This week, Twitter published an article summarising the steps they are taking to avoid being complicit in negatively affecting the result of the upcoming US Presidential election:

Twitter plays a critical role around the globe by empowering democratic conversation, driving civic participation, facilitating meaningful political debate, and enabling people to hold those in power accountable. But we know that this cannot be achieved unless the integrity of this critical dialogue on Twitter is protected from attempts — both foreign and domestic — to undermine it.

Vijaya Gadde and Kayvon Beykpour, Additional steps we’re taking ahead of the 2020 US Election (Twitter)

I’m not impressed by what they have come up with; this announcement, coming merely a month before the election, is too little, too late.

Let’s look at what they’re doing in more detail, and I’ll explain why they’re problematic both individually and when taken together as a whole.

There are five actions we can extract from Twitter’s article:

- Labelling problematic tweets

- Forcing users to use quote retweet

- Removing algorithmic recommendations

- Censoring trending hashtags and tweets

- Increasing the size of Twitter’s moderation team

1. Labelling problematic tweets

We currently may label Tweets that violate our policies against misleading information about civic integrity, COVID-19, and synthetic and manipulated media. Starting next week, when people attempt to Retweet one of these Tweets with a misleading information label, they will see a prompt pointing them to credible information about the topic before they are able to amplify it.

[…]

In addition to these prompts, we will now add additional warnings and restrictions on Tweets with a misleading information label from US political figures (including candidates and campaign accounts), US-based accounts with more than 100,000 followers, or that obtain significant engagement. People must tap through a warning to see these Tweets, and then will only be able to Quote Tweet; likes, Retweets and replies will be turned off, and these Tweets won’t be algorithmically recommended by Twitter. We expect this will further reduce the visibility of misleading information, and will encourage people to reconsider if they want to amplify these Tweets.

Vijaya Gadde and Kayvon Beykpour, Additional steps we’re taking ahead of the 2020 US Election (Twitter)

The assumption behind this intervention is that misinformation is spread by people with a large number of followers, or by a small number of tweets that can a large number of retweets.

However, as previous elections have shown, people are influenced by repetition. If users see something numerous times in their feed, from multiple different people they are following, they assume that there’s at least an element of truth to it.

2. Forcing users to use quote retweet

People who go to Retweet will be brought to the Quote Tweet composer where they’ll be encouraged to comment before sending their Tweet. Though this adds some extra friction for those who simply want to Retweet, we hope it will encourage everyone to not only consider why they are amplifying a Tweet, but also increase the likelihood that people add their own thoughts, reactions and perspectives to the conversation. If people don’t add anything on the Quote Tweet composer, it will still appear as a Retweet. We will begin testing this change on Twitter.com for some people beginning today.

Vijaya Gadde and Kayvon Beykpour, Additional steps we’re taking ahead of the 2020 US Election (Twitter)

I’m surprised Twitter haven’t already tested this approach, as it’s a little close to one of the most important elections in history to be beginning testing now.

However, the assumption behind this approach is that straightforward retweets amplify disinformation more than quote retweets. I’m not sure this is the case, particularly as a quote retweet can be used passive-aggressively, and to warp, distort, and otherwise manipulate information provided by others in good faith.

One of the things that really struck me when moving to Mastodon was that it’s not possible to quote retweet. This is design decision based on observing user behaviour. It’s my opinion that Twitter removing the ability to quote retweet would significantly improve their platform, too.

3. Removing algorithmic recommendations

[W]e will prevent “liked by” and “followed by” recommendations from people you don’t follow from showing up in your timeline and won’t send notifications for these Tweets. These recommendations can be a helpful way for people to see relevant conversations from outside of their network, but we are removing them because we don’t believe the “Like” button provides sufficient, thoughtful consideration prior to amplifying Tweets to people who don’t follow the author of the Tweet, or the relevant topic that the Tweet is about. This will likely slow down how quickly Tweets from accounts and topics you don’t follow can reach you, which we believe is a worthwhile sacrifice to encourage more thoughtful and explicit amplification.

Six years ago, in Curate or Be Curated, I outlined the dangers of social networks like Twitter moving to an algorithmic timeline. What is gained through any increase in shareholder value and attention conservation is lost in user agency.

I’m pleased that Twitter is questioning the value of this form of algorithmic discovery and recommendation during the election season, but remain concerned that this will return after the US election. After all, elections happen around the world all the time, and politics is an everyday area of discussion for humans.

4. Censoring trending hashtags and tweets

[W]e will only surface Trends in the “For You” tab in the United States that include additional context. That means there will be a description Tweet or article that represents or summarizes why that term is trending. We’ve been adding more context to Trends during the last few months, but this change will ensure that only Trends with added context show up in the “For You” tab in the United States, which is where the vast majority of people discover what’s trending. This will help people more quickly gain an informed understanding of the high volume public conversation in the US and also help reduce the potential for misleading information to spread.

Twitter has been extremely careful with their language here by talking about ‘adding’ context for users in the US, rather than taking away the ability for them to see what is actually trending across the country.

If only trends with context will be shown, this means that they are being heavily moderated. That moderation is a form of gatekeeping, with an additional burden upon the moderators of explaining the trending topic in a neutral way.

While I’m not sure that a pure, unfiltered trending feed would be wise, Twitter is walking a very fine line here as, effectively, a news service. Again, as I commented in Curate or Be Curated years ago, there is no such thing as ‘neutrality’ when it comes to news, no ‘view from nowhere’.

Twitter needs to be very careful here not to make things work even worse by effectively providing mini editorials of ongoing news stories.

5. Increasing the size of Twitter’s moderation team

In addition to these changes, as we have throughout the election period, we will have teams around the world working to monitor the integrity of the conversation and take action when needed. We have already increased the size and capacity of our teams focused on the US Election and will have the necessary staffing to respond rapidly to issues that may arise on Twitter on Election night and in the days that follow.

A post on the Twitter blog from last year counted 6.2 million tweets during the EU elections last year. The population of countries making up the EU is only slightly larger than that of the USA, but next month’s election is much more controversial.

In this scenario, Twitter cannot afford (or hire) a moderation large enough to moderate this number of tweets in realtime. As a result, they will have rely on heuristics and the vigilance of users reporting tweets. However, because of the ‘filter bubble’ effect, the chances are that users who would be likely to report problematic tweets may never see them.

In conclusion…

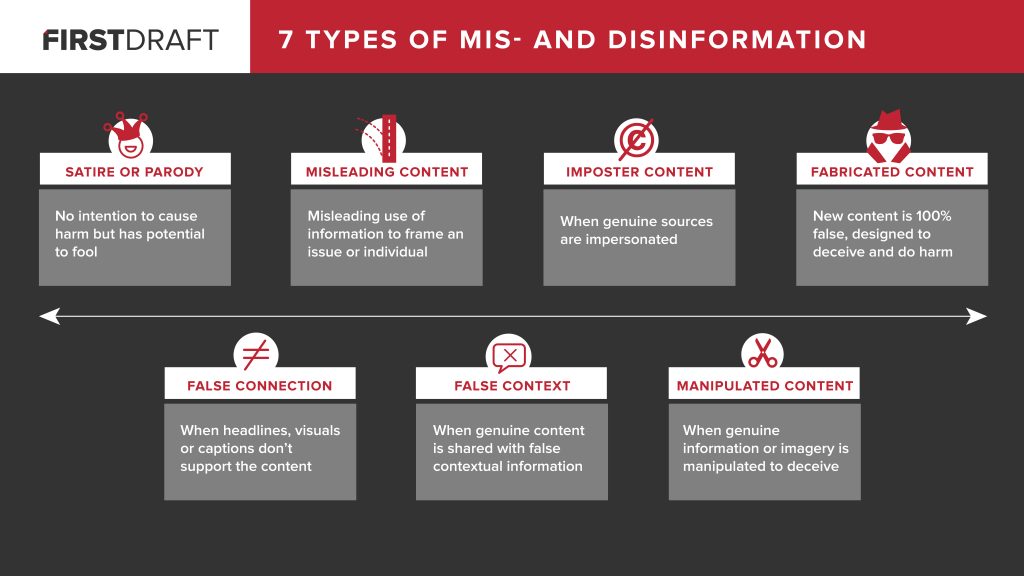

If we step back a little and look at the above with some form of objectivity, we see that Twitter has admitted that its algorithmic timeline is an existential threat to the US election. As a result, it is stepping in to remove most elements of it, and replacing it with a somewhat-authoritarian approach which relies on its moderation team.

From my point of view, this is not good enough. It’s too little, too late, especially when the writing has been on the wall for years — certainly the last four years. I’m deeply concerned about social networks’ role in undermining our democratic processes, and I’d call on Twitter to learn from what works well elsewhere.

For example, on the Fediverse, where I spend more time these days instead of Twitter, developers of platforms and administrators of instances have developed features, policies, and procedures that strike a delicate balance between user agency and disinformation. Much of this comes from a federated architecture, something that I’ve pointed out elsewhere as being much more like how humans interact offline.

This post is already too long to rehash things I’ve discussed at length before, but Twitter has already started looking into how it can become a decentralised social network. In the meantime, I’m concerned that these anti-disinformation measures don’t go far enough.