I wrote the following (c.2,400 words) today towards my Ed.D. thesis Literature Review, needing to get something written as I’ve neglected my studies for too long. It represents my current thinking, but needs fleshing out (a lot!) and tidying up. I’d very much welcome your comments if you’ve got time to read it critically… 🙂

The concept of ‘literacy’ is akin to the Wittgenstinian problem surrounding the concept of a ‘game’: everyone knows what you mean when you employ the term, but pinning it down in a more formal sense is extremely difficult (Hannon, 2000:36). Simply conceiving of literacy as ‘the ability to read and write’ not only sets up a false dichotomy, but makes no allowance for reading and writing using various tools and for different purposes. Even the Oxford English Dictionary equivocates between two definitions: ‘one who can read and write’ and ‘a liberally educated or learned person’.

Some, such as Holme (2004:7) use the analogy of wave/particle duality in physics to explain how ‘literacy’ can have more than one nature yet still be a single concept. He believes there to be two central questions to the literacy debate, namely: (1) How much does one have to know about reading and writing to be literate? and (2) What does it really mean to read and to write? As Holme comments, these are seemingly simple questions yet are very difficult to answer.

Although not stated explicitly, Holme has a view of literacy that is predicated upon literacy’s relationship with knowledge, as alluded to in his first central question. This is manifest in his brief treatment of concepts of ‘new literacies’ such as ‘computer literacy’:

For example, a core feature of literacy’s meaning is ‘a knowledge’, often of the basic skills, of ‘reading and writing’. Now we use the term to refer simply to basic knowledge as in ‘computer literacy’. Though even more confusingly, computer literacy is also bound up with reading and writing skills. (Holme, 2004:1-2)

This link between literacy and knowledge is taken up by Gunther Kress in Literacy in the New Media Age (2003) in which he asserts, “Literacy remains the term which refers to (the knowledge of) the use of the resource in writing.” (Kress, 2003:24). Kress believes that the communication of ideas and meaning-making are covered by the terms ‘writing’ and ‘speech’. Knowing how to read and write, and then actually going about doing so to communicate meaning is something above and beyond mere ‘literacy’ for Kress.

Despite Kress’ erudition and attempted defence of equating literacy with knowledge, problems arise. The first is perhaps best summed up by Carneiro when he states,

New knowledge is undergoing constant metamorphosis. The most important change concerns the transition from objective knowledge (codified and scientifically organized) to subjective knowledge (a personal construct, intensely social in its processes of production, dissemination and application). (Carneiro, 2002:66)

Equating literacy with knowledge is relatively unproblematic if the latter is a static concept. However, if knowledge is ‘undergoing constant metamorphosis’ and is social in its aspect, then literacy must be likewise. Muller (2000:2) believes even more strongly that Carneiro that knowledge is intrinsically social, putting even more pressure on conceptions of literacy that are tied to a knowledge-based definition.

Given these problems, others writers have contended that literacy should be understood not as a ‘state’ which an individual has managed to reach, but instead should be conceived as being a ‘process’. Rodríguez Illera (2004) believes that we should rethink ‘literacy in terms of literate practices rather than seeing it solely as learning to read and write, [see] it as a process and not only as a state, and [emphasize] its multiple character and, above all, its social dimension.’ (2004:58-59)

Viewing literacy as a social process gives rise in the literature to much discussion about social and cultural practices upon which literacy may be predicated. Going back to Scribner and Cole (1981), Rodríguez Illera quotes the authors as stating that, ‘Literacy is not simply knowing how to read and write a given text but rather the application of this knowledge for specific purposes in specific contexts.’ This would seem to allow for Kress’ concern about literacy’s relation to knowledge, whilst allowing for the social context that so many writers on literacy believe to be important.

The ‘proof of the pudding’ in terms of whether someone can be called literate is the production of texts. Allan Luke (in Tuman, 1992:vii) gives a concise overview of the three-step process by which texts are created:

Literacy is a social technology. That is, literate communities develop varied social, linguistic and cognitive practices with texts. These require the development and use of implements, ranging from plumes and ball point pens to keyboards. The objects and products of such practices and tools are recoverable texts arrayed on tablets, notebooks or other visual displays.

The text is co-constructed within a community, it is ‘written’ using one of a number of technologies, and then it is displayed. With this social aspect of literacy comes several issues and problems, not least the ethnocentric problem of being ‘literate’ according to the norms and practices of one community, yet not so according to those in another – even another community speaking the same language. Secondly, it would seem at first glance rather problematic to identify literacy as depending upon the literacy practices of a community. We talk of individuals being ‘literate’, not communities. Third, if literacy is a ‘cultural expression’ (Freire & Macedo, 1987:51-52) then it would be possible to be literate at one point in a culture, but not when the culture evolves and changes.

This first problem is a somewat philosophical one in terms of the problem of ‘other minds’. However, on a more practical level, Welch (1999) has argued that literacy is not just the ability to read and write, but, ‘an activity of the minds… capable of recognizing and engaging substantive issues along with the ways that minds, sensibilities, and emotions are constructed by and within communities whose members communicate through specific technologies.’ (Welch, quoted in Gurak, 2001:9) This interaction, and indeed the ability to do so, is for Welch what makes an individual ‘literate’. Note that this definition is predicated upon technology – whether that be pen and paper or digital technologies such as email. Literacy involves the ability to read and write: merely speaking about and showing and understanding of what one has read does not completely fit the criteria.

The second problem mentioned above, seeing as problematic literacy being dependent upon the literacy practices of a community, is dealt with more easily by thinking of communities of literacy practices. Although Carr (2003) is talking of more generic skillsets in the following, it can easily be applied to literacy and literacy practices:

…there are going to be skills and activities (such as literacy and numeracy) that all need to acquire because no modern person can adequately function without them, as well as skills (of auto-repair and secretarial work) that some but not all individuals will require for particular vocations. (Carr, 2003:18)

Likewise, there are going to be some particular literacy practices – perhaps centering around professions or interests – that are specific to smaller communities, but this does not preclude there being a wider ‘literacy’ that all recognise as being relevant in a generic sense to all of these sub-communities. To be literate, therefore, can mean to build upon the literacy practices of one or more communities, without leading to the absurd conclusion of identifying the communities themselves as ‘literate’.

The third and final problem can be solved rather straightforwardly with a couple of thought experiments. First, imagine that you are taken as you are now and dropped in the middle of a village in a country whose language you do not know how to speak or read. You would not be able to read anything that they had written down, nor write yourself in a manner which they would understand. You would not be ‘literate’ in that community. The second thought experiment is similar, but involves a time frame. Imagine an English monk from the 13th century somehow being transported to modern day England. Although some words in Old English and Latin are similar to their modern-day equivalents, still the monk would struggle to communicate. Not only that, but he would be limited to being able to use – at least at first – those technologies available to him in the 13th century. As a result he would not be fully ‘literate’ in a 21st century sense of the term. Given these two examples, it seems relatively clear that literacy does depend upon culture and has an historical aspect. In fact, it must include the latter for community and cultural cohesion: generations have to be able to communicate with one another effectively!

Some may argue against this stating that an individual is still literate when apart from a community and in isolation. That may be the case, but his or her literacy skills are predicated upon those learned when within a community. The critic may rebutt this argument by thinking up a thought experiment of their own where an autodidact stranded on a desert island teaches himself to read and write by discovering a library. That may be the case but, as Lemke points out, we employ community-constructed social practices even when alone:

Even if we are alone, reading a book, the activity of reading – knowing which end to start at, whether to read a page left-to-right or right-to-left, top-down or bottom-up, and how to turn the pages, not to mention making sense of a language, a writing system, an authorial style, a genre forma (e.g. a dictionary vs. a novel) – depends on conducting the activity in a way that is culturally meaningful to us. Even if we are lost in the woods, with no material tools, trying to find our way or just make sense of the plants or stars, we are still engaged in making meanings with cultural tools such as language (names of flowers or constellations) or learned genres of visual images (flower drawings or star maps). We extend forms of activity that we have learned by previous social participation to our present lonely situation. (Lemke, 2002:36-37)

The three problems relating to literacy being predicated and depending upon the literacy practices of a community, therefore, are solvable. In fact, to try and define someone as ‘literate’ without reference to something produced for another to read would be extremely difficult!

Hannon (2000) points out a distinction between ‘unitary’ and ‘pluralist’ views of literacy. The unitary view, he states, is predicated upon the idea that literacy is a ‘skill’ and that there is an ‘it’ to which we can refer – a single referent,

According to this view the actual uses which particular readers and writers have for that competence is something which can be separated from the competence itself. (Hannon, 2000:31)

In contrast, the pluralist view believes there to be different literacies. Hannon quotes Lankshear (1987) who links social literacy practices with a pluralist view of literacy:

We should recognise, rather, that there are many specific literacies, each comprising an identifiable set of socially constructed practices based upon print and organised around beliefs about how the skills of reading and writing may or, perhaps, should be used. (Lankshear, 1987, quoted in Hannon, 2000:32)

Pluralists believe not only that we should speak of ‘literacies’ rather than ‘literacy’, but reject the notion that literacy practices are neutral with regard to power, social identity and political ideology. By privileging certain literacy practices – intentionally or unintentionally – hegemonic power is either increased or decreased (Gee, 1996, quoted in Hannon, 2000:34). The pluralist conception of literacy is, to a great extent, similar to the postmodernist movement in the late 20th century. Whilst adherents are clear as to what they are against – in this case a ‘unitary’ conception of literacy – it is not always clear what they stand for. Hannon attempts to bring some clarity by appealing to the notion of ‘family resemblence’, much as Wittgenstein (mentioned above) did for the concept of ‘game’.

Hannon, however, does not pigeon-hole himself as either a ‘unitary’ or ‘pluralist’ thinker with respect to literacy. After suggesting that whether theorists prefer unitary or pluralist conceptions of literacy depends upon whether they focus on literacy as a skill (psychology) or as a social practice (sociology), he questions why we need to choose between these two conceptions. ‘A full conception of literacy in education requires awareness of both,’ he states (Hannon, 2000:38).

Although Hannon does not give a name to this ‘third way’ of dealing with literacy, it is difficult to argue against his rationale. Those working more recently than Hannon have indeed given a generic name to the types of literacies mentioned above. Known simply as ‘new literacies’, their study is now a distinct and separate strand of literacy research. They seek, as Durrant & Green put it, to describe a more ‘3D’ model of literacies including ‘cultural, critical and operational dimensions’ (quoted in Beavis, 2002:51). Seeking to describe and, to some extent, promote the new opportunities digital, collaborative technologies afford society, ‘new literacies theorists’ focus on new ways individuals can express themselves. They then debate and try to explain how using these new technologies and methods of expression fit within, or complement, existing literacies.

Most new literacies theorists seek to demarcate a new form of literacy, explain it in detail, and then explain how it is actually an over-arching literacy that contains many sub-literacies. Thus, we have Potter (2004:33) who states, ‘Reading literacy, visual literacy and computer literacy are not synonyms for media literacy; instead, they are merely components,’ but it perhaps most transparently and obviously stated by Thomas, et al. in their definition of transliteracy:

Our current thinking (although still not entirely resolved) is that because it offers a wider analysis of reading, writing and interacting across a range of platforms, tools, media and cultures, transliteracy does not replace, but rather contains, “media literacy” and also “digital literacy.” (2007)

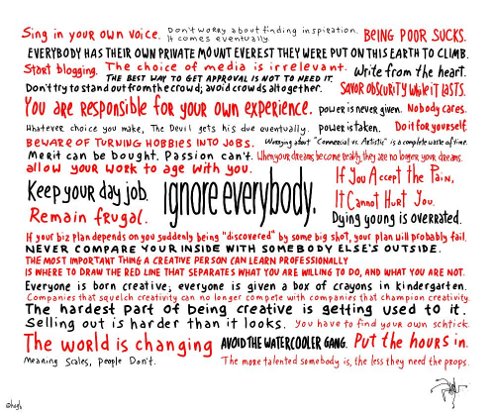

The proliferation of terms, ranging from the obvious (‘digital literacy’) to the horrendous (‘electracy’) seems to be as much to do with authors making their name known as provide a serious and lasting contribution to the literacy debate. So far, although literacy theorists are almost certain about what literacy is not, and which side of several fences they sit, we are not much closer to a definition of what literacy means or consists of in the 21st century.

Bibliography

- Beavis, C. (2002) ‘Reading, Writing and Role-playing Computer Games’ (in I. Snyder, Silcon Literacies: communication, innovation and education in the electronic age, London, 2002)

- Carneiro, R. (2002) ‘The New Frontiers of Education’ (in UNESCO, Learning Throughout Life: challenges for the twenty-first century)

- Gurak, L.J. (2001) Cyberliteracy: navigating the Internet with awareness

- Hannon, P. (2000) Reflecting on Literacy in Education

- Holme, R. (2004) Literacy: an introduction

- Kress, G. (2003) Literacy in the New Media Age

- Muller, J. (2000) Reclaiming Knowledge: social theory, curriculum and education policy

- Potter, W.J. (2004) Theory of Media Literacy

- Rodríguez Illera, J.L., (2004) ‘Digital Literacies’ (Interactive Educational Multimedia, number 9 (November 2004), pp. 48-62)

- Thomas, et al. ‘Transliteracy: Crossing divides‘ (First Monday, 12:12. December 2007)

- Tuman, M. (1992) Word Perfect: literacy in the computer age

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=53f7fc0a-025d-4a6d-a6b8-7a4a323ccb82)