This is is the first draft of a section for my Ed.D. thesis; please don’t quote it as it’s not the final version.

The bibliography relating to the referenced literature can be found at http://dougbelshaw.com/thesis (I’ve blogged more about my thesis athttp://dougbelshaw.com/blog)

In the last two decades of the twentieth century an interdisciplinary group of academics including Brian Street, James Paul Gee and David Barton started to approach literacy from a sociocultural point of view. They continued to view literacy in a traditional way, as ‘reading and writing’, but looked to move away from defining it as a merely cognitive process. This became known as the ‘New Literacy Studies’ (NLS):

The NLS opposed a traditional psychological approach to literacy. Such an approach viewed literacy as a “cognitive phenomenon” and defined it in terms of mental states and mental processing. The “ability to read” and “the ability to write” were treated as things people did inside their heads. The NLS instead saw literacy as something people did inside society. It argued that literacy was not primarily a mental phenomenon, but rather a sociocultural one. Literacy was a social and cultural achievement-it was about ways of participating in social and cultural groups-not just a mental achievement. Thus, literacy needed to be understood and studied in its full range of contexts-not just cognitive but social, cultural, historical, and institutional, as well. (Gee, 2010:10)

Literacy, therefore, was no longer a journey that a teacher could take a child upon to a predictable destination, but something that resulted from thought and an evolving understanding of the world. Literacy became a construct.

In fact, a plurality of literacies is necessary, NLS theorists argue, because texts can be read in different ways. The Bible, for example, can be read from a religious, historical or hermeneutic point of view meaning that literacy always involves ‘apprenticeship’ to a group. Being literate is always being literate for entry into a particular community or group:

Many different social and cultural practices incorporate literacy, so, too, there many different “literacies” (legal literacy, gamer literacy, country music literacy, academic literacy of many different types). People do not just read and write in general, they read and write specific sorts of “texts” in specific ways; these ways are determined by the values and practices of different social and cultural groups. (Gee, 2010:11)

Proponents of the NLS therefore do not literacy directly but always through the lens of organizations, institutions and groups. The ‘manifesto’ of NLS is a book edited by Cope and Kalpublished in the year 2000 entitled Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. Despite this, Gee, one of the contributors to the book believes that NLS ‘never fully cohered as an area’ (2010:12). Confusingly, NLS bred the new literacies studies which, instead of focusing on viewing literacy in a new way, investigated literacies beyond print literacy. To demarcate the two, Gee refers to new literacies studies as New Media Literacies Studies (NMLS). As suggested by its name, the latter is particular interested the ‘literacies’ associated with media and popular culture:

The emphasis is not just on how people respond to media messages, but also on how they engage proactively in a media world where production, participation, social group formation, and high levels of nonprofessional expertise are prevalent. (Gee, 2010:19)

The NLS is part of a wider ‘social turn’ which shifted the focus away from individual minds towards social interactions. Proponents of NLS argue that literacy (i.e. ‘reading and writing’) is always for a purpose and therefore must be understood as operating within social and cultural contexts. The specific practices of literacies, taking place within specific contexts are known as ‘discourses’. Understanding literacy as operating within such discourses can lead to two different types of ‘new literacy’.

The first type of ‘new literacy’ comes through understanding what is ‘new’ as being the ‘digital’ element of literacy: examples of this include word processing and hypertext. Whilst the context (and therefore the discourse) may have changed, literacy still involves reading and writing text. In terms of the denotative and connotative elements of ‘literacy’ we explored in Chapter 5, this definition is remains towards the denotative end of the spectrum.

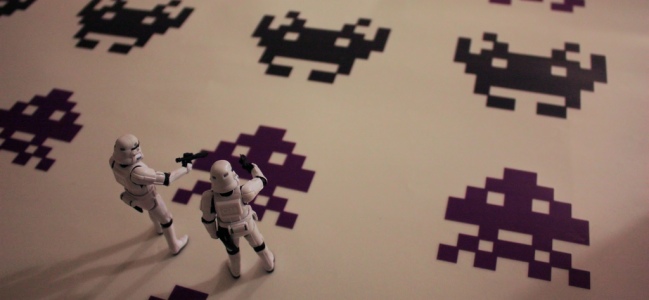

The second type of ‘new literacy’, however, resides closer to the connotative end of the literacy spectrum. Here, ‘literacy’ remains ‘reading and writing’ but these elements are understood in a post-typographical and metaphorical way. In the same way as a footballer might be said to ‘read’ a game, so this second type of ‘new literacy’ employs a definition towards the connotative end of the literacy spectrum that embraces non-written methods of communication. Examples here include the type of ‘mash-ups’ prevalent on video-sharing websites such as YouTube and often include memetic and other meta-level elements.

As Lankshear and Knobel (2006) have pointed out, educational practices within the realm of the first type of new literacy often fall into the trap of ‘old wine in new bottles’. Just because new contexts are being used through the use of new technologies does not mean that any form of ‘literacy’ is involved. For new discourses to be created both new contexts and new literacy practices are necessary. In other words, literacy is more than the mastery of procedural skills.

Literacy, as we have alluded to elsewhere, confers some kind of status to a set of practices. For something to be a ‘literacy’ means that it is a socially-acceptable practice to be engaged in and, therefore, something with which an ‘educated’ person needs to be familiar. As with the Australian ‘literacy wars’ mentioned in Chapter 2, there is a tendency for educational institutions – conservative at the best of times – to focus on the denotative, procedural, and cognitive elements of literacy. The sop given to the ‘social turn’ of NLS is to use traditional literacy practices with new technologies: requiring students to ‘type up’ their essays, for example, or produce a PowerPoint presentation. These, however, neglect to immerse and induct young people into the kind of ‘discourses’ that they encounter outside and beyond school, college and university. There is no ‘cognitive apprenticeship’ (Ghefaili, 2003) but merely a semblance, a veneer, of new literacy practices where old ones persist.

- Gee, J.P. (2010) New Digital Media and Learning as an Emerging Area and “Worked Examples” as One Way Forward (Amazon Kindle edition, page numbers approximated)

- Ghefaili, A. (2003) ‘Cognitive Apprenticeship, Technology, and the Contextualization of Learning Environments’ (Journal of Educational Computing, Design & Online Learning, Vol.4, Fall 2003)

- Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2006) – New Literacies: Everyday Practices and Classroom Learning