A bit of family history

I spent part of today at my parents’ house with my daughter, their grandchild. She had an English assignment from school which involved find out about relatives who were involved in either of the World Wars.

This led to a fascinating conversation with my parents, which she recorded using an app which gave her a transcription. My parents, either because I’d never asked, or because they’d done some preparation, told her things they’d never told me.

The above is a photograph of my paternal grandparents taken in July 1948 in Blackpool. My grandfather was in the Royal Medical Corps during the Second World War but was a baker by trade. He started smoking due to the war due to the stench of dead and injured bodies. My dad also told me how he’d been strafed by a Messerschmitt despite driving a van with prominent medical ‘red cross’ markings. He only survived because he had a bit of a premonition of what was going to happen and so dived out of the van into a ditch.

My grandfather died of angina in the mid-1980s, meaning I never really knew him. My grandmother, however, lived into her nineties, dying only a few years ago. She was a very matriarchal figure.

I don’t have a photo of him, but my dad also told us about his grandfather, who fought during the Great War. He was on the big artillery guns so wasn’t near the front line, and the only injury he received was to his thumb after getting it jammed in the breech. Apparently his thumbnail grew ‘weirdly’ after that. Having only been around my son’s age when he signed up (17) he was still only in his early forties when the Second World War broke out. However, he was a miner by that point which was deemed an essential service.

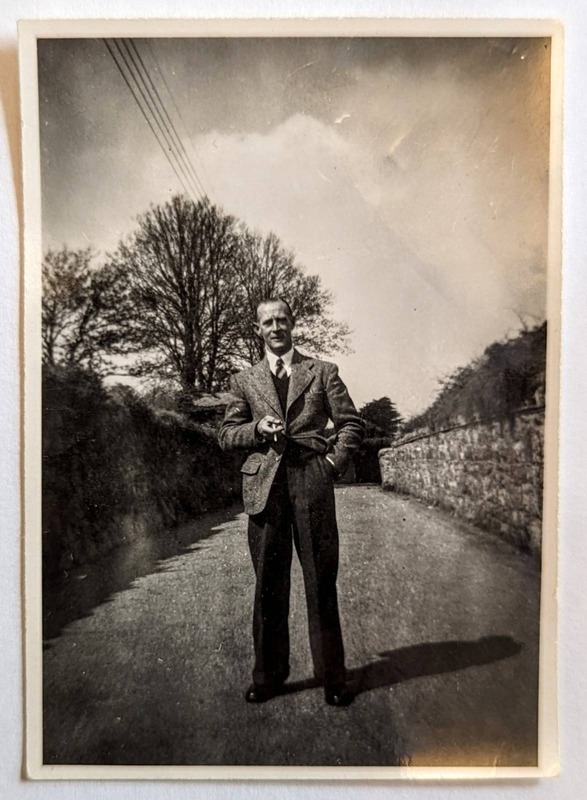

My maternal grandfather is pictured above. He had some significant mental health issues after having what my mum described as a ‘difficult childhood’ and being conscripted as a firefighter during the Blitz. We don’t know a lot about him, but he died of emphysema before I was born. He was in his fifties, and my maternal grandmother was forty when they had my mum, which was extremely unusual in those days.

Although I’d always meant to do it, apparently my sister did actually talk to my paternal grandmother before she died about her family tree. I’m really glad, as although both my parents were only children, their parents and grandparents had plenty of siblings! Some emigrated to Canada, and others to New Zealand. My mother has been in touch with some over the years, but many have passed away.

I found the conversation really interesting and I’m glad my daughter had this assignment. I’m looking forward to following it up at some point in the future.