An ending, a beginning

Of all the human constructs that shape our ways of thinking, chief among them has to be our collective understanding of time. After all, dates, months, and years do not exist objectively and separately from human experience. Birds and insects are not arranging to meet at 9pm on Saturday the 22nd.

For anyone who spent any time in formal education in the western world and then has paid taxes, the question of “when does the year start?” might have at least three answers. We might answer with the calendar year (January), the financial year (April), or the academic year (September).

Elsewhere, more than 20% of the world celebrate Chinese New Year, which depending on the moon, happens in either January or February each year. Jews celebrate Rosh Hashanah, their New Year, usually sometime in September. Endings and beginnings are happening all of the time for different people and in different places.

Using the calendar that I, and everyone else I know, use it’s currently the 15th of November 2021. This is the Gregorian calendar and, stepping back from it a moment makes it all sound a bit odd. For instance, months have different lengths, and then there’s the concept of ‘leap years’… which are worked out thus:

Every year that is exactly divisible by four is a leap year, except for years that are exactly divisible by 100, but these centurial years are leap years if they are exactly divisible by 400. For example, the years 1700, 1800, and 1900 are not leap years, but the years 1600 and 2000 are.

United States Naval Observatory

As Wikipedia’s list of calendars shows, there is a plethora of different ways of organising time — and for different reasons.

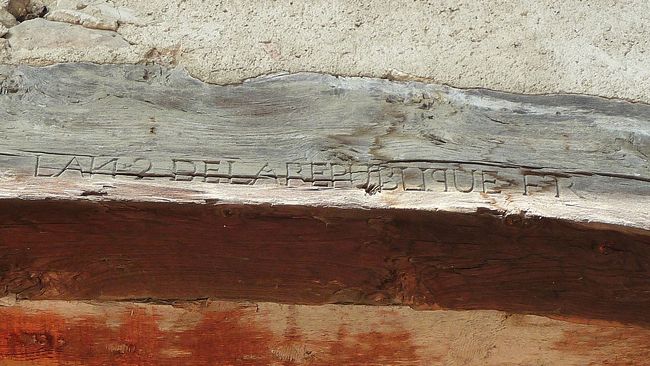

I’ve discussed many times in my presentations that literacy is a form of power. It’s a way of legitimising certain practices, attitudes, and approaches to the world. The same could be said of calendars, which impose an official way of looking at time. This is why the French Republican calendar, the Soviet calendar, and the Era Fascista calendar exist; they offer a revolutionary break with the past, represented by a rending of time itself.

This is all interesting in and of itself, and I could start getting into the decimalisation of days and weeks, but my main reason for mentioning it is somewhat more prosaic. Ever since discovering the French Republican calendar, I’ve been fascinated by the way that months were named after the weather in Paris at that time of the year.

The days of the French Revolution and Republic saw many efforts to sweep away various trappings of the Ancien Régime (the old feudal monarchy); some of these were more successful than others. The new Republican government sought to institute, among other reforms, a new social and legal system, a new system of weights and measures (which became the metric system), and a new calendar. Amid nostalgia for the ancient Roman Republic, the theories of the Enlightenment were at their peak, and the devisers of the new systems looked to nature for their inspiration. Natural constants, multiples of ten, and Latin as well as Ancient Greek derivations formed the fundamental blocks from which the new systems were built.

[…]

The Republican calendar year began the day the autumnal equinox occurred in Paris, and had twelve months of 30 days each, which were given new names based on nature, principally having to do with the prevailing weather in and around Paris and sometimes evoking the Medieval Labors of the Months. The extra five or six days in the year were not given a month designation, but considered Sansculottides or Complementary Days.

Here is the list of months of the French Republican calendar:

Autumn

– Vendémiaire (from French vendange, derived from Latin vindemia, “vintage”), starting 22, 23, or 24 September

– Brumaire (from French brume, “mist”), starting 22, 23, or 24 October

– Frimaire (From French frimas, “frost”), starting 21, 22, or 23 NovemberWinter

– Nivôse (from Latin nivosus, “snowy”), starting 21, 22, or 23 December

– Pluviôse (from French pluvieux, derived from Latin pluvius, “rainy”), starting 20, 21, or 22 January

– Ventôse (from French venteux, derived from Latin ventosus, “windy”), starting 19, 20, or 21 FebruarySpring

– Germinal (from French germination), starting 20 or 21 March

– Floréal (from French fleur, derived from Latin flos, “flower”), starting 20 or 21 April

– Prairial (from French prairie, “meadow”), starting 20 or 21 MaySummer

– Messidor (from Latin messis, “harvest”), starting 19 or 20 June

– Thermidor (from Greek thermon, “summer heat”), starting 19 or 20 July

– Fructidor (from Latin fructus, “fruit”), starting 18 or 19 August

We live about seven lines of latitude north of Paris, but the above is not too far off in terms of a description of the weather where we are. I guess that’s particularly true as climate change warms the planet, meaning that weather which would have been ‘normal’ slightly further south than us in 1792, becomes the ‘new normal’ here in 2021.

More than anyone else I know, the seasons have a great affect upon my energy levels and disposition towards the world. Sometimes I wish it weren’t so, but I am not a robot. I’ve learned to embrace it, giving myself a break and expecting great things of myself at other times of the year.

According to the French Republican calendar we’re almost at the end of Brumaire. I would like to say publicly that Brumaire can get very firmly into the sea. I am looking forward to Frimaire, and then Nivôse starts on (or around) my birthday. But the real action starts in in the month of Germinal, towards the end of March.

Coincidentally, Germinal is also the name of Émile Zola’s masterpiece, an “uncompromisingly harsh and realistic story of a coalminers’ strike in northern France in the 1860s”. It’s one of my favourite novels.

Vive la révolution!

Image CC BY-SA Divadwg

I had Monday and Tuesday this week off school. I had a cold, felt lousy, and felt my recently-self-diagnosed SAD (

I had Monday and Tuesday this week off school. I had a cold, felt lousy, and felt my recently-self-diagnosed SAD (

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=59d176c7-3bcd-4049-95f6-4445d2176e89)