Wake me up when you’ve stopped talking about microcredentials for workforce development

Note: this post had a previous title: Keeping alive the dream of an open, democratic, web-native way of giving and receiving recognition

This is a response to Justin Mason’s excellent provocation / blog post “Thinking Out Loud” About Why Static, Online, Competency-Based Microcredential Courses Are Boring. I want to use this post to get a bit more radical than Justin as I don’t have to include a disclaimer about my employer’s opinions 😉

Justin makes four points in his post:

- Higher education’s primary value isn’t in curating and disseminating instructional content.

- Static, competency-based microcredentials in higher education probably won’t solve the “skills gap.”

- “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.”

- Competency-based micro-credentials focus on workforce development to the exclusion of liberal arts education

Despite having four qualifications from universities, I don’t actually care that much about the continuation of Higher Education in its current form. It’s also been more than a decade since I’ve been employed by a formal education institution. So I want to highlight a point that Justin makes which reminds me that all but the most prestigious universities are about to be eaten alive:

In theory, we could develop practical microcredentials for all the contexts. But who has the resources to do that? You know who has the resources to at least try? LinkedIn, and huge companies like it. For example, you know who has a vast collection of LinkedIn Learning courses and is now promoting skills assessments to compliment them, and is awarding badges? You know who’s partnering with large higher education systems and other companies to develop microcredentials around LinkedIn Learning? Yup. If you’re developing short, online, static, competency-based courses + microcredentials with the idea that you’ll create a large collection of them, ask yourself if your institution has the resources to build microcredential collections that will compete with LinkedIn Learning’s microcredentials in scope and quality. And then allow yourself to have a good cry.

Dividing up existing courses into bite-size pieces will hasten the demise of Higher Education institutions, especially if they partner with organisations such as LinkedIn. Using a third-party provider to give students access to courses that make them more employable is all well and good, but at some point they will cut out the middleman. Why pay tens of thousands to go to university to get a series of microcredentials you can get from the same provider for less (or while working)?

Universities will realise too late that what they’re selling are experiences and signals. What they’ve got the opportunity to move into is recognition of the unique nature of each learner. So instead of making ever smaller generic credentials, they’ve got the chance to provide bespoke recognition.

I really believe that the next step higher education takes toward making itself more accessible, inclusive, and equitable is through the recognition of life-wide learning. I wager that microcredentials, or something very much like them*, will probably be a big part of how recognition of life-wide learning works. But if microcredentials are understood to be 100% about workforce development, then I worry they’ll contribute to the workforce-ification of public higher education, and that’s something I don’t want to see happen. I wish, oh how I wish, that faculty and administrators who advocate for higher education’s public mission would stop simply identifying microcredentials with workforce development. Instead, I would ask them to consider how microcredentials could be one available tool that helps us extend the reach of public higher education to previously unserved people, as well as extend the lens of liberal arts learning to encompass lifelong and life-wide learning! Seriously, our rapidly changing world needs that lens!

People need income to live, which usually means that they need to work. Most work, but not all work, comes in the shape of ‘a job’ which entails an employer. This does not mean that we need to tailor our whole education system to please employers. As Justin mentions, the ‘skills gap’ is a convenient fiction peddled by large organisations who do not want to spend money on training and development. It’s only recently, after all, that graduates were expected to be immediately ‘work ready’ for employers.

But even if we did want to please employers, the way that Higher Education seems to be approaching microcredentialing seems to be backwards. Instead of creating generic content that then needs to be applied to an area, the world of work requires extremely contextual and domain-dependent recognition of knowledge, skills, and understanding.

[K]nowledge and skills tend to be embedded in contexts. People (okay… mostly my relatives) bemoan higher education for being too abstract. Learning should be practical, they say. What my relatives don’t realize is that an amount of “abstractness” is necessary if you’re developing curricula intended for any and all contexts and learners. Take, for example, an introductory microcredential on project management. The trouble is that project management in the construction industry looks significantly different from project management in the health care industry or software development industry. Even within a given industry, project management will differ from one organization to the next. So microcredential designers must consider tradeoffs. They can either build a “practical” microcredential curriculum that is 80% useful to 5% of their potential learner-consumers, or they can build an “abstract” curriculum that is 40% useful to 80% of their potential learner-consumers (those percentages are made up examples).

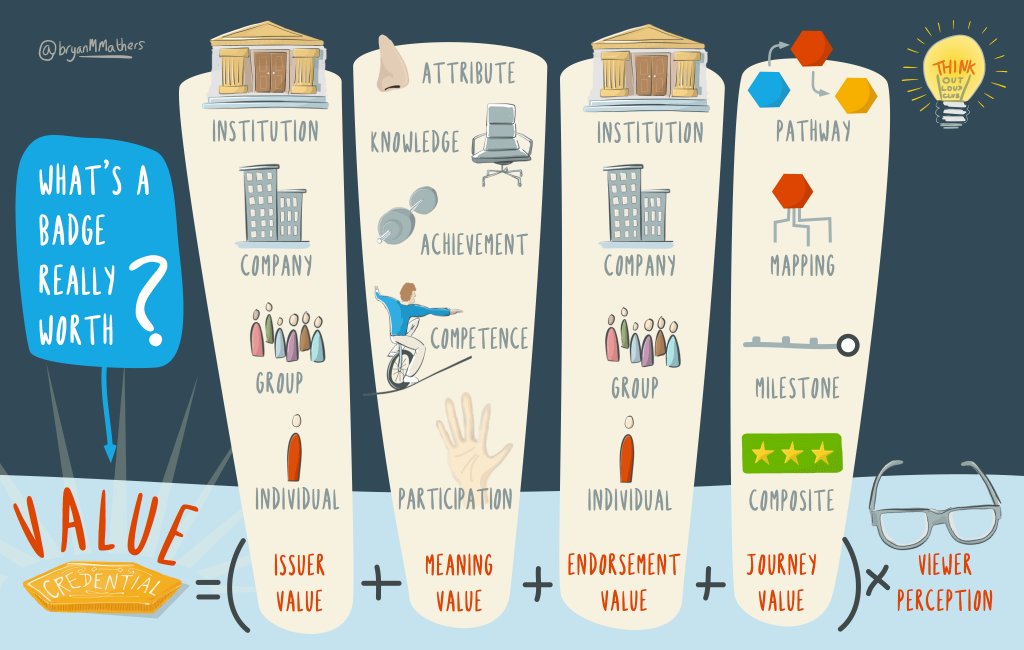

A microcredential itself is not ‘content’ but rather a signal of having learned or mastered something. While a university might want to control the value of the different kinds of credentials it offers, it’s not quite as simple as that. As the illustration at the top of this post shows, there are many facets to take into account. What Higher Education institutions need to bear in mind that, as part of this great unbundling, there is no actual requirement that they are the ones who issue valuable forms of recognition.

The work that I’m involved with at the moment (alongside Justin!) through Keep Badges Weird and the OSN Open Recognition working group involves thinking about what happens when a Community of Practice takes the place of an institution. I think we could see the return of guilds run as a form of co-operative trade union which would recognise and legitimate workers within a given domain. They could push back against the overbearing power of employers. I think it would be massively preferable to the situation in which we find ourselves right now.

Most of the questions that badges have raised over the last 12 years have been ‘trojan horse’ in nature. What do we mean by ‘quality assurance’? How can we do assessment at scale? What’s the minimum viable qualification? In fact, when I was on the original Mozilla Open Badges team, the main opposition to badges came from exactly those kinds of universities that are now jumping on the ‘static, online, competency-based’ microcredential bandwagon. I suspect they’re, either consciously or unconsciously, looking for ways to embrace, extend, and extinguish an open standard to try and firm up their position within the ecosystem.

Perhaps I’m getting older, but I see a lot of issues that on the surface look like they’re about skills and credentialing that are actually deeper and more structural. There are assumptions about power relations baked into every conversation I have had over more than a decade in this area. At some point we’re going to need to have some real talk about that as well. My view, unsurprisingly, is that we need more democracy and autonomy in the workplace, and that this starts with this being practised within our education systems.

For now, though, I’d encourage those who see the world through the lens of microcredentials to read some work that my colleagues and I have done in this area over the last few years. I’d suggest reading these three posts, focused particularly on Open Recognition in the workplace:

- What is Open Recognition, anyway?

- Open Recognition is for every type of workplace

- I got 99 problems, but recognition ain’t one

Once you’ve done that, come and introduce yourself to the KBW Community, start earning some badges for recognition, and see if we can keep alive the revolutionary dream of an open, democratic, web-native way of giving and receiving recognition!