional Variables (The Open University, 2020).

Knefelkamp’s work was based on the work of William G. Perry, whose framework outlines a sequence of positions through which learners progress as they develop cognitively and ethically. These positions range from a simplistic, dualistic understanding of the world to a more complex, relativistic view where learners make commitments in a contextual world.

The key positions include:

- Position 1: Basic Dualism: Absolute thinking, reliance on authorities.

- Position 2: Multiplicity Pre-legitimate: Beginning to see multiple viewpoints.

- Position 3: Multiplicity Legitimate but Subordinate: Recognizes multiple viewpoints but relies on authority for correctness.

- Position 4: Multiplicity Legitimate: Accepts multiple viewpoints as legitimate.

- Position 5: Relativism: Understands that knowledge is contextual and relative.

- Positions 6-9: Commitment in Relativism: Integrates personal values with learning, making commitments in a relativistic world.

Knefelkamp’s four variables are, as far as I understand, Positions 2-5.

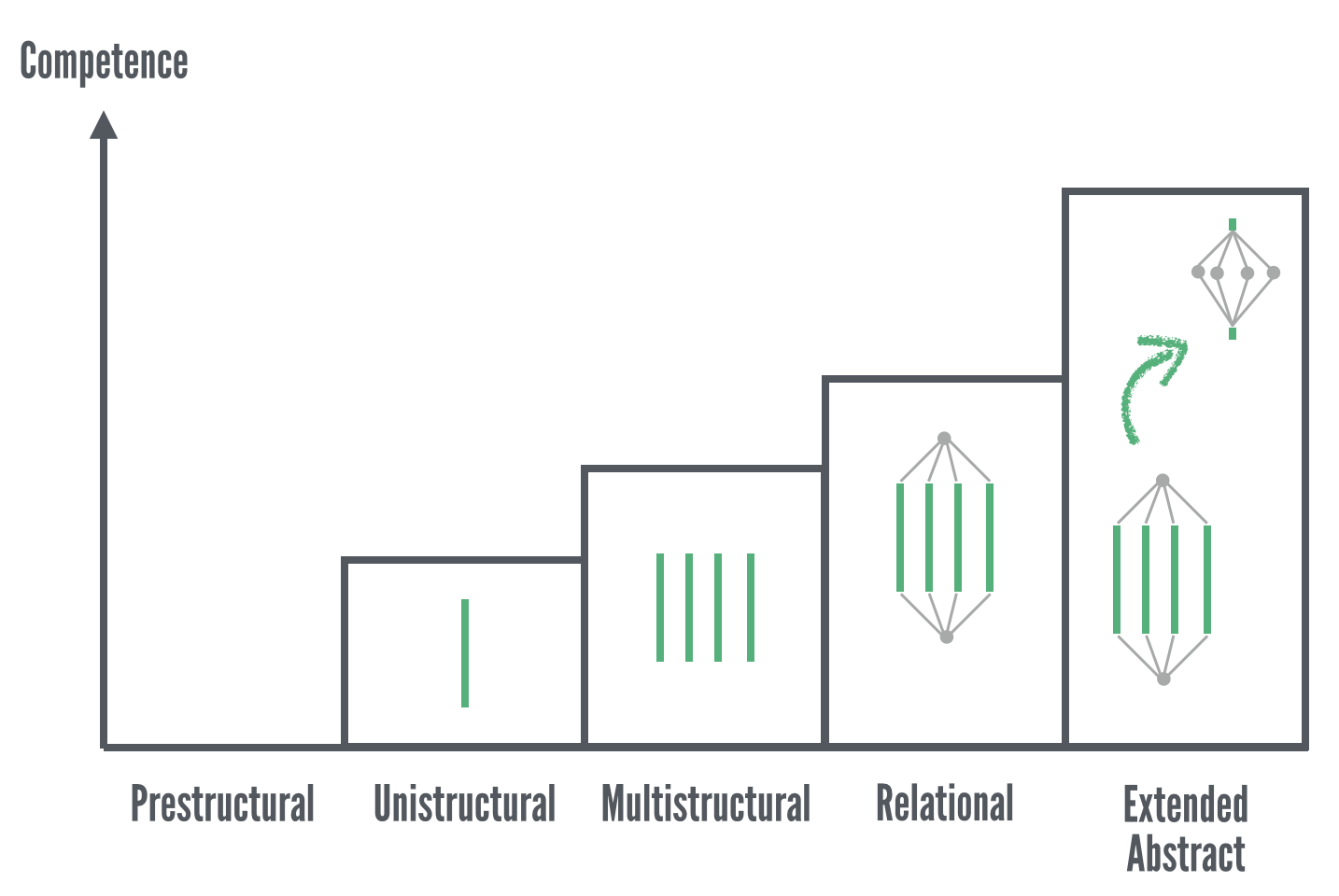

This struck me as being rather similar to the Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes (SOLO) Taxonomy developed by John Biggs and Kevin Collis, which I’ve used extensively in my career. In fact, I created the image below, which is used on the Wikipedia page for the topic.

The SOLO Taxonomy describes levels of increasing complexity in learners’ understanding. The taxonomy consists of five levels:

- Pre-structural: Lack of understanding, irrelevant responses.

- Uni-structural: Focus on one relevant aspect.

- Multi-structural: Focus on several relevant aspects independently.

- Relational: Integration of multiple aspects into a coherent whole.

- Extended Abstract: Abstract and generalised understanding, application to new areas.

Both Perry’s framework and the SOLO taxonomy describe a developmental progression from simple, dualistic thinking to complex, integrated understanding. They emphasise the need to adjust educational strategies to the learner’s developmental stage, providing more structure and guidance at earlier stages and promoting independence and critical thinking at advanced stages.

Mapping Perry’s Framework to SOLO Taxonomy

| Perry’s Framework | SOLO Taxonomy | Characteristics | Educational Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position 1: Basic Dualism | Pre-structural | Absolute thinking, reliance on authorities | High structure, clear guidance, simple and direct feedback |

| Position 2: Multiplicity Pre-legitimate | Uni-structural | Beginning to see multiple viewpoints | Structured support, introduction to diverse perspectives, controlled experiential learning |

| Position 3: Multiplicity Legitimate but Subordinate | Multi-structural | Recognizes multiple viewpoints but relies on authority for correctness | More information, additive learning, structured exploration |

| Position 4: Multiplicity Legitimate | Relational | Accepts multiple viewpoints as legitimate | Moderate structure, encouragement of connections, diverse perspectives |

| Position 5: Relativism | Extended Abstract | Understands that knowledge is contextual and relative | Low structure, high autonomy, encouragement of abstract thinking, real-world applications |

| Positions 6-9: Commitment in Relativism | Extended Abstract | Integrates personal values with learning, making commitments in a relativistic world | Minimal structure, high autonomy, diverse and abstract concepts, facilitation of deep personal engagement |

Any kind of well-researched developmental framework can help educators design effective learning experiences that cater to the needs of learners at different stages. By aligning educational strategies with the developmental levels described by Perry and the SOLO Taxonomy, educators can better support the cognitive and ethical growth of their students. I think I prefer SOLO, because I’m more familiar with it, but I’m interested in further exploring the ethical dimension of Perry’s framework.

References

- The Open University (2020) ‘P4.2.5 Taking responsibility for your own learning, TB871 Block 4 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261494§ion=3.5 (Accessed 25 July 2024).