TB872: Places to intervene in a system

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

In Chapter 4 of Systems Practice: How to Act, author Ray Ison includes a reading from Donella Meadows. It stands in quite stark contrast to Ison’s writing as it’s more informal, more emotionally-informed, and doesn’t include a million footnotes.

The situation described involves a “meeting about the new global trade regime, NAFTA and GATT and the World Trade Organization” (Meadows, quoted in Ison, 2017, p.65). Given that she passed away in 2001, I’m assuming that this meeting must have taken place sometime in the late 20th century. Meadows describes an internal dialogue which demonstrates her frustration at the seeming lack of understanding that those involved are inventing “a HUGE NEW SYSTEM” which is “cranking the system in the wrong direction”. As she tells it, Meadows “marched to the flip chart, tossed over a clean page, and wrote: ‘Places to Intervene in a System’, followed by nine items”.

This discussion of intervention in a system, then, was itself an intervention in a meeting which could be thought of as a system to set up a global trade regime by focusing on growth. Through her intervention, Meadows was trying to explain that when all you have is a hammer, then everything looks like a nail. There are other tools available.

One of the concerns that seems to have led Meadows to march to the flip chart were the “PUNY” negative feedback loops and small parameter adjustments being discussed. She points out that there are “no quick or easy formulas for finding leverage points” and that it can take “a few months or years” to “model the system and figure it out”. When new complex systems are being developed in a matter of days, this speed is not sufficient. Hence the intervention.

The reading details ten ways to intervene in a system, taken from an account published in 1997. A later publication (Meadows, 1999) increased this to 12. The original ten, numbered backwards, are:

9. Numbers (subsidies, taxes, standards)

8. Material stocks and flows

7. Regulating negative feedback loops

6. Driving positive feedback loops

5. Information flows

4. The rules of the system (incentives, punishment, constraints)

3. The power of self-organization

2. The goals of the system

1. The mindset or paradigm out of which the goals, rules, feedback structure arise

0. The power to transcend paradigms

The final item in this list is introduced separately once Meadows has gone through the other nine places to intervene. She describes it as a “kicker”, mentioning that the “highest leverage of all is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to realize that NO paradigm is ‘true’, that even the one that sweetly shapes one’s comfortable worldview is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe” (Meadows, quoted in Ison, 2017, p.77).

What’s refreshing about the reading is how much Meadows cares about her work. Rather than sitting superciliously on the sidelines commenting, she rolls up her sleeves and intervenes. I also like her use of ALL CAPS occasionally in the reading. It helps the reader experience a bit of the passion she has for her subject, which can’t help ‘rub off’ and make us want to do something similar.

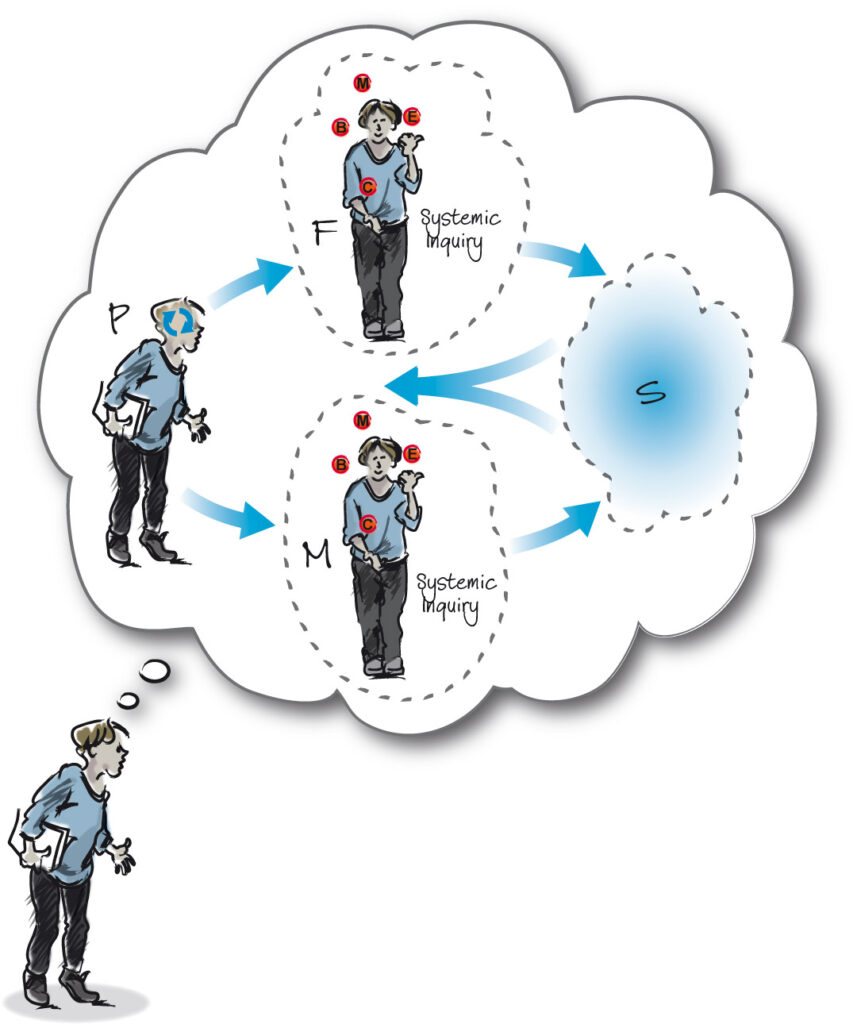

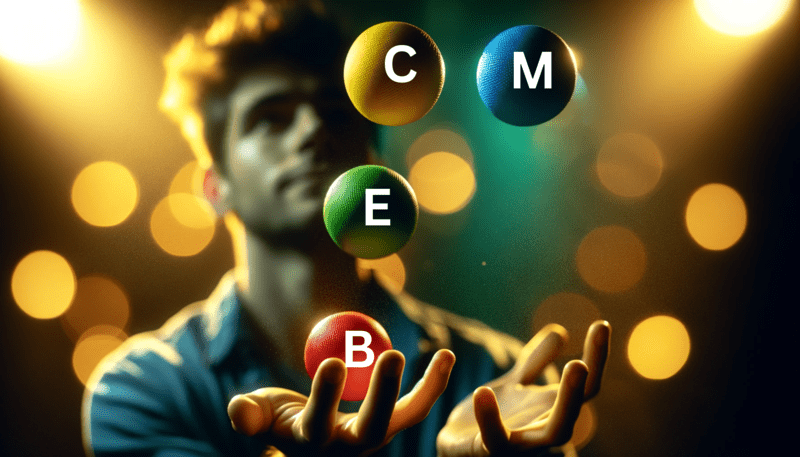

Relating this reading to the isophor of the juggler, it’s clear that Meadows intuitively ‘juggles’ the BECM balls. As a reminder, they are:

- Being (B-ball): concerns the practitioner’s self-awareness and ethics. Involves understanding one’s background, experiences, and prejudices (so awareness of self in relation to the task and context is crucial).

- Engaging (E-ball): concerns engaging with real-world situations. Involves the practitioner’s choices in orientation and approach, affecting how the situation is experienced.

- Context (C-ball): concerns how systems practitioners contextualise specific approaches in real-world situations. Involves understanding the relationship between a systems approach and its application, going beyond merely choosing a method.

- Managing (M-ball): concerns the overall performance of juggling and effecting desired change. Involves co-managing oneself and the situation, adapting over time to changes in the situation, approach, and the practitioner’s own development.

In this example, then, Meadows can be seen as juggling the balls in the following way:

- B-ball: the intervention stems from Meadows’ self-awareness that what is happening in the meeting trangresses her personal ethics. The reader is made aware of this through the internal dialogue she presents as having been engaged with before standing up and intervening. While her role in the proceedings isn’t mentioned, she must have had some form of seniority or be wearing the mantle of the expert to (a) be in the room, and (b) have been allowed to continue her intervention once it started. In addition, Meadows discusses how complex systems are ‘counterintuitive’ and that the people involved in the meeting didn’t seem to understand this. She therefore felt personal urgency that she was well-placed to be able to step up and do something in this situation.

- E-ball: Meadows could have written a paper after the meeting. Perhaps this would have been the approach of most academics or deep thinkers. However, as I mentioned above, she chose to discuss ways to intervene by intervening herself which is a powerful way of disrupting the status quo and presenting alternative viewpoints. The meeting could not continue ‘as normal’ and therefore would be experienced quite differently by participants who are not used to interventions which make them blink in surprise.

- C-ball: the method Meadows used in this situation, to create a list of leverage points, “was distilled from decades of rigorous analysis of many different systems done by many smart people” (Meadows, quoted in Ison 2017, p.66). Although the list may have been new, it did not come from nowhere. Nor did Meadows simply choose a particular template or framework in an attempt to ‘apply’ an approach to the situation. What she discusses are reasonably-generic ways of intervening in a system, but the stimulus was a very specific situation in which she wanted the group to intervene. This was not theoretical speculation, but something which would have consequences.

- M-ball: this list, or rather the list that it became in a subsequent publication, is perhaps the thing for which Meadows is best-known. She does not ‘back off’ her list, but towards the end of the reading points out that it is empowering to know that there is “no certainty in any worldview”, that “no paradigm is right” but that “you can choose one that will help you achieve your purpose” (Meadows, quoted in Ison 2017, p.77). Meadows calls her list “tentative” with its order “slithery”, pointing to the fact that “there are exceptions to every item on it” (Meadows, ibid, p.78). However, using the list subconsciously over the years, while not perhaps “not transform[ing her] into a superwoman” has helped her come to the realisation that “the higher the leverage point, the more the system resists changing it” (Meadows, ibid.). So it seems that, although Meadows doesn’t use this term, she is suggesting that the list is somewhat of a heuristic rather than a manual.

I’ve never been shy to share my opinions, as those who know me well will testify. I can certainly imagine (pre-therapy, at least) marching over to a flip chart and sharing my thoughts, especially if I felt that an important gathering of movers-and-shakers were heading in the wrong direction. However, it’s a high-risk strategy, as it’s akin to pushing all of your chips into the middle of the poker table and going ‘all in’ on a particular intervention.

The fact that I consumed the reading mostly with a wry smile on my face would suggest that I very much approve of Meadows’ approach. I like the way that she used her experience to intervene in a targeted way and using an approach which was appropriate to the situation. That is to say she used a flip chart instead of a shiny slidedeck, she presented options (as ‘leverage points’) instead of a single direction, and she suggested urgency by the manner in which she intervened.

These days, being rather more conscious of my middle-age, white guy privilege, I’m perhaps less likely to intervene in the way that Meadows did. But I still have it within me, when I think that I know enough about a particular domain, or have a certain approach which I think could help the situation. I think it’s the way that you present ideas or concepts sometimes that helps them be considered/adopted. In this situation, although it was a gamble, and although we don’t discover exactly what happened as a result, it would seem that it might have paid off for Meadows.

References

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. Hartland: The Sustainability Institute.

Image: DALL-E 3