TB872: The juggler isophor for systems practice

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

An ‘isophor’ is different to a metaphor. Coined by Humberto Maturana, the idea is that instead of sparking the imagination, it focuses our attention:

The notion of metaphor invites understanding something by proposing an evocative image of a different process in a different domain (e.g., politics as war). With the metaphor you liberate the imagination of the listener by inviting him or her to go to a different domain and follow his or her emotioning. When I proposed the notion of isophor… I wanted it to refer to a proposition that takes you to another case of the same kind (in terms of relational dynamics) in another domain. So, with an isophor you would not liberate the imagination of the listener but you would focus his or her attention on the configuration of processes or relations that you want to grasp. In these circumstances, the fact that a juggler puts his or her attention on the locality of the movement of one ball as he or she plays with them, knowing how to move at every instant in relation to all the other balls, shows that the whole matrix of relations and movements of the constellation of balls is accessible to him or her all the time. So, juggling is an isophor of the vision that one must have of the operational-relational matrix in which something occurs to be able to honestly claim that one understands it. That is, juggling is an isophor of the vision that one wants to have to claim that one understands, for example, a biological or a cultural happening (such as effective system practice)

Maturana, H. quoted in Ison, R. (2017) Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. p.61. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

So to summarise:

- Metaphors — help us understand one thing by comparing it to something quite different (e.g. “politics is war”). Involve the use of imagination to think about things in a new way.

- Isophors — compare two things that are similar in how they relate or work, but are in different areas. Focus our attention on understanding the patterns and relationships involved.

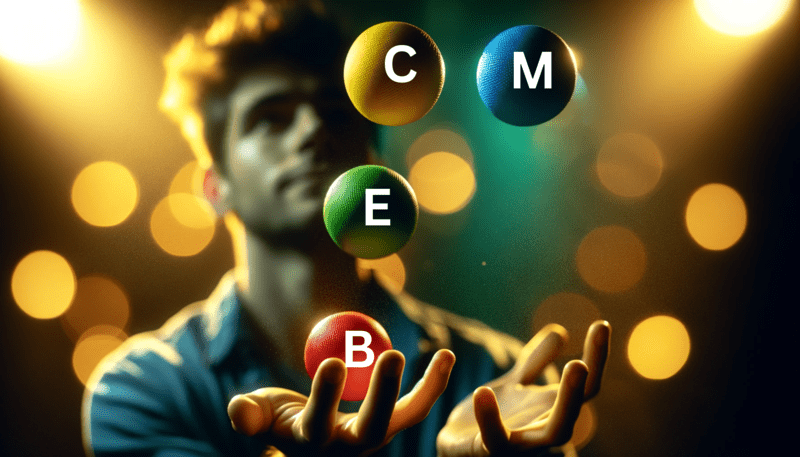

The example given in Chapter 4 of Ison’s book Systems Practice: How to Act is of a juggler who is juggling four balls:

The isophor of a juggler keeping the four balls in the air is a way to think about what I do when I try to be effective in my own practice. It matches with my experience: it takes concentration and skills to do it well. But all isophors, just like metaphors, conceal or obscure some features of experience, while calling other features to attention. The juggler isophor obscures that the four elements of effective practice are related. I cannot juggle them as if they were independent of each other. I can imagine them interacting with each other through gravitational attraction even when they are up in the air. Further, the juggler can juggle them differently, for example tossing the E ball with the left hand and the B ball with the right hand. These visualisations allow me to say that, in effective practice, the movements of the balls are not only interdependent but also dependent on my actions. Also, when juggling you really only touch one ball at a time, give it a suitable trajectory so that you will be able to return to it while you touch another ball. So it’s the way attention has to go among the various domains, a responsible moment of involvement that creates the conditions for continuance of practice.

Ison, R. ibid. p.60.

Those four balls, as illustrated in the image at the top of this post, are:

- Being (B-ball): concerns the practitioner’s self-awareness and ethics. Involves understanding one’s background, experiences, and prejudices (so awareness of self in relation to the task and context is crucial).

- Engaging (E-ball): concerns engaging with real-world situations. Involves the practitioner’s choices in orientation and approach, affecting how the situation is experienced.

- Context (C-ball): concerns how systems practitioners contextualise specific approaches in real-world situations. Involves understanding the relationship between a systems approach and its application, going beyond merely choosing a method.

- Managing (M-ball): concerns the overall performance of juggling and effecting desired change. Involves co-managing oneself and the situation, adapting over time to changes in the situation, approach, and the practitioner’s own development.

Thinking about the isophor of juggling in relation to my own life and practice is quite illuminating. It’s certainly relevant to parenting, where everything always seems to be a trade-off, but as I promised to focus mainly on professional situations in my reflections for this module, I’ll instead relate this to my work through WAO.

🔴 Being (B-ball)

At our co-op, we believe in living our values and in approaches such as nonviolent communication. Some of this is captured on this wiki page. As an individual member of WAO, I need to understand why I act (and interact) in a particular way in different contexts. This relates to my colleagues, clients, and members of networks of which I’m part.

We also need to think about the way that we as an organisation interact with one another and with other individuals and organisations. We’re interested in responsible and sustainable approaches, so ethics are particularly important to us. (A good example of this is the recent Substack drama.)

🟢 Engaging (E-ball)

There is always a choice in terms of how to engage with a situation, and every client is different. There are plenty of individual consultants and agencies who take a templated, one-size-fits-none approach to situations. But while we learn from our experiences and previous projects, we try to engage based on the specific context.

Client environments can be complex, as there are all kind of pressures and interactions of which we are not always aware. For example, a CEO being under pressure from their board, or an employee being at risk of redundancy can massively change their behaviour. Having tried and failed to change something previously can lead to cynicism or malaise.

Equally, finding the right ‘leverage points’ within an organisation or network can be incredibly fruitful. Success tends to breed success (in terms of validation) and changes most people’s conceptualisation of the situation.

🟡 Context (C-ball)

A lot of ‘systems thinking’ approaches that I see on LinkedIn are simply people taking templates and trying to apply them to a particular situation. While this is part of systems thinking, contextualisation means deploying one or more of a range of techniques.

Some of this involves crafting approaches which resonate with the client’s culture and objectives. For example, there are ‘messy’ clients, ones that thrive in a slightly chaotic environment. They prize relationships over things looking shiny. Conversely, there are those where every slide deck must look polished and interactions are more formal.

What I remind myself (and others that I work with) is that when we’re working for a client, we’re often working for their boss. That is to say, unless we’re working directly with the person who signs off the budget, we need to produce things that fit with how the person holding the purse strings sees the organisation. That perception can change over time, but it can’t be done immediately. Sometimes there has to be an element of smoke-and-mirrors to give space to get the real work done under the guise of something else.

🔵 Managing (M-ball)

Situations change over time. Particularly when working with longer-term clients, it’s important to take a moment and ensure that the strategies we’re using mesh with current realities. For example, as Heraclitus famously said, we can’t step into the same river twice. The way that I understand this enigmatic quotation is that this is because the river has changed and we have changed.

This is why retrospectives and planning sessions are important. Simply allowing a project to float along without them means that the dynamics of the project aren’t being addressed from either our side or the client side. This can include everything from increasing our day rates due to the cost of living going up, to the client pivoting their strategy and neglecting to tell us.

Sometimes, this might mean bringing in different skills, approaches, or expertise to the project. After all, meaningful and sustainable change doesn’t happen simply by doing the same things on repeat. To bring it back to parenting, we don’t treat kids the same way as teenagers as they are as toddlers.

This isophor of the juggler underpins a lot of the rest of Ison’s book, and will inform the next assessment I do as part of this module. So you’ll be coming across it again in future posts!

Image: DALL-E 3