TB872: Authenticity and accountability

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

I recently finished a book which, although well-written, I didn’t enjoy as much as I expected. A work of non-fiction, I nevertheless felt that the narrator when talking about their own experiences was not being completely honest and straightforward with the reader.

We experience this kind of unease in terms of authenticity all of the time; it’s part of the human condition. While some people live in places and spaces where, for various reasons relating to forms of oppression they can never freely speak their mind, most of us can do so to a greater or lesser extent.

[Authenticity is] the pleasure of participating in togetherness in which one is free to speak for oneself, no in the name of absent others, not under pressure to say things one does not believe in, and not having to hide something for fear of being reprimanded or excluded from further conversation.

(Krippendorff, 2009, quoted in Ison, 2017, p.323)

I should imagine it’s quite different reading the above quotation as a middle-aged white guy compared to anyone who comes from a marginalised group. Treading the line can be exhausting.

But what does this have to do with systems thinking and systems practice?

I’d suggest that, if we consider our practice as a series of conversations with other people, with the literature, and with ourselves, then we should think about the ‘freedom’ we have to speak for ourselves, about things we believe in, without fear of exclusion.

This can be true of the course I’m on and, for example, disagreeing or expressing a different viewpoint to course leaders, tutors, and other students. Although I retain a need to be seen as a “successful” person who tries their best, post-therapy, I’m more willing to take off the ‘mask’ and share some of my concerns, anxieties, and foibles. For example, I asked for an extension for the first time in my academic career for an assessment which would have been due tomorrow. Previously, I would have worked through the night if I’d had to.

[E]verything said is said not only in the expectation of being understood, but also in the expectation of being held accountable for what was said or done.

(Krippendorff, 2009, quoted in Ison, 2017, p.324)

Ultimately, although I have to meet the requirements of the course, I am accountable only to myself. I’m paying for it, and I’m doing it for my own benefit. This explanation is one type of accountability, along with three others that Ison (2017, p.325) outlines: justifications, excuses, and apologies. “Of these only apologies and explanations admit responsibility” he says, while “justifications and apologies admit the speaker’s agency, unlike excuses”.

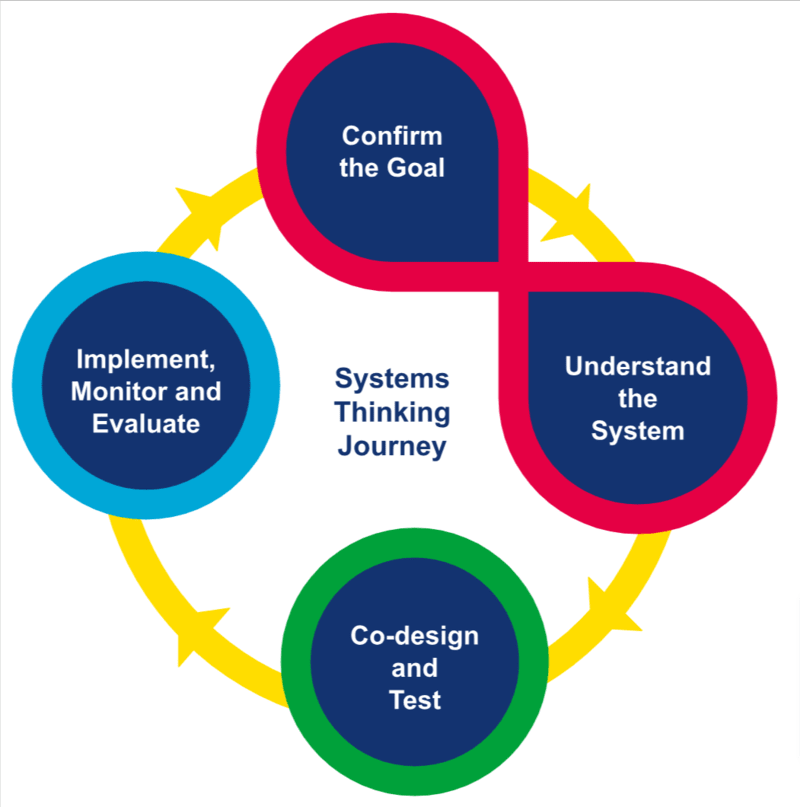

As I’ve said before, this module (TB872) involves simultaneously undertaking two ‘systemic inquiries’. The first, S1, is about my own systems practice as I move through the module, learn more, and reflect upon it. The second, S2, is about a particular situation outside of the context of the module. I have explained this in more detail in this post, and created a rich picture for S1 and a rich picture for S2.

Thinking about what I’m doing with my S1 and S2 through the lens of explanations, justifications, excuses, and apologies is an interesting exercise. I’m definitely not someone who over-apologises, but nor do I try and make excuses for my actions. So I’m going to consider explanations and justifications .

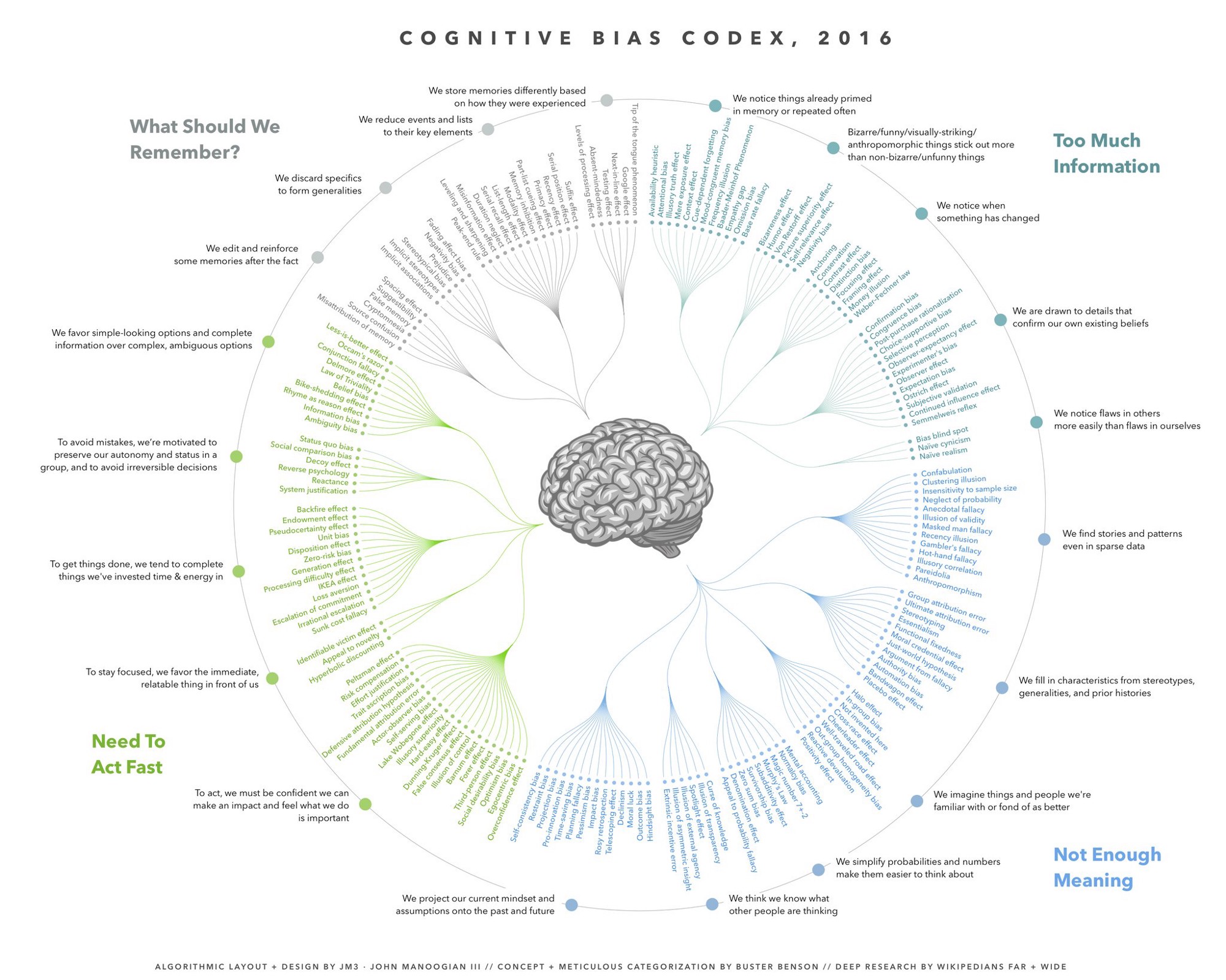

In terms of my S1, returning to the book I mentioned at the top of this post, am I a reliable narrator? Have I been authentic and accountable in my systemic inquiry, or have I attempted to justify any shortcomings (or shortcuts) taken? Have I acknowledged any limitations or biases in my work? In other words, am I subject to the same criticisms as I’ve levelled at the book author?

If I, consciously or unconsciously, misrepresent my systemic inquiry (S1), then who is to know? Other than scores in my assessment tasks, the results are mine alone. Whereas the author might be forgiven for changing the order in which certain things happened in the story, or embellishing them for dramatic effect, how could I explain or justify changes or omissions? Who would I be trying to fool? My tutor? Fellow students? My wife and other members of my family?

No, in terms of my S1 I have been as straightforward as possible with myself and others. I have held myself accountable for any shortcomings in my work, and reflected openly and honestly on any confusion, misunderstanding, or problems I’ve had as I’ve gone along. The only justifications I’ve needed to make have been to myself (to keep going!)

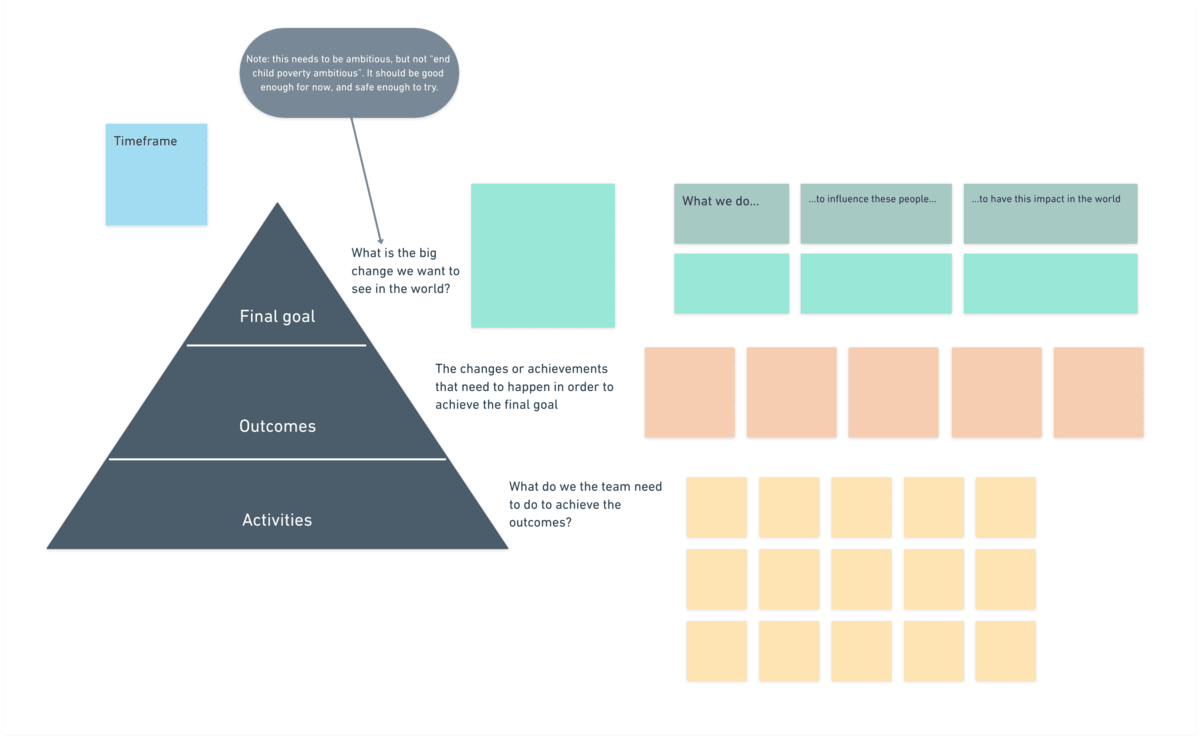

With my S2, on the other hand, other people are involved with whom I have prior relationships. These include fellow members of my co-op, and the client who hired us for this work who I have known for around a decade. Although we were hired to work on documentation, asset creation, and storytelling, as I explained in my previous post, we’ve run user research and Theory of Change sessions to take more of a systemic approach to the work.

Doing this meant explaining to the Director of the DCC what we were attempting to do, and based on our relationship, they trusted us to do the right thing. We had to both explain and justify this, so let’s dig into the differences:

- Explanation — clarify or make something understandable by providing information and context to others. For example, we needed to explain what was involved in the Theory of Change session and provide questions in advance for the user research interviews.

- Justification — defending or upholding an action, decision, or belief as ‘appropriate’ under the circumstances. For example, although it wasn’t difficult to do so, we needed to provide a rationale of the need for user research interviews and Theory of Change session before “getting on with the work”.

Compared to another client we had to which we often compare current ones, this has been very straightforward. With ‘difficult’ clients, they tend to question not only things like day rates but also approaches which involve digging into the reasons and rationale for the way that the organisation does things.

Having the freedom to talk with key stakeholders for the work that comprises my S2 is extremely important. Clients mediating stakeholder interactions can mean that they make excuses for why things don’t match what they’ve previously told you. I much prefer working in an environment where people are open to new experiences and to change.

References

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

Image: DALL-E 3