I’ve already written a couple of blog posts to reflect on my learning during the first two weeks of a Futurelearn course I’m taking on the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR):

It’s a surprisingly interesting subject, so much so that I’m in danger of, for the first time ever, actually completing an online course that I’m taking voluntarily!

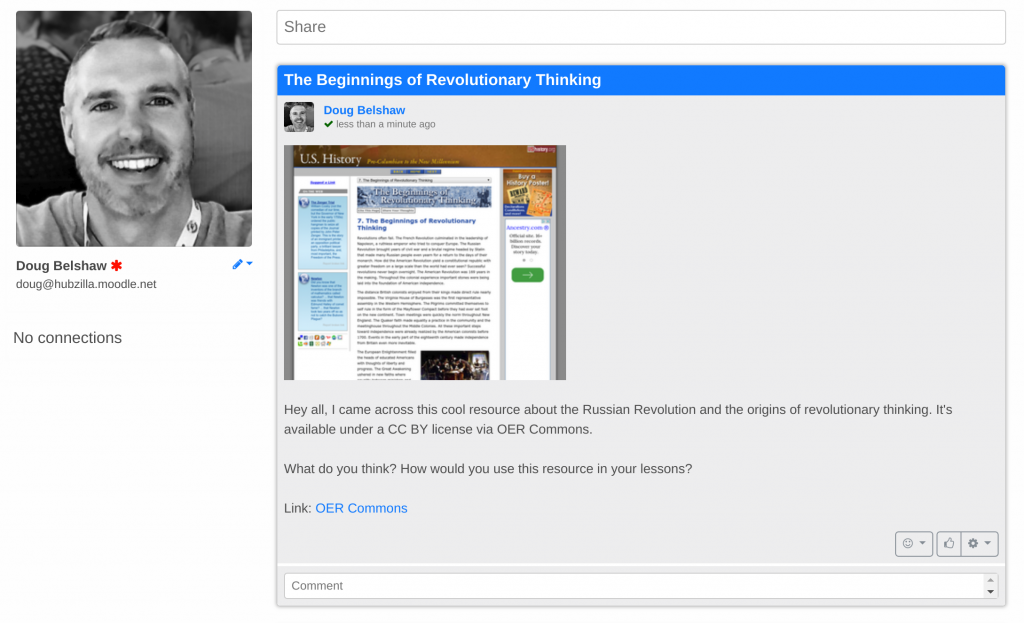

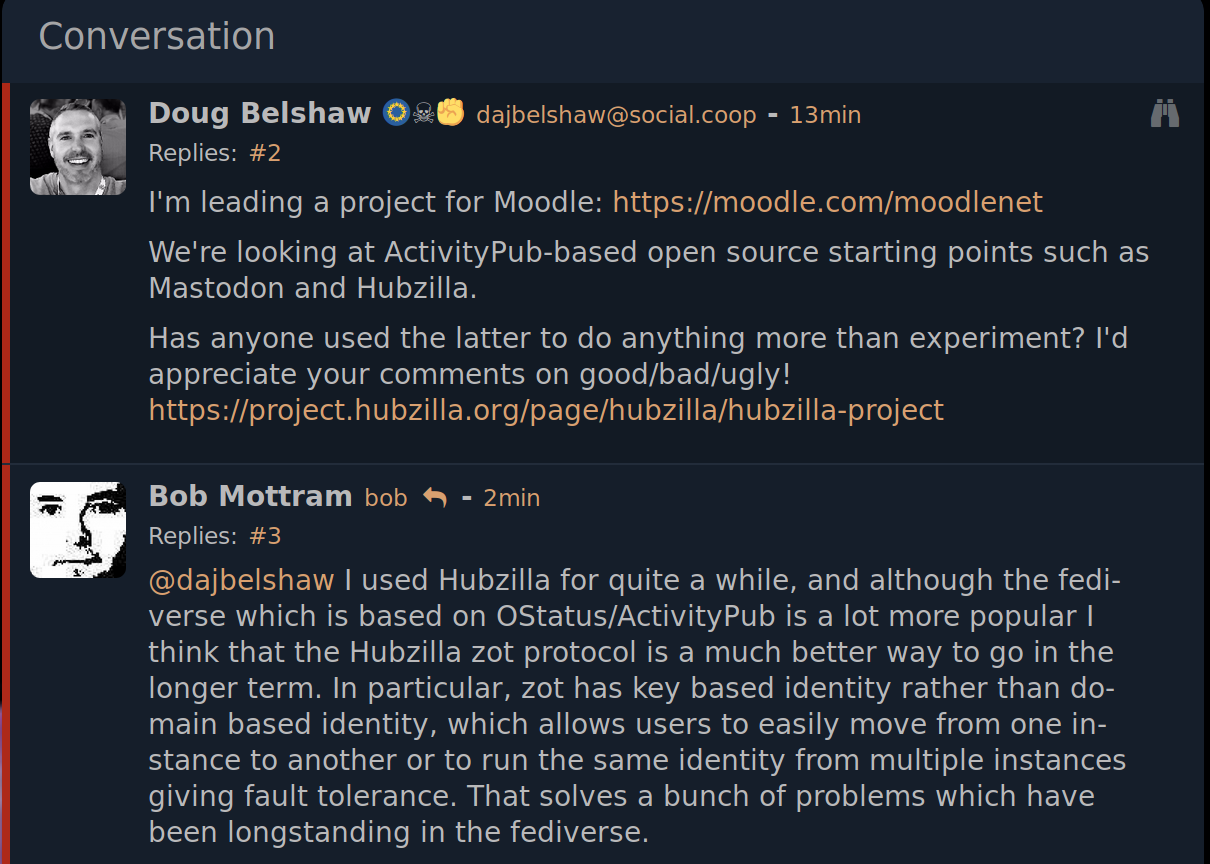

Although it’s my choice, I’m pursuing knowledge in this area because I’m leading Project MoodleNet. However, I’m writing here instead of on the project blog as I’m still coming to grips with all that GDPR means in practice.

Week 3 of the course is all about data controllers and data processors. The quotations I use throughout this post are taken from the course, which I highly recommend (you can sign up for free!)

In brief, data controllers are those who determine the purposes and means of processing personal data. When two or more controllers do so jointly, they are joint controllers. Processors, on the other hand, are those engaged in processing personal data on behalf of controllers. They will follow instructions given by controllers and cannot make decisions on the choice of purposes and means in data processing.

Here’s a more homely metaphor:

To make this more clear: if you visualise a ship and imagine that it is processing data, the controller is the captain and the processors are the sailors. A controller manages and controls the processing of the data (the ship), he determines the purpose (the destination), and the means (or the course of the voyage). A processor is contracted by the controller to carry out data processing for the purpose and with the means determined by the controller. Processors (sailors) act under captain’s instruction and report issues to the controller.

So from a Project MoodleNet perspective, Moodle (the company) is the ship, providing both the purpose and the means. The processor is the Project MoodleNet team which is processing the data. To the end user, the data controller and data processor are effectively one and the same.

Data Controllers

The interesting thing about the GDPR is that you can’t just respect users’ privacy and security, you have to prove that you’re doing so:

First of all, to demonstrate legal compliance is in itself a GDPR obligation. Being able to demonstrate that your organisation is taking compliance measures, both technical and organisational, may save you from potential hazards, such as heavy fines or sanctions. Controllers have to implement appropriate technical as well as organisational measures to make sure that processing of data complies with the GDPR. They have to implement these measures to ensure data protection by design and by default.

One method of doing so is ‘privacy by design’, something covered in a previous week, and which allows you to demonstrate that user-respectiving privacy safeguards are built into your products and services.

However, things can and do go wrong. GDPR therefore mandates what must happen in the event of a data breach:

In the event of a data breach, controllers have the obligation to notify the supervisory authority of that breach.

The supervisory authority in the UK is, I believe, the Information Commissioner’s Office. Moodle is an Australian company that is setting up an office in Barcelona. Until that’s set up, Moodle is processing EU members’ data without a legal presence in the EU. I wasn’t sure what that meant in terms of supervisory authority, so looked it up. Basically, it means that instead of a ‘one-stop shop’ approach, in the event of a data breach, Moodle would have to inform each member state individually.

The data controller has a responsibility to help users exercise their GDPR rights:

Finally, a very important obligation for a data controller is the duty to assist data subjects with exercising their rights to privacy and data protection under the GDPR. For example, a controller has the duty to provide data subject with sufficient information when collecting personal data.

Handily, the Futurelearn course (which is put together by the Universiy of Groningen) has a list of the obligations for data controllers:

Controllers’ obligations may include:

• To maintain records of all processing activities (Article 30 GDPR);

• To cooperate and consult with supervisory authorities (Article 31 GDPR);

• To ensure a level of security (Article 32 GDPR);

• To notify the supervisory authorities in the event of a data breach (Article 33 GDPR);

• To conduct a data protection impact assessment (Article 35 GDPR);

• To appoint a data protection officer (Article 37 GDPR);

• Specific obligations as regards transfer of data outside the EU (Chapter V GDPR);

• To assist data subjects with exercising their rights to privacy and data protection (Chapter III GDPR).

In other words, there’s a lot of companies that are going to have to get a whole lot more transparent about user data very quickly. I feel that we’re in a pretty good position with Project MoodleNet, as we can design all this in from the outset.

Data protection by default

Just as the GDPR advocates privacy by design, it also specifies ‘data protection by default’:

Data protection by default means that, by default, technical and organisational measures need to be taken to ensure that only personal data which are necessary for a specific purpose are processed. This obligation covers the amount of data collected, extent of processing, storage period and accessibility. This means that, by default, the less personal data that are processed, the better. This obligation includes that, by default, personal data are not accessible without the data subject’s intervention.

So, for example, I use an app called FullContact to manage my contacts across various accounts and to automatically update their details. It’s great, and I’m a paying subscriber to their service. When I install it on my Android smartphone, I get a screen which prompts me to give the app access to my contacts:

Given the job I’ve asked the app to do, giving it access to my contacts seems reasonable. I’ve seen other apps, however, request access to my microphone, location, and other ways of gaining potentially sensitive information about me, without any obvious reason why they would need to do so. GDPR compliance prevents this.

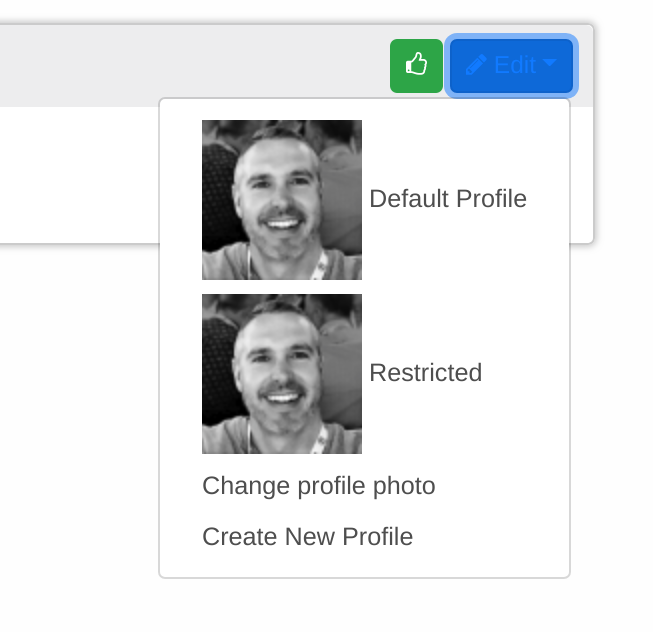

One thing we’ve been discussing with Project MoodleNet is pseudonymisation. Sometimes on a social network, for a whole variety of reasons, you may want to avoid posting with your ‘regular’ account. In this case, token-based pseudonymisation can help:

An example of an effective measure as mentioned in Article 25 is pseudonymisation. Pseudonymisation substitutes the identity of the data subject in such a way that additional information is required to re-identify a data subject. Such measures may also include anonymisation, which irreversibly destroys any way of identifying the data subject.

So, for example, you might be able to generate a finite number of pseudonymous accounts with your login details every month. This would mask your identity when it matters but, if you decided to do something illegal, or troll other members of the network, it would be possible to figure out who you are.

All of this is fascinating as, instead of organisations making it all up as they go along, they have to figure a lot of things out in advance. in order to satisfy their legal requirements and inform the user

When collecting personal data directly from data subjects, the controller has to provide the following information to data subjects at the moment of the obtaining the data:

- The controller’s identity and contact details;

- The contact details of the data protection officer (if applicable);

- The purposes and legal basis for data processing;

- The recipients of the personal data;

- The fact that the controller intends to transfer personal data outside the EU (if applicable).

Furthermore, to ensure fair and transparent processing, the controller needs to provide the following information:

- The reason why the data subject needs to provide personal data (this could be a statutory or contractual requirement or a requirement to enter into a contract), if the data subject is obliged to do so and what the consequences are for not not providing the data;

- Data storage period;

- The rights of data subjects (right to access, rectification, erasure, restriction of processing, objection to processing, data portability, the right to withdraw consent; the right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority);

- The existence of automated decision making (including profiling);

- Any other purposes (if the controller intends to further process the personal data for a purpose other than that for which the data was originally collected).

Over and above this, organisations have to be lot more secure in their data storage and processing procedures.

Under Article 32, controllers have the obligation to take technical and organisational measures to achieve a level of security appropriate to potential risk. When taking these measures, they need to consider the state of the art, the costs of implementation and the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing as well as the risk of varying likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons. Examples of such measures include:

- Pseudonymisation and encryption;

- Ensuring the ongoing confidentiality, integrity, availability and resilience of processing system and services;

- The ability to restore the availability and access to personal data in a timely manner in case of physical or technical incident;

- A process for regularly testing, assessing and evaluating the effectiveness of technical and organisational measures to ensure the security of the processing.

Data breaches

Returning to what happens when and if things go wrong, and user data is compromised, the GDPR makes very specific provisions:

When a data breach occurs, a controller has the obligation under Article 33 to notify the competent supervisory authority within 72 hours after becoming aware of the data breach, unless the breach is unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons. If the supervisory authority is not notified within 72 hours, the controller needs to provide reasons for the delay.

Note the ‘unless the breach is unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons’. In other words, if there’s a data breach but the data is encrypted (as in the case of the LastPass hack) then, as far as I’m aware, while the organisation may choose to notify the supervisory authority, they are not required to do so. Obviously, if personally identifiable information was accessed, then the organisation would need to notify the relevant supervisory authority within 72 hours.

If there’s an elevated risk, then the notification should be immediate. The ‘data subject’ (i.e. user) also needs to be informed, in ways that they can understand:

Furthermore, the controller has the obligation to communicate without undue delay the personal data breach to the data subject under Article 34 if the breach is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons. The communication to the data subject needs to be described in clear, plain and understandable language.

Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)

Interestingly, the GDPR makes provision for new kinds of technologies that may put ‘data subjects’ (i.e. users) at risk. Organisations using new technologies to obtain personally identifiable information are required to carry out a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA):

If there is a chance that a new type of processing (especially when using new technologies) may cause a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons, the data controller needs to carry out a DPIA.

The example in the course is something like using ultrasound to ‘fingerprint’ people. This won’t be a concern for Project MoodleNet, as we’re using pre-existing technologies.

Data Protection Officer (DPO)

Apparently, in earlier drafts of the GDPR, the appointment of a Data Protection Officer (DPO) was mandatory for all organisations that had over 250 employees. However, as I’m sure someone pointed out, when Instagram was purchased by Facebook, it had 27 million users on iOS alone… and only 13 employees.

The final version of GDPR makes no mention of the number of employees an organisation must have before having a DPO is mandatory. Instead, it focuses on the type and scope of the data being processed.

Appointing a DPO is mandatory under certain conditions. Based on Article 37 a controller and processor need to designate a DPO if:

- The processing is carried out by a public authority or body (with the exception of courts acting in their judicial capacity);

- The core activities consist of processing operations that require regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale;

- The core activities consist of processing on a large scale of special categories of data (Article 9) or personal data relating to criminal convictions and offences (Article 10).

Data Processors

As we have already seen, data controllers and data processors are different. Data controllers, using the nautical metaphor introduced earlier, are like the ship’s captain, whereas the data processors are like the crew.

Processors process data on behalf of controllers and under controller’s instructions. Processing has to be governed by a contract or other legal act under EU or national law that is binding on the processor. This contract or legal act, among other things, determines certain obligations for processors and how they assist data controllers in fulfilling their GDPR obligations. Some of these obligations are similar to the obligations of data controllers.

Not only are some of the obligations the same, but as with the case of Moodle and Project MoodleNet, the data controller and data processor are one and the same.

Again, data processors have to be able to demonstrate that they are acting within the terms of GDPR:

The most important obligation for both controllers and processors is to demonstrate legal compliance. Concrete technical and organisational measures (such as documentation, records, Data Protection by Design and by Default, etc.) may provide good evidence to demonstrate compliance with the GDPR.

Applying my learning to Project MoodleNet

Finally, the third week of this course asks a few questions:

- How will you demonstrate compliance? Do you keep records? Do you have a privacy policy? Does your personnel have clear privacy instructions? Do you have clear agreements between controllers and processors?

- Do you need to carry out a DPIA?

- Do you need to appoint a DPO or a representative?

The second and third questions are the easiest to answer. As Project MoodleNet does not involve new technologies that access personally identifiable information, we won’t need to carry out a DPIA. In terms of the DPO, Moodle is currently interviewing for a DPO to be based in the new Barcelona office.

Returning to the first question, Moodle has blogged about how the organisation’s approach to GDPR in terms of its open source learning platform. With Project MoodleNet, however, the answer to the sub-questions around record-keeping, privacy policies, etc. is “we will have”. As I mentioned earlier, one of the benefits of developing this project as GDPR comes into force is that we can build it from the ground with these in place!

Image by jesse orrico available under a CC0 license