TB871: Responding to change (and junking a lot of perfectly good habits in favor of awkward new ones)

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Systems Thinking, to me at least, is about making strategy to change something within an organisation, or in an environment that contains organisations. As such, the fact that something is going to change is a given.

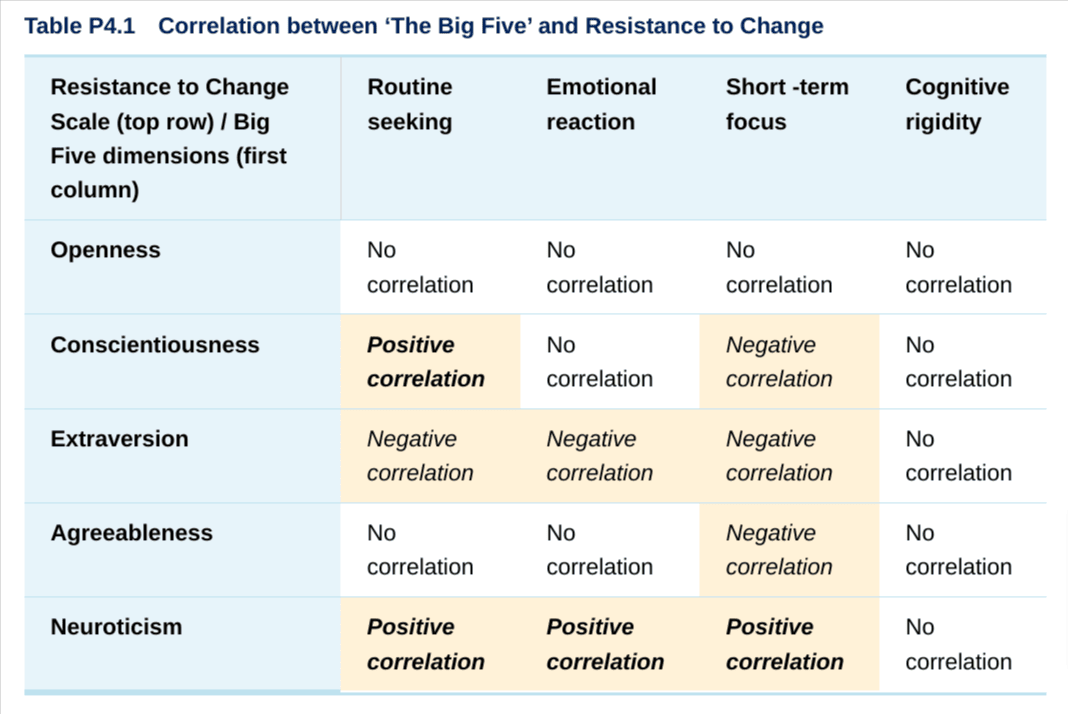

The received wisdom is that “people don’t like change.” But that’s not necessarily true, especially given what I’ve discussed in previous posts about personality and personality differences in teams. The module materials (The Open University, 2020) discuss Oreg’s Resistance to Change Scale and the four factors defining a disposition towards change:

- Routine seeking

- Emotional reaction to imposed change

- Short-term focus

- Cognitive rigidity.

Plotting these against the ‘Big Five’ personality traits leads to some interesting findings:

As you can see, the table indicates that the strongest correlations are observed with extraversion and neuroticism. It suggests that individuals with a tendency towards neuroticism are more inclined to resist change, demonstrating positive correlations with routine seeking, emotional reaction, and short-term focus. On the other hand, those with a tendency towards extraversion show negative correlations with these factors, indicating they are less prone to resistance to change behaviours.

Beyond these strong correlations, the relationships between the Big Five dimensions and resistance to change factors are perhaps more nuanced. For instance, conscientiousness is positively correlated with routine seeking but negatively correlated with short-term focus, suggesting a complex interplay between an individual’s drive for order and their capacity for long-term planning. Openness, meanwhile, shows no significant correlation with any resistance to change factors, indicating that those who are open to new experiences do not necessarily exhibit higher or lower levels of resistance to change.

Resistance to change, though varying in intensity based on circumstances, is a natural trait to some extent in everyone. It includes scepticism, inertia, and ‘reactance’, which is a term borrowed from electronics, and defined as an immediate and unpleasant emotional response to perceived threats to freedom.

While resistance may be more pronounced in some individuals, possibly due to learned behaviours from childhood, studies show that there is no significant gender difference. However, greater resistance to change is more commonly found in younger people compared to older individuals, which I find interesting (and certainly backed up by my experiences as a parent). I think this is probably to do with people who have less knowledge of the world seeking reassurance through routines. But I’m speculating.

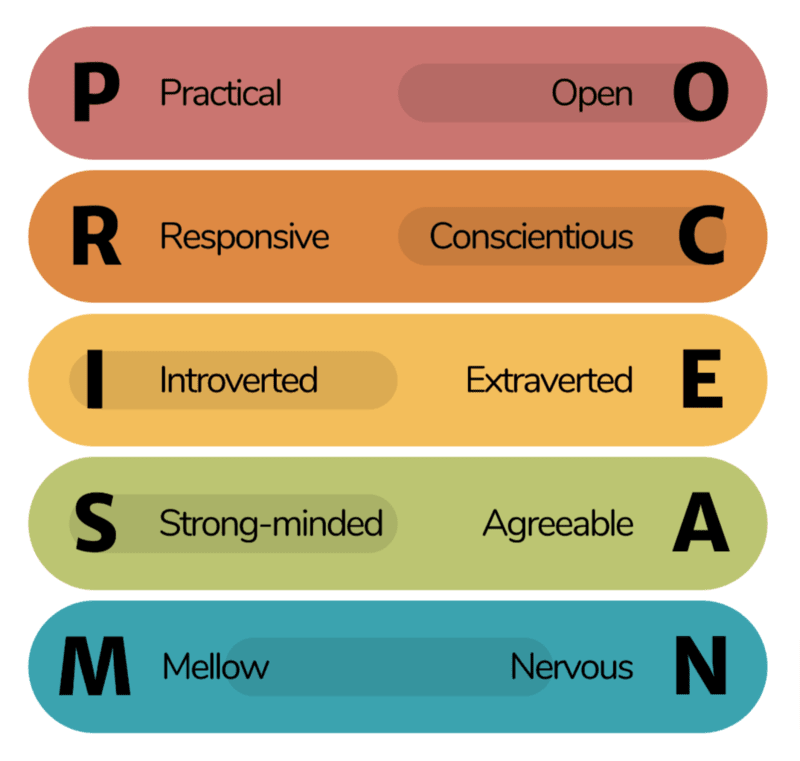

Reflecting on my own life, as someone who is apparently open, conscientious, introverted, strong-minded, and moderate, I have a complex relationship with change. In both my personal and professional life I enjoy strict routines but understand that these are temporary constructs. Regular readers of my blog will be unsurprised to see me reference once again Clay Shirky’s reflection that “current optimization is long-term anachronism” (Uses This, 2014). I’ve been validated and inspired over the last decade by his casual mention that how, “at the end of every year” he “junk[s]” a lot of perfectly good habits in favor of awkward new ones” (Ibid.).

References

- Oreg, S. (2003) ‘Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), pp. 680–693.

- The Open University (2020) ‘P4.2.1 Responding to change’, TB871 Block 4 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261494§ion=3.1 (Accessed 23 July 2024).

- Uses This (2014). Clay Shirky [Online]. Available at: https://usesthis.com/interviews/clay.shirky (Accessed: 23 July 2024).