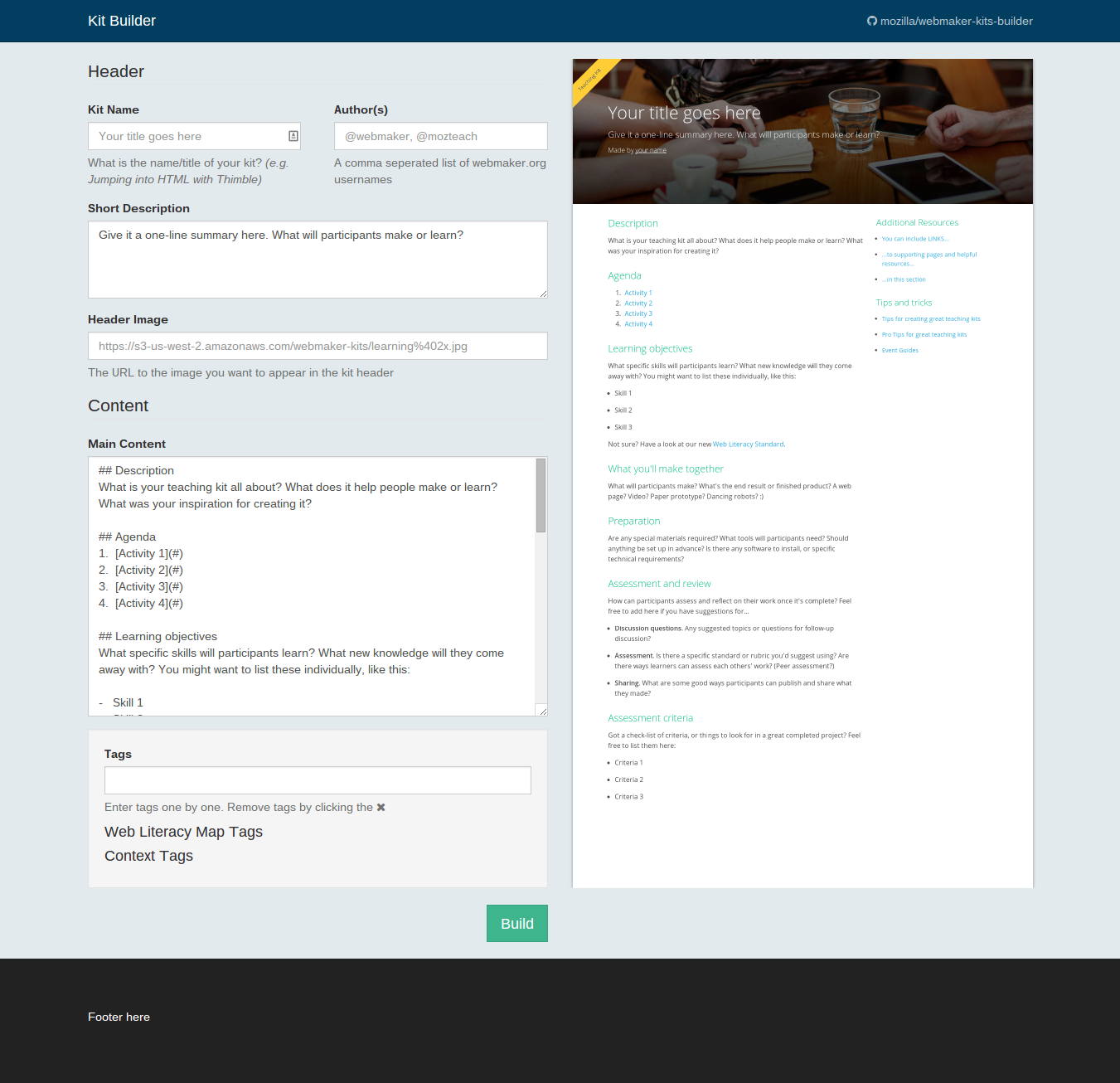

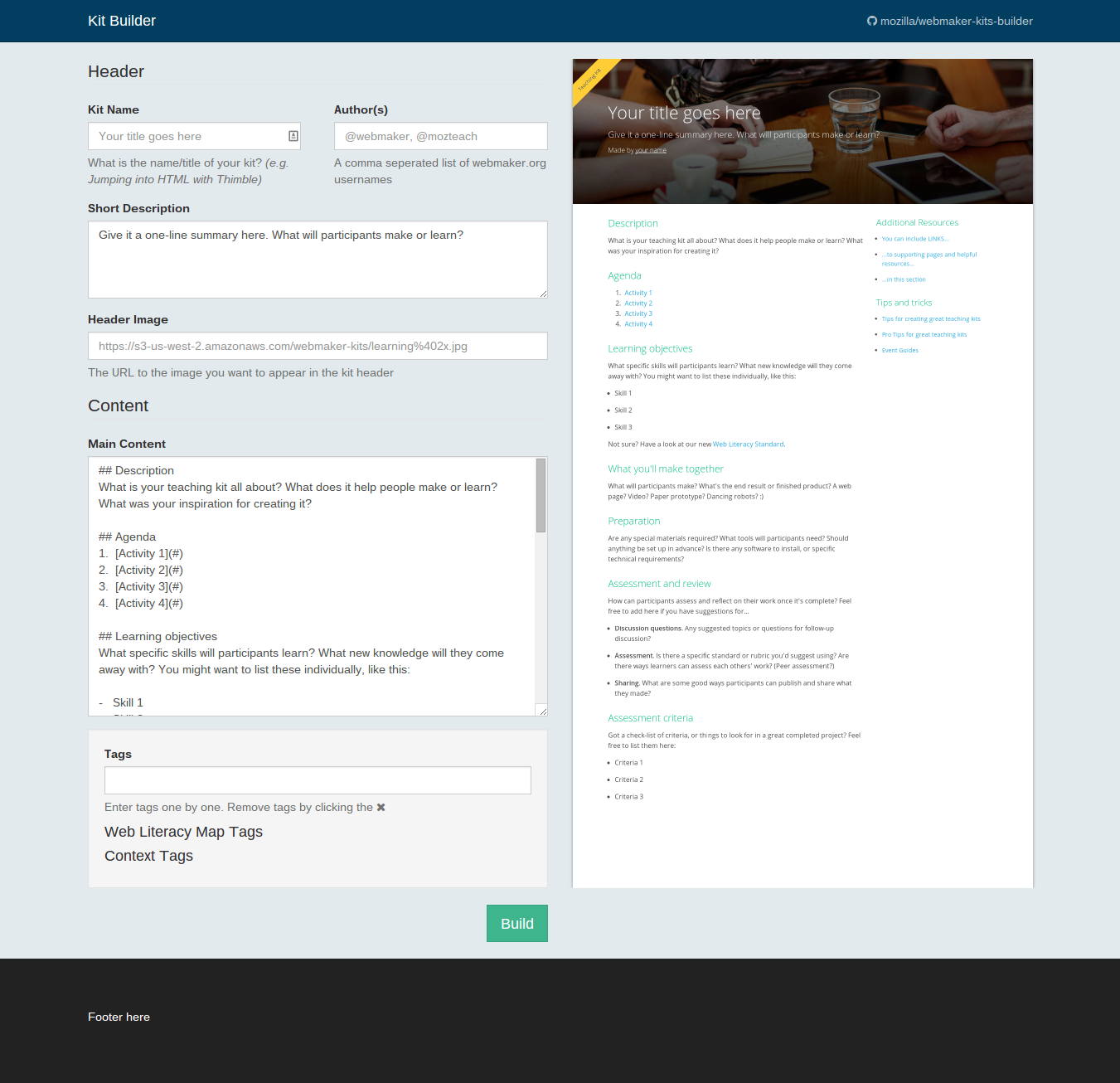

Note: this is one of those blog posts where I use one thing as a convenient hypocrisy to talk about another thing. Kind of like Jeremy Clarkson’s car reviews, I guess. If you just want to get to the meat, check out my very talented colleague William ‘FuzzyFox‘ Duyck’s new pre-alpha Webmaker prototype: Kit Builder. The rest is tangential, to say the least.

I’m increasingly convinced that there’s a gaping hole that someone will soon fill when it comes to organisational effectiveness. Before I describe that, I need to talk about some of the basic technology-related things that organisations need in this day and age in order to be effective.

OK, so I’m simplifying massively for rhetorical effect, but here’s three things I think you can’t do without – no matter what size of organisation you’ve got. These may be more formal or less formal, but you need them unless you plan to descend into chaos.

1. Issue tracker

I wrote about this in a bit more detail in a recent post, but basically what I mean is that you need some way for people to raise ‘bugs’, ‘issues’, ‘tickets’ or whatever you want to call them, and get the whatever the problem is fixed.

Examples: Trello, BugZilla, GitHub

2. Resource tracker

Much as I hate the term ‘human resources’, I’m going to use it here because it’s useful. Other people in your organisation should know where things and people are. Or, if that’s not possible for whatever reason, they should at least know you (or a room’s) free/busy status. It’s all about co-ordination, really.

Example: Google Calendar, Basecamp

3. Knowledge base

The best organisations I’ve worked in have had wikis. It’s all very well knowledge residing ‘in networks’ but that does build new knowledge. That only comes when a community (not a network) of people come together to intentionally build something. That’s where the magic happens. You don’t have to use a wiki, of course, but that’s what I’ve seen work best, time after time.

Examples: PBworks, Mediwiki

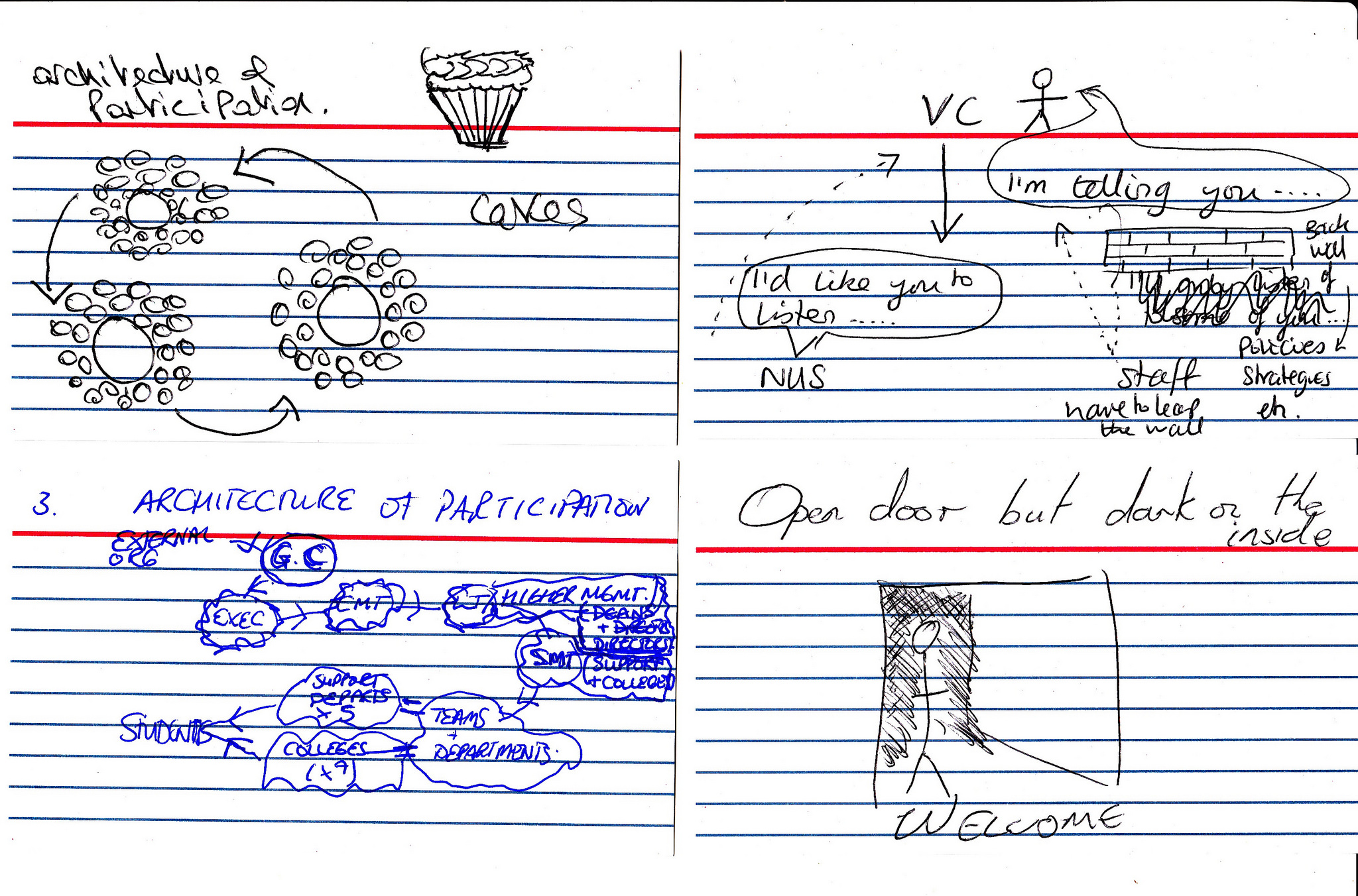

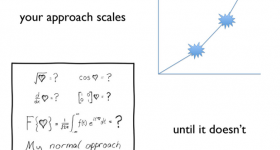

So, coming back to the ‘gaping hole’ I mentioned earlier, what do you do when one organisation has all of this in place, and another one doesn’t? Or… even if both organisations have adequate systems, but those systems don’t ‘talk’ to one another. At the moment, that’s where the friction comes, and that’s why there’s well-paid people all over the world who are friendly ‘go-to’ people and help paper over the cracks of relationships between organisations potentially fraught with misunderstandings.

You’ll not hear me say this often, but what we need is a technical (but simple) solution to this mess. A way in which organisations can work together for unspecified periods of time without causing problems, resentment or internal issues for their own setup. I guess it’s a kind of souped-up version of what Jon Udell was trying to achieve with the Elm City project.

What we don’t want are de facto standards like “let’s just all go 1:1 with iPads!”. Or, why don’t we all use Microsoft Office! Or even, “everyone should use Google Apps!”. We tried that, folks. It fails.

But what on earth has this got to do with Kit Builder, a pre-alpha prototype for educators who want to make teaching kits? Well, I’m getting to that. Let me just make a quick point about ‘means of production’ first.

As Marx didn’t write, but someone on Wikipedia helpfully did:

The means of production can be simply described as follows: in an agrarian society the soil and the shovel are the means of production; in an industrial society, mines and the factories; and in a knowledge economy, offices and computers. When used in the broad sense, the “means of production” includes the “means of distribution” such as stores, the internet and railroads.

I’m butchering Marx’s work here, but the point I’m trying to make about Kit Builder is that it’s not just another capitalist company offering you a proprietary silo. Even in pre-alpha, it’s a pretty straightforward way to create high-quality resources. You’re in control of everything. You can copy and paste the HTML into Notepad, for goodness’ sake.

Once you’ve created a resource using Kit Builder (or Webmaker in general), you get all of these benefits:

- Hosted on the web (accessible everywhere)

- Remixable (by anyone)

- Open format (can be used on any system)

I wasn’t sure how to put this as a bullet point, but you also don’t get the crazy situation where Sue has one program which spits out files that are incompatible with Bob’s program. And, because there’s no downloading/uploading of files, we don’t end up with filenames like:

Billy's presentation FINAL (use this one!) NO THiS ONE (final version) v2.ppt.docx.pdf

At the moment the text boxes in Kit Builder require you to use Markdown to format your text. I’d suggest we keep this as a feature. Markdown is a human-centric way to enter text that is then rendered as a web page. It’s easier to understand if you realise that HTML stands for ‘HyperText Markup Language’ and is machine-readable code for rendering web pages. Markdown on the other hand, is much more human readable, and allows you to include arbitrary HTML if necessary.

I’d very much encourage you to explore Kit Builder. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from my 18 years on the web so far is that open wins the long game. Shiny, pretty closed things come and go, but if you’re in it for any period of time, bet on open. And if you need to level-up your skills, don’t just sit on your hands, join in with Webmaker Training.

And finally, if you’ve got a way to build something that talks to lots of different systems and provides a human-readable layer, please do it. Do it now.