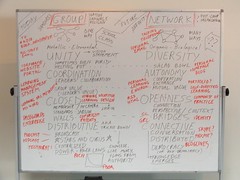

Types of relationship and communities of ‘ought’.

Introduction

The most fertile time of my week, ideas-wise? Sitting listening to sermons in church every Sunday. For whatever reason – perhaps because I can think at least twice as quickly people talk – I end up scrawling ideas for blog posts and reminders of things to look-up on the back of my service sheet. Other members of the congregation no doubt think I’m making notes on the talk.*

Today’s sermon was on The Gospel and Witness, which made me think about relationships within communities. I consider the following a work-in-progress, but share my thoughts in a quest for rejection-or-reinforcement – and perhaps even examples/counter-examples.

Types of relationship

At the lowest level are fleeting relationships, those in which we expend very little energy. We offer politeness but no access to our ‘inner world’. This kind of relationship is transactional and, indeed, is perhaps best illustrated by purchases made in shops.

Next up comes networks. Acquaintances, perhaps friends of friends, people you follow and rarely interact with on Twitter. This sort of relationship is give-and-take. I give some small part of myself and in return get something back of use. An example might be indicating that I’m looking for a new car or music recommendations and in return gain some generic feedback.

Further up the chain are groups. These are defined either implicitly or explicitly and exist for customised advice and support. These too can exist via social networks, but – online at least – are perhaps best facilitated through forums. Examples include getting constructive criticism of a new document you’ve drafted, advice about a particular situation encountered, and so on.

After groups come communities of practice, as defined by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger:

A community of practice (CoP) is… a group of people who share an interest, a craft, and/or a profession. The group can evolve naturally because of the members’ common interest in a particular domain or area, or it can be created specifically with the goal of gaining knowledge related to their field. It is through the process of sharing information and experiences with the group that the members learn from each other, and have an opportunity to develop themselves personally and professionally. CoPs can exist online, such as within discussion boards and newsgroups, or in real life, such as in a lunchroom at work, in a field setting, on a factory floor, or elsewhere in the environment. (Wikipedia)

Whilst informal, communities of practice are focused on a particular end and have pre-determined boundaries. Their focus means that communities of practice are likely to be more successful than groups. Relationships are likely to be predicated upon either informal or formal entry requirements (e.g. job, ownership of an item, previous experience)

The final type of relationships are within a community of ought. This is a term I’ve invented to describe those organizations that have the power to tell individuals (or at least strongly advise them) how to behave. This, of course, includes most religious organizations, but really any organization where an individual defers in some way to authority. Such deference does not have to be formal in nature, but must include adherence to some kind of code or set of rules. Others in the organization must be able to tell whether an individual is ‘doing as he/she ought’.

Conclusion

Although some may feel my description of ‘communities of ought’ sounds somewhat controlling and scary, people do in fact, in some areas of their life (he says, making a huge generalisation), prefer to defer to authority. And, if so, it’s much better to defer to an authority within a community than an individual earthly authority.

This post is more an observation of my own thinking than a statement as to whether such communities of ought should or should not exist. I’m currently thinking that communities of ought are more likely to get things done. I’d be interested in your thoughts, however.

* Before you castigate me for my irreverance, I’m fully able to have a debate about the theological implications of the sermon afterwards as well, thank you very much. :-p