TB872: What I talk about when I talk about juggling

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

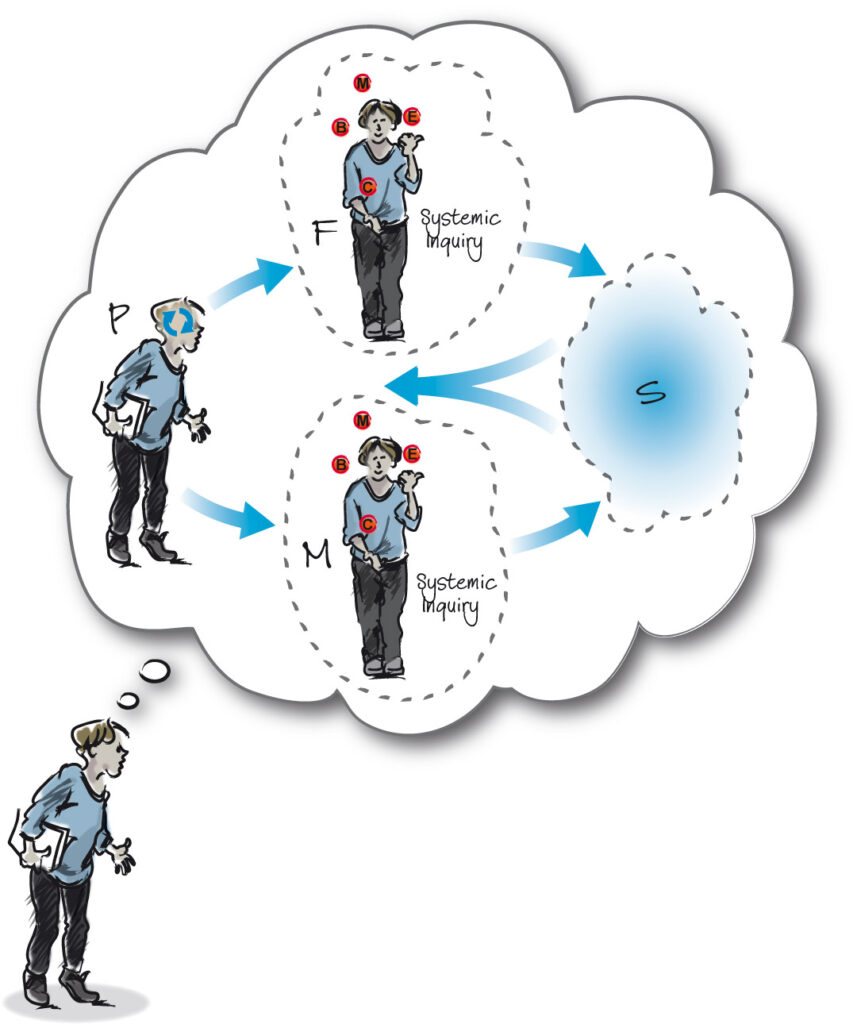

I’m new to the juggler isophor which is introduced in Systems Practice: How to Act. While I attempted to apply it to the work of Donella Meadows in a recent post, I haven’t discussed in much detail how each of the BECM balls ‘manifest’ in different areas of my life. Hence this post.

As a reminder, an isophor is different to a metaphor:

- Metaphors — help us understand one thing by comparing it to something quite different (e.g. “politics is war”). Involve the use of imagination to think about things in a new way.

- Isophors — compare two things that are similar in how they relate or work, but are in different areas. Focus our attention on understanding the patterns and relationships involved.

The four balls are:

- Being (B-ball): concerns the practitioner’s self-awareness and ethics. Involves understanding one’s background, experiences, and prejudices (so awareness of self in relation to the task and context is crucial).

- Engaging (E-ball): concerns engaging with real-world situations. Involves the practitioner’s choices in orientation and approach, affecting how the situation is experienced.

- Context (C-ball): concerns how systems practitioners contextualise specific approaches in real-world situations. Involves understanding the relationship between a systems approach and its application, going beyond merely choosing a method.

- Managing (M-ball): concerns the overall performance of juggling and effecting desired change. Involves co-managing oneself and the situation, adapting over time to changes in the situation, approach, and the practitioner’s own development.

Although I’m hoping that my understanding of the juggler isophor deepens dramatically before I start the assessment for this module, the following is based on where I stand at the moment. It’s not the most intuitive way of thinking about things for me, but until I come up with a better isophor, it will have to do.

🔴 Being (B-ball)

The B-ball feels foundational to me, and it seems as if Ison describes it as such. In a video in the course materials, for example, he stands next to a juggler showing how they have their feet planted on the floor, and have a stance which helps them with their practice of juggling.

Similarly, we take a ‘stance’ when it comes to juggling systems. We have a tradition of practice which informs and shapes the way we interact with others and with our environment. For me, some of this includes a strong ethical stance around everything from uses of technology to the problem I have with eating animals. There are some things I cannot help, or rather I have to be aware of as I interact, namely that I am a privileged white male who was born and raised in a post-colonial western nation.

There are other things at play here relating to personality and upbringing. For example, I am aware that I tend to appear more confident and care less about what others think about me than the general population. I tend to say what I think and ‘wear my heart on my sleeve’. Some, including me, might put that down to poor emotional control. These are all factors to take into account when interacting with systems that contain other humans, who also both live in language and who will naturally respond to situations with a degree of emotion.

Finally, my tradition of practice and ‘default approach’ also comes from a rational and reflective tradition within the Humanities, notably Philosophy, History, and the study of Education. I am more likely to be drawn towards explanations that ‘make sense of the phenomena’ from a more judgemental, rationalistic lens, rather than an intuitive one.

🟢 Engaging (E-ball)

If the B-ball is about a stance, then the E-ball is about a choice of orientation that a STiP practitioner takes towards the world. For example, to continue what I mentioned above, it’s possible to engage with a particular situation with more or less emotion, or to conceptualise something as simple or complex. Doing so is a choice.

A quotation that often comes to mind, and which I say to those around me on occasion is a version of this:

Attempt easy tasks as if they were difficult, and difficult as if they were easy; in the one case that confidence may not fall asleep, in the other that it may not be dismayed.

Baltasar Gracián

In other words, we can choose how to frame a situation. From a systems thinking point of view, this involves thinking carefully what words we use, or in fact what we name, as these can lead to situations (or parts of situations) becoming reified. For example, as Ison has pointed out, even talking about a situation as a ‘problem’ (versus a ‘mess’ or ‘of interest’) can change the way we engage with it.

This has the potential to take me down a rabbit hole, but thankfully I wrote a post recently for the WAO blog on the strategic uses of ambiguity which I can point readers towards. In my own life, I think about issues raised by the E-ball a lot, especially since I went through therapy. The CBT process helped me step back from my everyday life and think about what I’m doing; in fact, looking back it was a proto- and meta-version of what I do when I do what I do.

🟡 Context (C-ball)

The C-ball involves, but goes beyond, choosing a method to apply to a situation. As I’ve said in a couple of other blog posts, if all you have is a hammer, then everything looks like a nail. Having a wider range of (reflexive) tools and approaches makes for more choices and a more nuanced approach.

A phrase that changed my life when I first learned and applied it was “good enough for now; safe enough to try”. This comes from Sociocracy and, in particular, a series of transformative workshops I attended from Outlandish. It fits perfectly with my Pragmatic approach to the world which is built upon provisionality, which in turn helped overcome my tendency towards perfectionism.

By saying that something is “good enough for now; safe enough to try” you are providing momentum within guard rails provided by an ethical framework. I hope that the relation to the C-ball is obvious: there are many ways of approaching a given situation, and the intention is to create advantageous changes in a system which are “systematically desirable, culturally feasible and ethically defensible” (Ison, 2017, p.155)

There is a temptation when finding something that ‘works’ with one client and in one particular situation to try and replicate that success elsewhere. But every context is different and therefore requires the contextualisation of “a diverse array of systems concepts and methods” (ibid.). One rather prosaic example of this is the tolerance or appetite that different people and organisations have to theory. Some geek out on it, some really do want you just to get on with the practical side of things. So I would suggest there is a nuanced communication element to the contextualisation represented by the C-ball.

🔵 Managing (M-ball)

If the B-ball describes the relationship between the practitioner and their tradition of understanding, the E-ball the relationship between the practitioner and the situation, the C-ball the relationship between the practitioner and the methods in their toolbox, then the M-ball describes the relationship between the practitioner and their STiP performance. It wouldn’t be ridiculous to describe it as more of a dance.

As far as I understand it, this ball involves an ‘in-play’ metacognitive approach which allows the practitioner to reflect on what they’re doing while they’re doing it. For example, when I work on projects there is usually a ‘goal’ to work towards. But if we take the long view, projects are often nested and/or lead to new projects. The idea is less to encourage “goal-directed practice” and more to foreground “practices that foster innovation and change through managing for emergence and self-organisation” (ibid. p.189).

I’m reminded of the early differentiation in this module between systematic and systemic thinking, which I outlined in my very first reflections:

- Systemic thinking is an approach that considers the complex interactions within a whole system. It recognises that changing one part of a system can affect other parts and the system as a whole, often in ways that are not immediately apparent. This kind of thinking is holistic and focuses on patterns, relationships, and the dynamics of systems.

- Systematic thinking, on the other hand, is a methodical and structured approach to problem-solving. It involves following a step-by-step process or a set of procedures to arrive at a solution. It’s more linear and analytical, focusing on order, sequences, and detailed analysis.

When we juggle the M-ball the idea is that we keep on juggling. As a STiP practitioner, the goal is to not drop the balls. Emergence happens not because of a logical step-by-step, pre-ordained march towards a future imagined state. Instead, it comes via purposeful action, intervening systems using an approach which (to use a phrase from William James) is “good in the way of belief”.

References

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

Image: DALL-E 3 (try as I might, it wouldn’t get the fingers exactly right!)