TB871: Please let me be the last thing I have to write on learning styles

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

As part of this module, we’re directed to look at learning styles. As someone was introduced to them a bit over-enthusiastically during my teacher training, I’ve been skeptical about them my entire career.

However, Stephen Downes, someone for whom I have immense respect, has a more nuanced position. He’s mentioned them many times over the years, with my understanding of his basic position coming from a post 15 years ago in which he stated:

Indeed, the traditional approach’s inability to deal with learning styles is an argument in favour of alternative, learner-directed, approaches in which individual learners can (intuitively) adapt their content and presentation selections to their own preferred learning modalitie, accomodating [sic] their abilities and preferences, or challenging them, as the case may be. (Downes, 2009)

This is why, although I would reject the blunt categorisation of putting learners into particular boxes such as ‘visual’, ‘auditory’ or ‘kinaesthetic’ it is useful for people to know how — at what times and which situations — they prefer to learn.

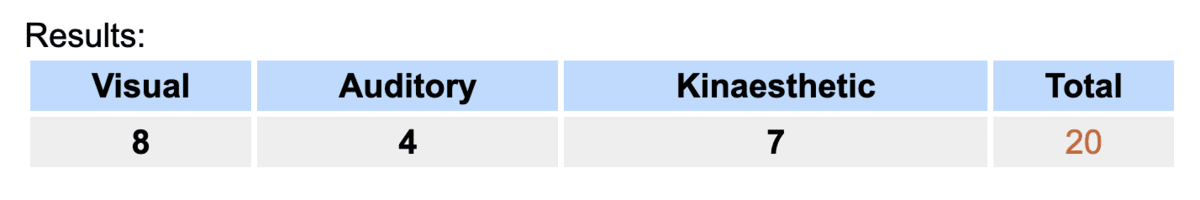

The module materials directed me to a ‘internal representation questionnaire’ which resulted in the following quite unhelpful result. What am I supposed to do with this?

Given that I listen to podcasts on a daily basis where I learn a great deal of things, this feels a bit like horoscopes. As does, to be perfectly honest, the learning styles outlined by Honey & Mumford (1982) and which a client used on a project I worked on a couple of years ago (The Open University, 2020).

- Activists: Fully engage in new experiences, thrive on challenges, and prefer brainstorming and short-term activities.

- Reflectors: Observe and ponder experiences from multiple perspectives, collecting thorough data before concluding.

- Theorists: Integrate observations into logical theories, seeking coherence, rationality, and perfection.

- Pragmatists: Try out practical ideas and techniques quickly, seeking effective and efficient solutions.

That’s fine, but as I said in my post about Belbin and Six Thinking Hats, we need to understand that learners play a role in any given situation. I am not, for example, always and forever more a ‘Reflector’.

We can learn a lot from user research as part of product design here, where it’s common to talk about, for example, “as a learner spending time commuting to and from my job on the subway, I want to be able to learn while navigating a crowded environment.” That may or may not mean that the answer is auditory. It might be flashcards. The point is that context is important. Yes, learners have preferences, but they’re contextual.

From a systems thinking perspective, I think the point of all this is to help us realise that, hey, everyone’s different and so will take a different view on things. They also prefer to describe stuff and receive information in different ways. But as an educator at heart, and someone who’s considered these things over the majority of my career to date, that’s not exactly a revelation.

As I wrote a few years ago, I learn best through frustration; if I care about something, I’ll want to find out more:

Sometimes there’s a perfect YouTube video to watch or article to read, but more often than not it’s a random post on a forum somewhere, or a Reddit comment, or social media post in the middle of a thread. (Belshaw, 2020)

Context is everything, which is why when working with clients it’s good to have a toolbox of approaches. No model is ‘true’ — they’re just either more or less useful in the way of belief. (Spoken as a true Pragmatist!)

References

- Belshaw, D. (2020) ‘Learning through frustration’, Open Thinkering, 7 October. Available at: https://dougbelshaw.com/blog/2020/10/07/learning-through-frustration/ (Accessed: 25 July 2024).CloseDeleteEdit

- Downes, S. (2009). ‘Do Learning Styles Exist?’. OLDaily [Online]. Available at: https://www.downes.ca/post/48662 (Accessed: 25 July 2024).

- The Open University (2020) ‘Descriptions of learning styles’, TB871 Block 4 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261551 (Accessed 25 July 2024).

Image: Danielle-Claude Bélanger