On CC0

There’s a lot to unpack in this post by Alan Levine about his attempts to license (or un-license) his photographs with Creative Commons Zero (CC0). The way I think about these things is:

- Standard copyright: “All Rights Reserved” — I do the innovation, you do the consumption.

- Creative Commons licenses: “Some Rights Reserved” — I have created this thing, and you can use it under the following conditions.

- CC0/Public Domain: “No Rights Reserved” — I have created this thing, and you can do whatever you like with it.

I’m not precious about my work. I donated my doctoral thesis to the public domain under a CC0 license (lobbying Durham University to ensure it was stored under the same conditions in their repository). My blog has, for the last five years at least, been CC0 — although I’d forgotten to add that fact to my latest blog theme until writing this post.

For me, the CC0 decision is a no-brainer. I’m working to make the world a better place through whatever talents and skills that I’ve got. While I want my family to live comfortably, I’m not trying to accumulate wealth. That’s not what drives me. So I definitely feel what Alan says that he’s “given up trying to be an attribution cop”.

I care about the commons, but want to shift the Overton window all the way over to a free sharing economy, rather stay fixated on copyright. To me, things like Creative Commons licenses are necessary to water down and mollify the existing extremely-litigious copyright industry. If I’ve got complete control over my work (as I do) then I’ll dedicate it to the public domain.

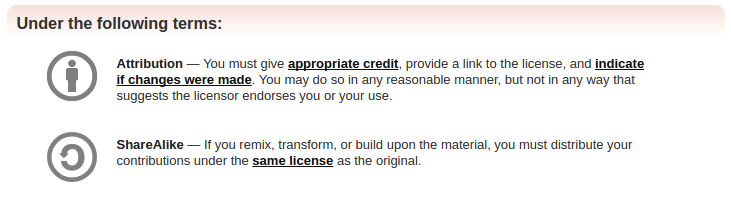

An aside: if you’re theory of change involves obligation, then you’re better off using the CC BY-SA license. Why? It means whoever uses your work not only has to cite you as the original author, but they must release their own work into the commons.

The thing is that despite this all being couched in legal language (which I’m very grateful to Creative Commons for doing) I’m never, in reality, going to have the time or inclination to be able to chase down anyone who doesn’t subsequently release a derivative work under an open license.

In my experience, reducing the barriers to people using your work means that it gets spread far and wide. Not only that, but the further it’s spread, the greater your real-world insurance policy that people won’t claim your work as their own. After all, the more people who have seen your work, the greater likelihood someone will cry ‘foul’ when someone tries to pass it off as their own.

So I’ll continue with my policy of licensing my work under the CC0 license. Not only does it mark out my work as belonging to a community that believes in the commons, but it’s a great conversation starter for people who might be commons-curious…

Image via CC0.press (just because you don’t have to attribute doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t!)