TB872: Four pervasive institutional settings inimical to the flourishing of systems practice

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

This post builds upon a previous one about ‘projectification’ and ‘apartheid of the emotions’ and deals with Chapter 9 of Ray Ison’s Systems Practice: How to Act in which he outlines four settings that constrain systems practice.

They are:

- A pervasive ‘target mentality’

- Living in a ‘projectified world’

- Failures around ‘situation framing’

- An ‘apartheid of the emotions’

When I wrote the previous post, because of the way this module is structured I had not studied the juggler isophor. Reading this chapter again with a new frame of reference is enlightening:

In my experience systems practice which only focuses on methods, tools and techniques is ultimately limited in effectiveness. This is particularly so at this historical moment because the organizational and political situation has generally not been conducive to enacting systems practice… [T]o be truly effective in one’s systems practice it may mean that changes have to be made in both practice and situations so that practice is re-contextualised.

Ison (2017, p.224)

A couple of days ago, I wrote about exactly this: that, from what I can see, governmental approaches to ‘systems thinking’ are very much about “methods, tools and techniques” in a world of targets and projects. Instead of understanding context and emotions, systems are framed as being ‘out there’ in the world (rather than human constructs).

While discussing the characterisation of natural resource issues as ‘resource dilemmas’, Ison (ibid., p.238-9) outlines a ‘framing shift’ which incorporates five elements:

- Interdependencies

- Complexity

- Uncertainty

- Controversy

- Multiple stakeholders and/or perspectives

What I like about this in relation to my own work is that these are often exactly the kind of things that hierarchical organisations (and most clients) want to minimise or avoid talking about. And I would suggest that it is this reticence that leads to an over-use of targets, rampant projectification, failures around situation framing, and an apartheid of the emotions.

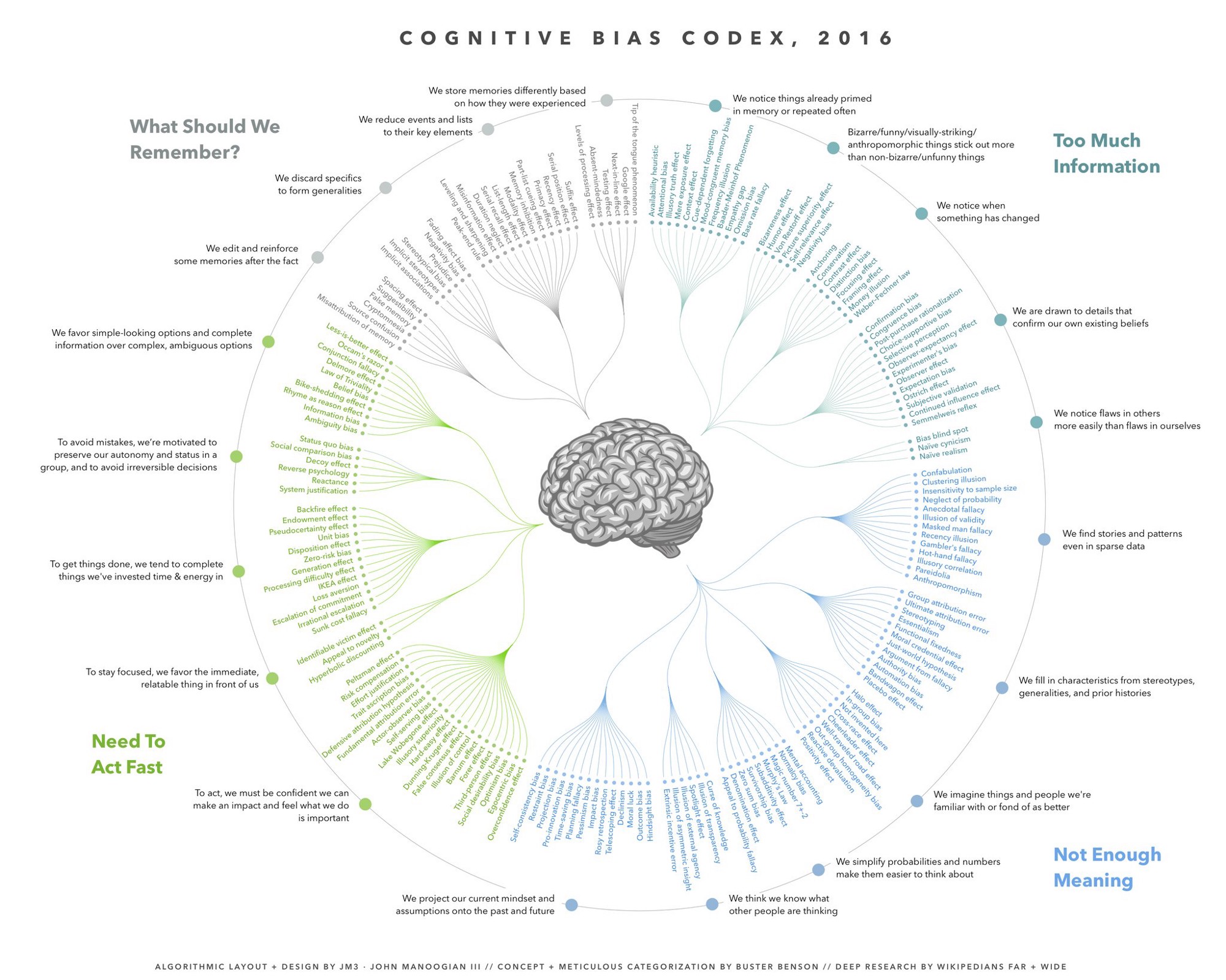

What is possibly missing from all of this is the psychological element of working with others. This is related to, but separate to emotions, and is perhaps most easily understood through the grouping that Buster Benson has made of over 200 cognitive biases to which we as humans are subject:

- “There’s too much information to process, and we have limited attention to give, so we filter lots of things out.”

- “Lack of meaning is confusing, and we have limited capacity to understand how things fit together, so we create stories to make sense of everything.”

- “We never have enough time, resources, or attention at our disposal to get everything that needs doing done, so we jump to conclusions with what we have and move ahead.” (Benson, n.d.)

I’ve had the following image on the wall of my office for the last five years:

Just like the PFMS example, we deal in heuristics because of our human psychology. That means that we tend to simplify things based on prior experience, reducing complexity and uncertainty where possible, doing uncontroversial things so that we don’t have to get input from lots of people (and deal with their needs). It’s entirely understandable. But, as the subtitle and context of Ison’s book suggests, this isn’t going to cut it for dealing with “situations of uncertainty and complexity in a climate-change world”.

In terms of my own experience, I’m not even sure where to start. I began my career in UK schools, that is to say in institutions that are extremely hierarchical, deal in social reproduction, and are filled with staff members who (mostly) did well at school themselves. In addition, change is exogenous in this sector, coming from politically-motivated announcements from ambitious government ministers eager to placate the right-wing tabloid press.

As such, my experience of working in schools was of hard-working and well-meaning staff cosplaying what they thought people do in a business setting. Young people were reduced to numbers on a spreadsheet, and things might have worked very well in the classroom in practice, but they didn’t work well in theory, so they were canned. I loved teaching. I didn’t enjoy everything that was wrapped around it.

If education is a system to inspire the lifelong learning of young people by introducing them to a range of experience, which would be my framing, then the system was failing when I was a teacher, and is failing my own children.

I’m not going to rehearse my career history, but instead I’ll compare and contrast this with my current practice as part of the co-op of which I’m a founding member. In this work, although we have better and worse clients, we get to lean into the ambiguity, the uncertainty, and the complexity that results when humans work with one another.

We endeavour to call the way we work with clients a ‘partnership’ rather than simply working on a ‘project’. I’ve been inspired by people like Kayleigh Walsh, who we interviewed in Season 4 of our podcast, and how they bring their full selves to work. Even with straight-faced, straight-laced people who work for ‘serious’ organisations it’s possible to treat one another as human beings subject to good days, bad days, and all of the emotions that go with the various seasons of our lives.

Some of this has been brought home to me in the last week or so, with the contrast between two organisations. One, partly because of funding constraints, asked us to go through an involved, time-consuming process in order to respond to an Invitation to Tender (ITT). Despite the situation we were potentially going into being essentially unknowable without doing the research, we were being asked for project plans and all kinds of details at which we could only guess.

It reminded me very much of what Ison describes in Chapter 10 of Systems Practice, except we weren’t particularly in a position to suggest another approach; we just wouldn’t have got the work. To be fair to the people involved in the organisation, I think they knew that a different approach was needed, but they were constrained by the logic of the systematic approach imposed upon them. In other words, systematic thinking prevented a systemic approach.

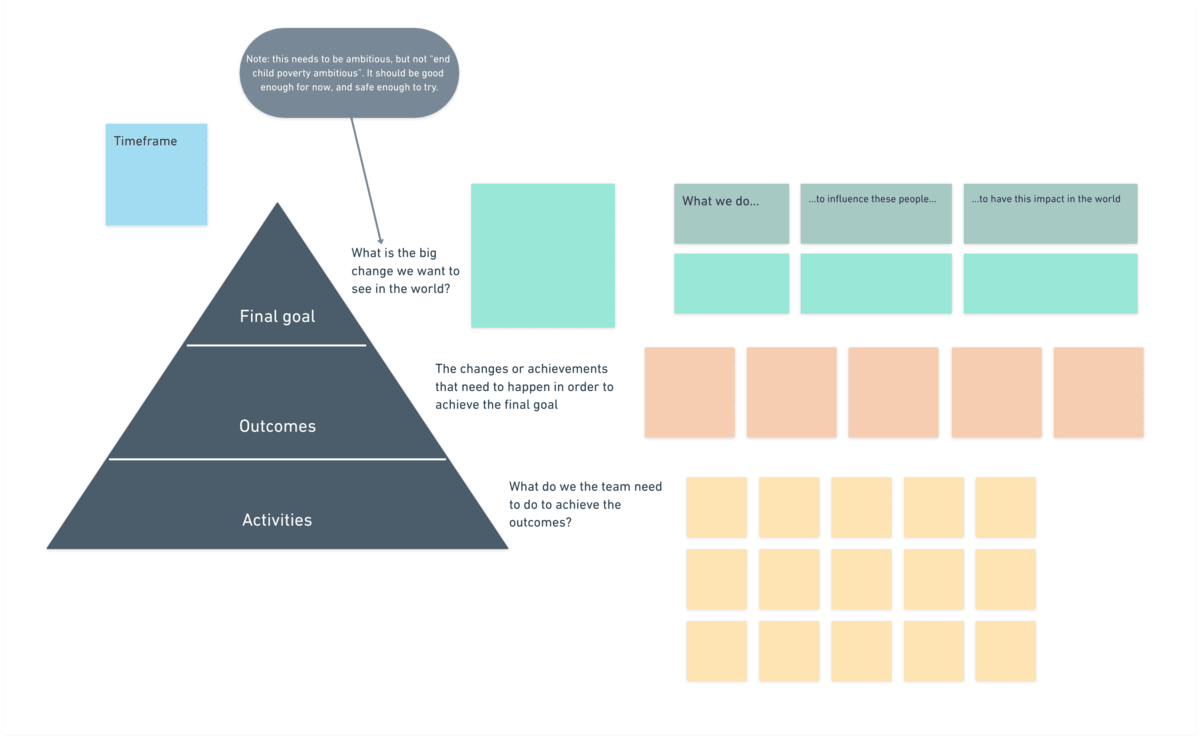

If we compare this with a Theory of Change workshop we ran yesterday for a different organisation, then the difference in approach is clear. An example of the basic template we use for this, based on work by Outlandish, is below:

During the session, we surfaced differences between what came out of the user research with staff members compared with what is included in the reports they publish. We used this as an entry point for each member of the small team to fill in boxes underneath the prompts:

- What we do…

- …to influence these people…

- …to have this impact in the world

As expected, this is not an easy thing to do, and each team member surfaced something slightly different. We then went round the circle twice, first asking everyone to give some context to the text they entered in their three boxes, and then asking for things that someone else mentioned that with which they would definitely agree (or disagree). From there, we attempted through structured conversation a synthesis to create an overall goal.

Sometimes, you just need someone to do some work which fits in as a piece of an extremely well-designed jigsaw. But the number of situations in which this is true is much smaller than most people imagine. In my experience, siloed working and cognitive biases mean that few of us can answer more than a couple of ‘why’ levels deep even in relation to work that is important to us.

As I’ve said before, what I really appreciate about this module, hard and time-consuming though I’m finding it at times, is that it’s a justification of an approach to life that I’ve carried with me from the start of my career. It’s refreshing to realise that I’m not alone in thinking that putting on a suit and tie and talking about KPIs and OKRs is not the right way to improve the world.

References

- Benson, B. (no date). Cognitive biases. Available at: https://busterbenson.com/piles/cognitive-biases/ (Accessed: 31 January 2024).

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems practice: how to act. London: Springer. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

Image: DALL-E 3