TB872: The people of the PFMS heuristic

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

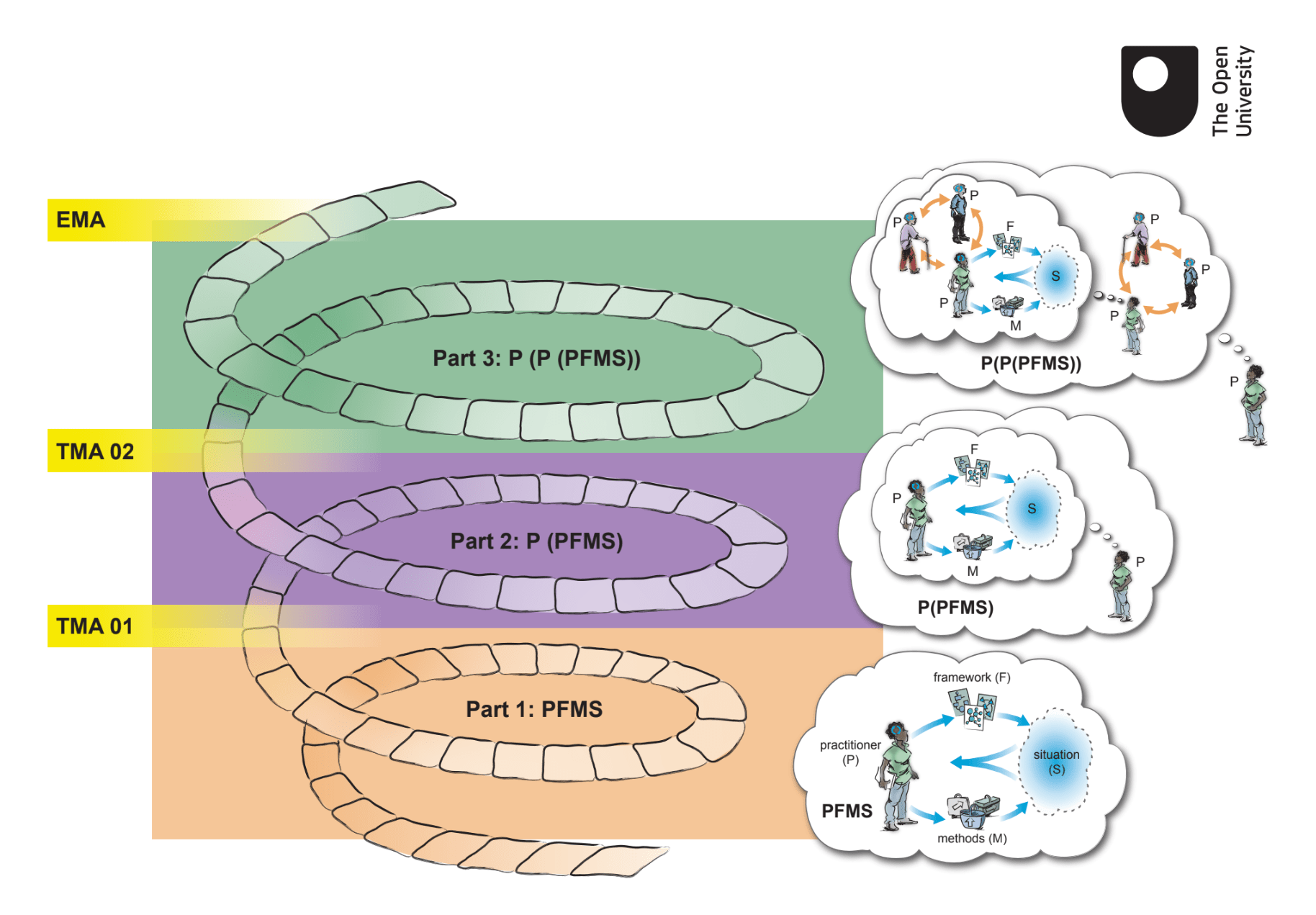

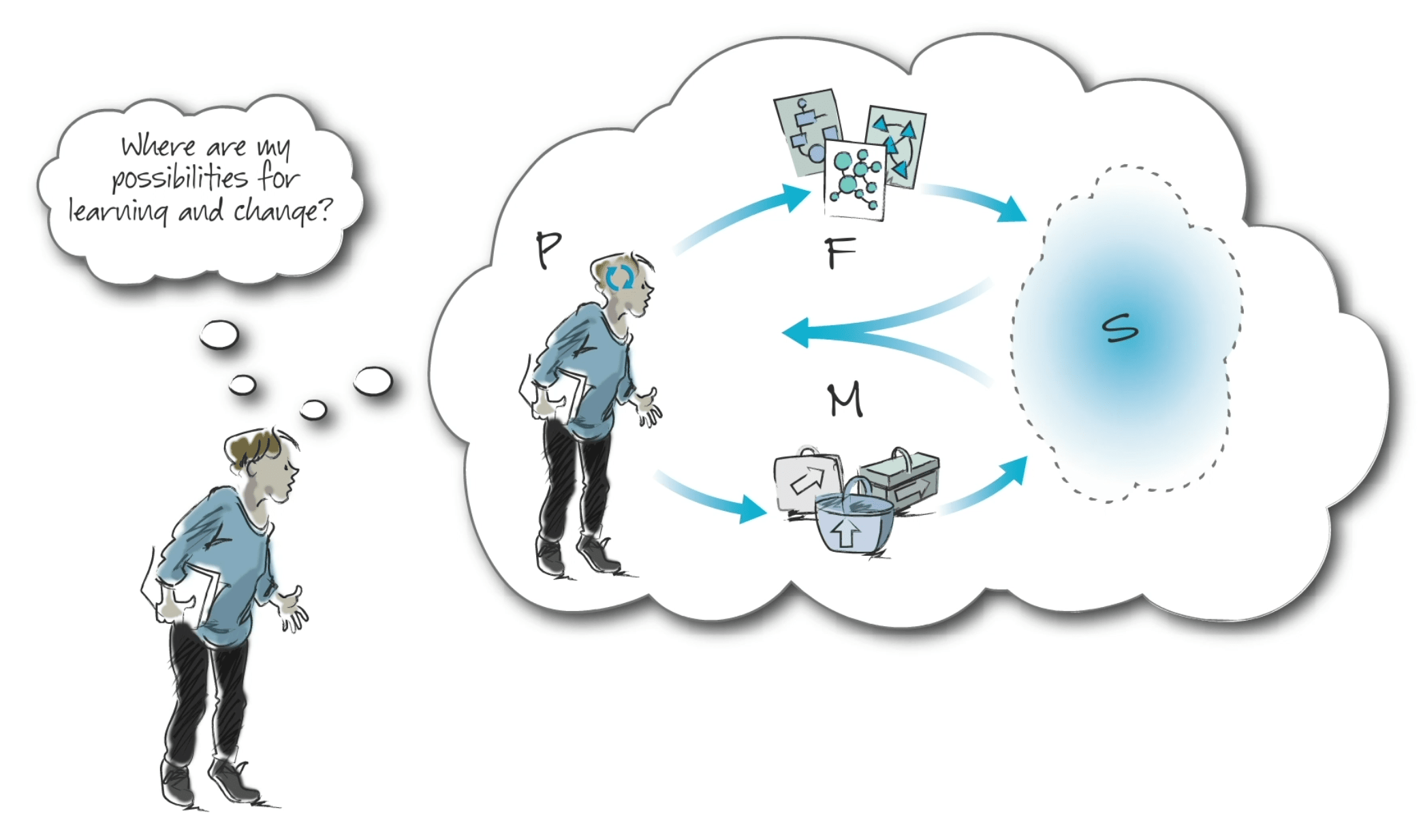

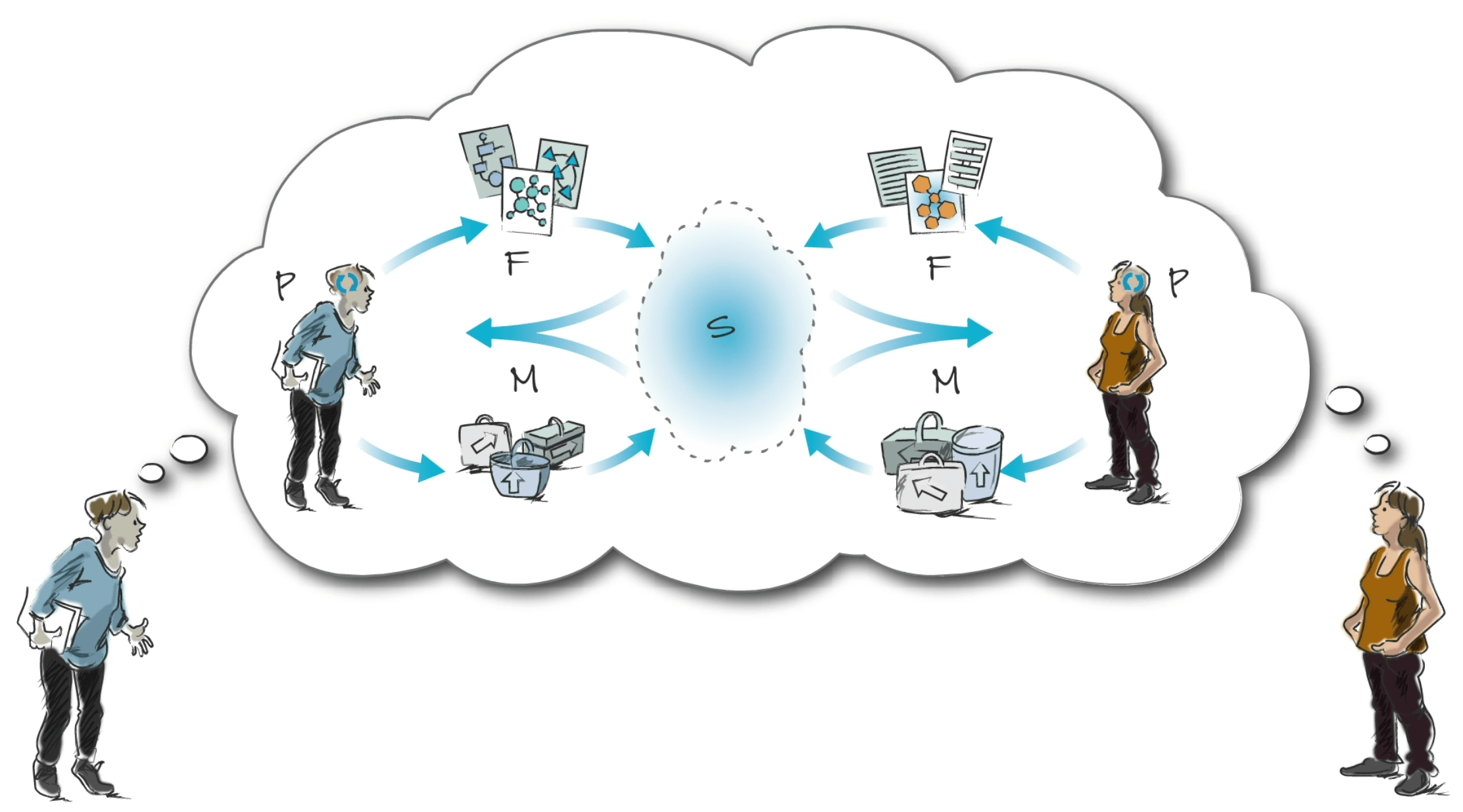

As I’ve explained in a previous post, the PFMS heuristic is at the core of the TB872 module I’m currently studying:

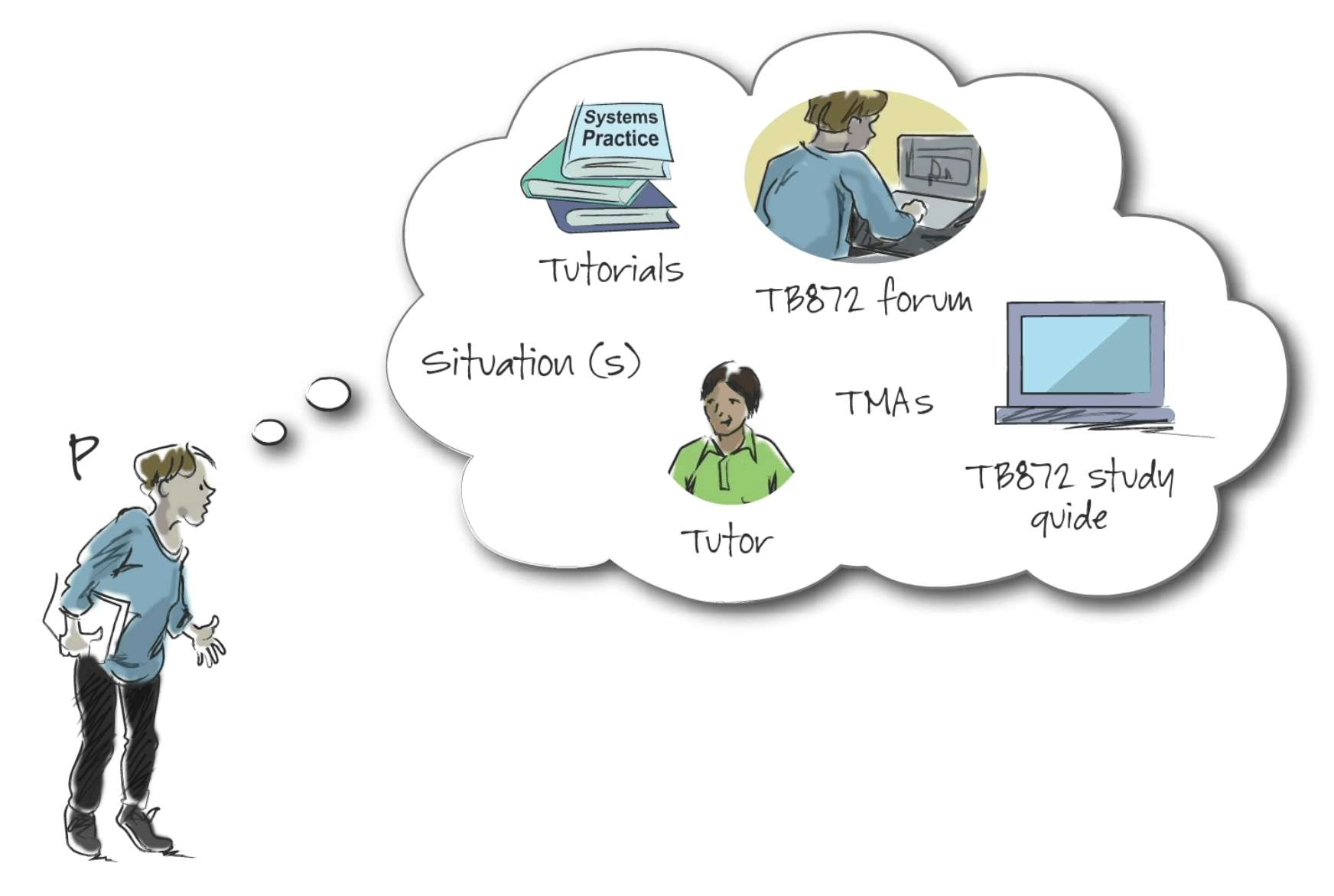

Practitioners (P) Which other practitioners do you work with?

Framework of ideas (F) What ideas are informing your practice? Do you have a shared set of ideas or are you all working with different ideas? Are there particular ideas you have heard about that you would like to explore further?

Methods (M) What methods and tools are you using?

Situations of concern (S) Do you have a shared situation of concern? If so, what is it?

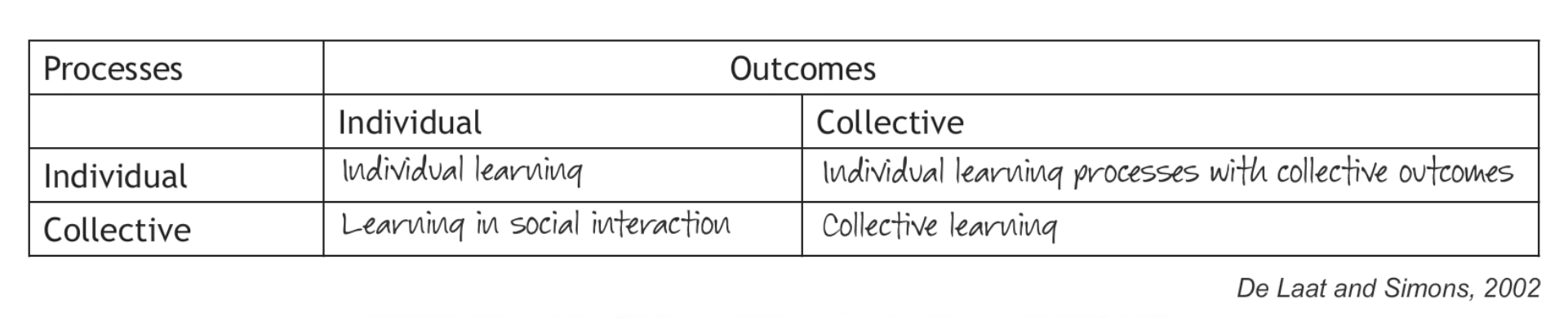

The next activity on my list is to fill in what seems like a straightforward 2×2 table, based on the work of De Laat and Simons (2002). The idea, I think, is to introduce the idea of social learning to those who are perhaps only really conceptualise the kind of individual learning done on traditional university undergraduate courses.

| Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Processes | Individual | Collective |

| Individual | Individual learning | Individual learning processes with collective outcomes |

| Collective | Learning in social interaction | Collective learning |

Taking both the PFMS model and the table together, it’s clear that in my day-to-day work through the co-op of which I’m a founding member, I engage in all four of the kinds of learning:

- Individual learning: all knowledge and belief is contextual and theory-laden, so much of what I learn is based on my own personal experience, observation, and internal reflection. For example, I might learn what to say or not say to a colleague in a given situation. Or I might find out about something from a client who works in a slightly different way to me.

- Individual learning processes with collective outcomes: although learning often occurs at an individual level, the knowledge or skills we acquire can contribute to a larger group’s collective goal. For example, we can pool the expertise we have as a cooperative, and the experience for clients is greater than if they engaged us as individual consultants. In this quadrant, there’s a symbiotic relationship between personal development and collective advancement.

- Learning in social interaction: I’d say about half of my working week is spent ‘co-working’ with members and collaborators of the co-op. As such, learning happens through these interactions by sharing, discussing, and negotiating knowledge. This happens within Communities of Practice (CoP) we’re part of but WAO itself is a CoP, and a place for learning and development as well as for doing business.

- Collective learning: although individual people learn, so do groups, communities and organisations. This goes beyond the simple aggregation of individual learning experience to include the creation of new knowledge through collective effort. To achieve this, there needs to be shared goals, co-creation of knowledge, and mutual engagement. In my working week, this happens most often through networks of co-ops we’re part of (e.g. workers.coop) and CoPs (e.g. ORE).

I’ve been working on the Open Recognition Toolkit this week, and during our working group call we discussed the Plane of Recognition we’re using on this page. Although, like De Laat and Simons’ grid, it involves quadrants, what’s really happening is a continuum. In the former case it’s from traditional, formal recognition to non-traditional, non-formal recognition. In the latter, it’s a continuum of learning that mvoes from the individual to the collective, emphasising the connections between personal knowledge acquisition and social, collaboration knowledge creation.

So, in my Situation (S), the Practitioners (P) I’m working with are primarily Laura, and then on few with John and Anne. In the past there have been other members and collaborators involved, too. The Framework of Ideas (F) that we implement has been negotiated over time, but was helped by us all working together for a few years at the Mozilla Foundation. At our monthly co-op days, we reflect on different aspects of our work together, for example creating pages such as Spirit of WAO which allow us to say together things like:

We believe in:

- Placing ourselves and our work in historical and social contexts so that we can make thoughtful decisions about our behaviours and mindsets.

- Seeing ourselves as part of nature not the rulers of it and acknowledging that there is a climate emergency. We are conscious of the lost lessons and spirit of the indigenous and strive for climate justice.

- Sharing resources to help combat prejudice wherever we see it (including, but not limited to: racism, sexism, ageism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, and hostility relating to education or socio-economic status).

In terms of our methods (M) we try and make these as explicit as possible. So we’re currently using software tools such as Trello, Google Docs, and Whimsical. But we’ve got a Learn with WAO site where we share tools and approaches, which include the templates we use with clients on a range of activities. These are all Creative Commons licensed, as we walk the talk of openness.

In considering the Situations (S) of concern, our work at the co-op often revolves around diverse and sometimes complex projects. Each project brings its own set of challenges and opportunities for learning. Returning to my earlier example of the Open Recognition Toolkit, there were some new things we had to learn about using MediaWiki, even though it’s a tool we’ve used before. Likewise, there was a time when I had to send a somewhat awkward, but necessary, email, to a contributor who was engaging in a way that wasn’t entirely pro-social. As such, the project has required not individual learning but also collective effort to bring together different expertise and perspectives.

A really interesting aspect of thinking through my practice using the PFMS heuristic is how it enables a fluid transition between individual and collective learning processes. For example, I often find that my own, individual, learning about Open Source technologies contributes significantly to the collective knowledge base of the group.

Social learning is essentially learning in practice. It’s not just about exchanging information, but full-bandwidth collaborative experience that inform and shape both our understanding and approaches to work. For example, I’ve seen many instances when people have taken things that they’ve seen us used (and which we learned from others), and then use them in their own practice. Sometimes they even verbalise it: “Oh, I’m going to steal that!”. This encourages a culture of continuous learning and adaptation, which is important in any kind of work environment.

I’m part of the Member Learning group of workers.coop, and in a meeting this week I was trying to explain the value of regular community calls. I was trying to get across the point that the kind of learning we want to foster in the network is not a series of transactional experiences, but rather building a constituency of people who are learning and growing together. It’s not something confined to formal training sessions or workshops. Instead, it’s embedded in our interactions, projects, and shared culture.

As I get further into the TB872 module, I am increasingly appreciative of the way that WAO works internally, with clients, and with other cooperatives. We’ve essentially set up a learning organisation. What’s useful to me is that the PFMS heuristic provides a really valuable lens through which to view and understand these processes, and I’m glad I’m forcing myself to blog all of this so that I can come back to it later!

Image: DALL-E 3 (it reminds me somewhat of a Doom painting you might find on the wall of a medieval church!)