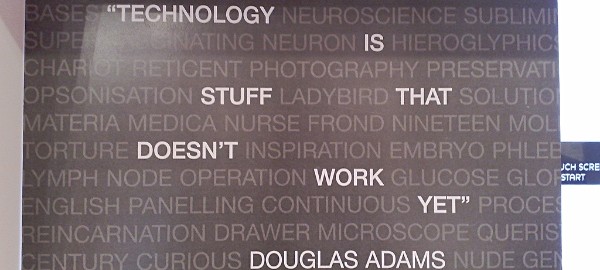

At the London Festival of Education on Saturday I was on a panel about learning technologies in the classroom. You can see my notes in a previous blog post. One of the questions I received (or chose to respond to) was from a self-proclaimed applicant for a ‘bolshy questioner’ badge. Whilst I dismissed his main question as unhelpful, he did make one very good point: I hadn’t defined what I meant by ‘technology’.

It’s human nature to focus on negative feedback – perhaps it’s evolutionary, I don’t know. Whilst it can be destructive if dwelt upon (see this Oatmeal cartoon, for example) it can also spur your own thinking. And that’s what I’ve been doing over the past few days, until I stumbled across the following in Kevin Kelly’s book What Technology Wants.

To make the lengthy quotation slightly shorter, I should explain that techne is a word the ancient Greeks used for art, skill or craft. It’s closest to our word for ‘ingenuity’:

In the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution was one of several revolutions that overturned society. Mecchanical creatures intruded into farms and homes, but still this invasion had no name. Finally, in 1802, Johann Beckmann, an economics professor at Gottingen University in Germany, gave this ascending force its name. Beckmann argued that the rapid spread and increasing importance of the useful arts demanded that we teach them in a “systemic order.” He addressed the techne of architecture, the techne of chemistry, metalwork, masonry, and manufacturing, and for the first time he claimed these spheres of knowledge were interconnected. He synthesised them into a unified curriculum and wrote a textbook titled Guide to Technology (or Technologie in German), resurrecting that forgotten Greek word. He hoped his outline would become the first course in the subject. It did that and more. It also gave a name to what we do. Once named, we could now see it. Having seen it, we wondered how anyone could not have seen it.

Beckmann’s achievement was more than simply christening the unseen. He was among the first to recognise that our creations were not just a collection of random inventions and good ideas. The whole of technology had remained imperceptible to us for so long because we were distracted by its masquerade of rarefied personal genius. Once Beckmann lowered the mask, our art and artefacts could be seen as interdependent components woven into a coherent impersonal unity.

If you want to follow this up I recommend reading Cathy Davidson’s Now You See It for more on how ‘attention blindness’ can lead to bad consequences in technology and education.

I’ve said time and time again since writing my thesis that we run into problems when talking about things that can’t be pointed to in the physical world. If I point to an object for sitting on, for example, and say ‘chair’ you may be able to call it something different but (unless you’re an existentialist) can’t really deny its existence. That’s not the case with concepts such as ‘digital literacies’ or even ‘openness’ and ‘Bring Your Own Device’. We can argue what these things are, and what they mean, precisely because we don’t know where the boundaries are.

So technology is the name we give to a loosely-related, amorphous mass of stuff. The word is what William James would call ‘useful in the way of belief’ in that it provides with a way of talking about – a conceptual shorthand for – the kind of things that we’d otherwise have to explain in wordy blog posts like this one. 😉

Image CC BY-NC-SA Andrea in Amsterdam