TB871: A deeper dive into OCEAN

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

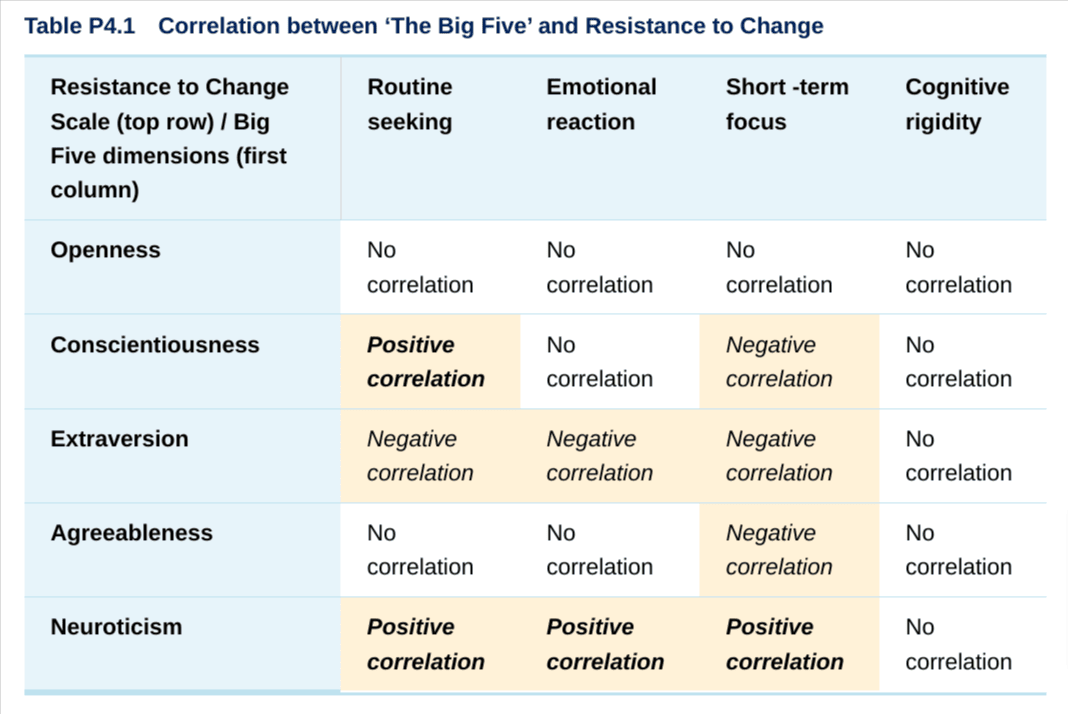

As I introduced in a previous post, the OCEAN model presents a way of understanding personality through the traits of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Profiling people using this model can help provide insights into both personal and interpersonal dynamics, which can be helpful in strategic contexts involving uncertainty, diverse perspectives, and undefined boundaries.

The idea is that profiling yourself and others using the OCEAN model enhances self-awareness and understanding of others. This is particularly helpful with communication, as appreciating different perspectives and working styles, helps create a better working environment. For example, I’ve said many times in person and on this blog that the Belbin feedback I received showed a difference between how I was perceived by the team who worked in the same office as me, compared with those who worked at other institutions. By appending smiley emoji to my emails, I altered how those external colleagues considered the ‘tone’ I was taking with them.

Profiling team members can also help in creating balanced teams. A mix of traits, for example combining highly conscientious individuals with those high in openness, encourages both detailed planning and creative problem-solving. Understanding personality traits may be valuable in resolving conflicts, too, as it provides insights into how people react differently in stressful situations. As a result, we can use a range of strategies to manage differences constructively.

When dealing with strategy, especially in unpredictable environments, team profiling helps anticipate responses to uncertainty. Individuals who are high in ‘openness’ (like me!) may thrive in ambiguous situations, exploring novel solutions. Individuals with high ‘agreeableness’ may excel in finding common ground, while those with high extraversion could advocate for specific viewpoints effectively. Traits such as openness and conscientiousness also influence perceptions of boundaries: those high in openness may push for broader scopes, while those high in conscientiousness focus on clear, manageable limits.

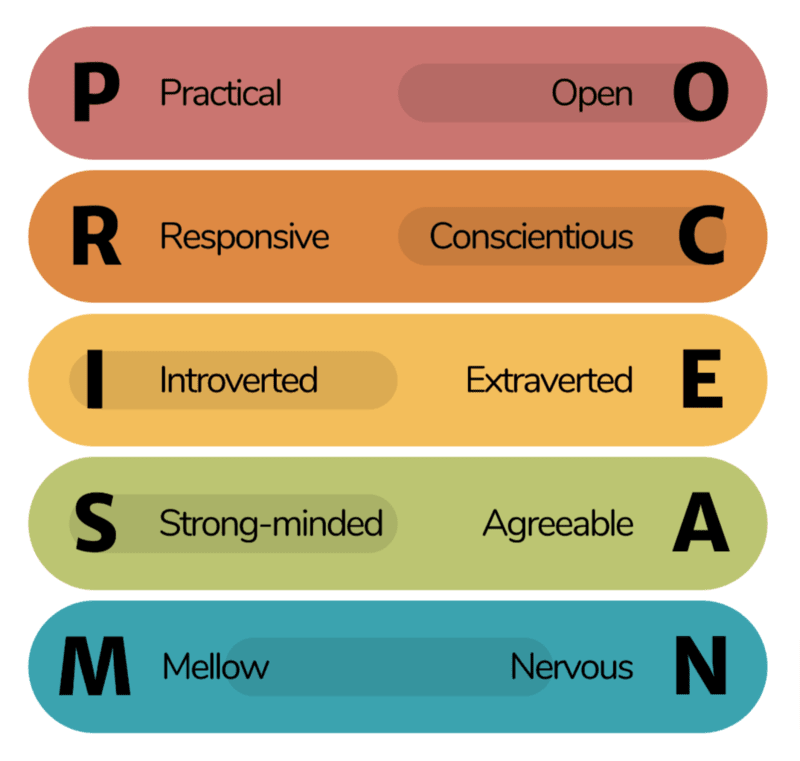

Reflecting on my own results from the PRISM-OCEAN test, I found that I am characterised as:

- Open (curious, creative)

- Conscientious (organised, disciplined)

- Introverted (low key, reserved)

- Strong-minded (competitive, sceptical)

- Moderate (mellow, nervous)

These traits no doubt influence my approach to systems thinking and strategy making:

- Openness: My curiosity and creativity mean I’m naturally drawn to explore the holistic and integrative aspects of systems thinking. This trait enables me to embrace diverse perspectives and novel ideas, which are important in dealing with complex and uncertain environments.

- Conscientiousness: My organisational skills and disciplined nature ensure that my strategic plans are well-structured and considered. This trait helps balance the broad exploration encouraged by openness with more detailed, methodical planning.

- Introversion: As someone reserved and low key, I might prefer reflecting on issues internally before engaging in discussions. Indeed, I prefer writing to figure out what I think than discussing things with others. This introspective approach potentially leads to deeper insights and more thoughtful contributions when collaborating with others.

- Strong-mindedness: My competitive and sceptical nature drives me to critically evaluate different strategies and viewpoints. This trait is seen as a character defect by some, but I think it can be valuable in identifying potential flaws and ensuring sound decision-making processes.

- Moderate Neuroticism: Being ‘mellow’ yet occasionally ‘nervous’ helps me stay calm under pressure while being aware of potential risks. This balance is achieved by managing stress effectively and organising my life and thoughts so that I can maintain focus during strategic planning.

It’s obvious but true that different individuals perceive situations differently. A risk analyst is usually someone who is detail-oriented and methodical, and may find structured environments comforting. Conversely, a tradesperson, accustomed to a more dynamic approach problem-solving, might prefer less structured settings. Such personality traits influence one’s approach to systems thinking, as high openness may naturally align with systems thinking’s holistic nature, while high conscientiousness might focus on detailed, methodical aspects (aka more ‘systematic’ approaches).

The metaphor used in the module materials (The Open University, 2020) is of systems thinking encouraging broader perspectives, similar to widening a ‘torch beam.’ High openness may facilitate this process, whereas high conscientiousness might require balancing detailed analysis with broader views. As familiarity with systems methodologies grows, what once seemed ‘dark’ may become more manageable.

Profiling using the OCEAN model potentially provides useful insights into human behaviour, which in turn helps us with effective strategy making in complex environments. Reflecting on the personality traits of ourselves and others within the context of systems thinking enhances our strategic capabilities. This can aid in the integration of diverse perspectives and management of uncertainty.

References

- The Open University (2020) ‘Levels and patterns in personality?’, TB871 Block 4 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261494§ion=2.1.3 (Accessed 25 July 2024).

Image: USGS