TB871: Block 3 People stream references

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

A quick post to share the books, articles, and other material referenced in the Block 3 People stream that I might want to come back and explore at some point in the future (Open University, 2020)

Atewologun, D., Cornish, T. and Tresh, F. (2018) Unconscious bias training: an assessment of the evidence for effectiveness. Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/research-report-113-unconcious-bais-training-an-assessment-of-the-evidence-for-effectiveness-pdf.pdf (Accessed: 24 March 2020).

Bezrukova, K., Spell, C. S., Perry, J. L. and Jehn, K. A. (2016) ‘A meta-analytical integration of over 40 years of research on diversity training evaluation’, Psychological Bulletin, 142(11), p. 1227.

Damasio, A. (1994) Descartes’ error: emotion, reason and the human brain. London: Vintage Books.

De Bono, E. (1970) Lateral thinking: a textbook of creativity.. Reprint. London: Pelican, 1977.

De Bono, E. (1981) Atlas of management thinking. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Diamond, J. (2005) Collapse: how societies choose to fail or survive. London: Allen Lane.

Diamond, J. (2012) The world until yesterday: what can we learn from traditional societies? New York: Viking Penguin.

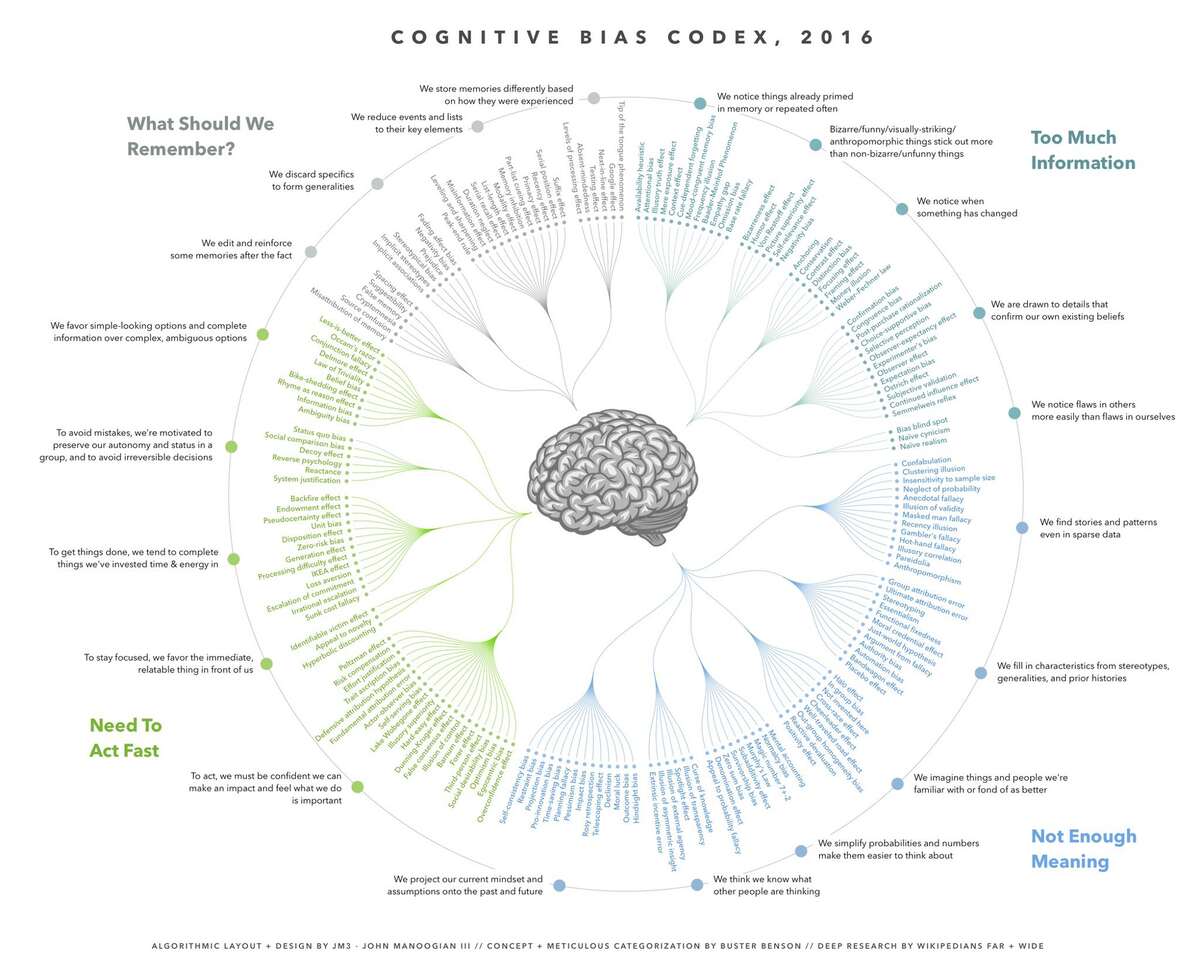

Evans, J. and Frankish, K. (eds.) (2009) In two minds: dual processes and beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Everett, D. (2008) Don’t sleep, there are snakes: life and language in the Amazon jungle. London: Profile Books Ltd.

Girod, S., Fassiotto, M. and Grewal, D. (2016) ‘Reducing implicit gender leadership bias in academic medicine with an educational intervention’, Academic Medicine. 2016(31), pp. 1143-1150.

Goleman, D. (1996) Emotional intelligence: why it can matter more than IQ. London: Bloomsbury.

Henrich, J., Heine, S.J. and Norenzayan, A. (2010) The weirdest people in the world? Working Paper No. 139, RatSWD Working Paper Series. Germany: German Data Forum.

Hoffman, D. (2019) The case against reality: how evolution hid the truth from our eyes. London: Allen Lane.

Hoffman, D. (2019) ‘Do we see reality?’, New Scientist, 3 August, pp. 34-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(19)31434-4.

James, W. (1890) The principles of psychology, (2 vols). New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Janis, I.L. (1982) Groupthink: psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Janis, I.L. (1971) Groupthink. Reprinted from Psychology Today. Available at https://web.archive.org/web/20100401033524/http://apps.olin.wustl.edu/faculty/macdonald/GroupThink.pdf (Accessed: 26 March 2020).

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. London: Penguin Books.

Kelly, G. (1955) The psychology of personal constructs, (2 vols). New York: Norton.

Marks, P. (2009) ‘NASA criticised for sticking to imperial units’, New Scientist, 22 June. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn17350-nasa-criticised-for-sticking-to-imperial-units (Accessed 14 May 2020).

Richardson, J.T.E., (2004) ‘The origins of inkblots’, The Psychologist, 17(6), pp. 334–335.

Richter, I.A., (ed.) (1998) The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci: selections. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simons, D.J., and Chabris, C.F. (1999) ‘Gorillas in our midst: sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events’, Perception, 28(9), pp. 1059–1074.

Syer, J., and Connolly, C. (1987) Sporting body, sporting mind: an athlete’s guide to mental training. London: Simon & Schuster.

Thomas, M.S.C. (2019a) ‘The brain doesn’t like to abstract unless you make it’, in How the brain works. Available at: http://howthebrainworks.science/how_the_brain_works_/the_brain_doesnt_like_to_abstract_unless_you_make_it (Accessed: 26 February 2020).

Thomas, M.S.C. (2019b) ‘Humans apart’, in How the brain works. Available at: http://howthebrainworks.science/humans_apart (Accessed: 26 February 2020).

von Glasersfeld, E. (1995) Radical constructivism: a way of knowing and learning. London: Falmer Press.

Wilson, T., Lisle, D., Schooler, J., Hodges, S., Klaaren, K. and LaFleur, S. (1993) ‘Introspecting about reasons can reduce post-choice satisfaction’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(3), pp. 331–339. doi: 10.1177/0146167293193010.

Winnicott, D.W. (1971) Playing and reality. New York: Tavistock Publications.

References to references

- The Open University (2020) ‘References’, TB871 Block 3 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261488§ion=7 (Accessed 12 July 2024).