TB871: Improvisational intelligence and cognitive niches

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Amoebas are simple organisms that exhibit a kind of ‘improvisational intelligence’ in navigating their environment. Instead of following a rigid path, they adapt their shape and movements on a continual basis in response to changing environmental conditions. This flexibility allows them to navigate terrains, escape predators, and find food.

By ‘improvisational intelligence’ we mean a dynamic adjustment to an entity’s actions in real-time, which addresses immediate challenges/opportunities (rather than relying on predetermined plans). We humans also have a higher-level improvisational intelligence which involves drawing on a ‘bank’ of cognitive and behavioural responses to be able to think and act spontaneously. We’re not acting randomly but using our capacity to respond to unforeseen circumstances in creative and effective ways. This is a critical component of problem solving and innovations, navigating complex real-life situations that can be unpredictable and fluid.

We often find ourselves in similar situations of our own creating. That is to say, living creatures use their cognitive abilities to exploit an environment. For example, a species of bird that uses tools to extract insects from tree bark is in a different cognitive niche than a species that relies on memory to find food that’s hidden. These are cognitive strategies that enhance an organism’s survival and reproduction within its ecological context.

Human cognitive niches are diverse and complex because we live and operate in a wide range of environments and have an increasing range of sophisticated cognitive tools. These expand as we develop not only new technologies, but new social structures and new cultural practices. For example, the development of language has expanded human cognitive niches, and so (arguably) has the use of AI.

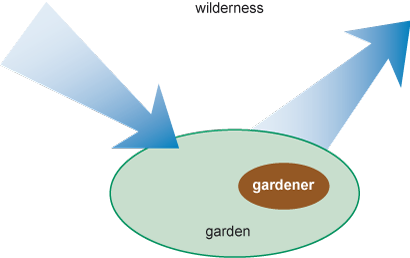

We can make sense of cognitive niches by using the metaphor of a garden. Humans have been creating gardens for at least 3,000 years as a way of shaping and controlling our environment. As such, they serve as a way of visually representing cognitive niches: spaces where we manage and interact with environments we have shaped and/or constructed. Humans create gardens to have an orderly, controlled environment in which to feel safe from the unpredictable and chaotic outside world. They are often carefully designed, and are contrasted with an untamed wilderness.

There is a deep link between improvisational intelligence and cognitive niches. Being able to improvise enhances an organism’s ability to exploit its cognitive niche more effectively. Then, in turn, the demands of a particular cognitive niche can drive the development of improvisational skills. This creates a feedback loop where improvisational intelligence and the characteristics of the cognitive niche continually influence each other.

Improvisational intelligence is something that we could argue distinguishes effective leaders and innovators from their peers. It’s something that allows people to handle unexpected events with ease: everything from personal emergencies to social interactions. This is important when we think about education and personal development, because improvisational intelligence means encouraging critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, rather than learning a fixed body of knowledge.

In addition, because there is a great diversity in cognitive niches, we should tailor educational experiences to individual strengths and environmental contexts to help people feel better prepared for the challenges they are likely to face in their personal and professional lives.

References

- The Open University (2020) ‘P1.1.3 Unknowableness of the world’, TB871 Block 1 Systems and Strategy [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261478§ion=2.3.4 (Accessed 22 May 2024).

Image: Elena Mozhvilo