I think I must have been about eighteen when I started getting migraines.

I’d applied and got through the first few stages for having the Royal Air Force sponsor me through university. In return, I would have to agree to ‘sign up’ for sixteen years after graduation. It’s a fact that I’m reminded of as it’s only now, as a 37 year-old, that I would be returning to civilian life.

After a successful interview with the Wing Commander at RAF Linton-on-Ouse, he asked if anything had changed with my application since filling it in some six months prior to our meeting. It was a routine question, but one I felt I had to answer honestly.

I disclosed that I’d just started suffering from migraines with visual disturbances (‘aura’). He raised an eyebrow, walked over to a cabinet and pulled out a large binder. Finding the relevant entry, he read it to me. I already knew that I couldn’t be an RAF pilot after needing corrective lenses from the age of seventeen. Now, he told me, because every type of migraine can be triggered by stress, a position in Fighter Control was now also out of reach.

Given my feelings about war and nationalism these days, I suppose that I ‘dodged a bullet’ there (so to speak). At the time, though, I was bitterly disappointed. So began my life as a migraineur.

In today’s Observer, Eva Wiseman writes about migraines after news that the American FDA has approved a potential ‘cure‘ to migraines:

The newly-approved drugs follow a much more targeted approach [to previous efforts]. Back in the 1980s, researchers investigating migraines’ root causes zeroed in on the CGRP, a molecule that regulates nerve communication and helps control blood vessel dilation. Scientists found that those with migraines had markedly more CGRP molecules than those without. They also found that if they injected CGRP into people who were known to get migraines, that alone would trigger one. People without a history of migraines could get the same injection without experiencing a headache.

However, like Wiseman, I’m a little skeptical about all this; I’m not sure migraines can be fully separated out from the migraineur:

My personality is curled around the knowledge of a migraine, like the fruit of an avocado and its pit.

It’s difficult to explain what it’s like to have a migraine to someone who has never had one. They’re whole-body experiences and, although people often point to the crushing headaches, it’s actually impossible to separate them out as a distinct ‘event’. They come at you like waves, gentle at first, but increasing in ferocity.

It was quite by accident that I came across a book a few years ago that had a direct and lasting effect on my life. The late Oliver Sacks’ book Migraine made me realise that, for better or worse, migraines are just part of who I am. He draws on clues from history about migraines, as well as his own clinical experience:

“You keep pressing me,” he said, “to say that the attacks start with this symptom or that symptom, this phenomenon or that phenomenon, but this is not the way I experience them. It doesn’t start with one symptom, it starts as a whole. You feel the whole thing, quite tiny at first, right from the start.… It’s like glimpsing a point, a familiar point, on the horizon, and gradually getting nearer, seeing it get larger and larger; or glimpsing your destination from far off, in a plane, having it get clearer and clearer as you descend through the clouds.” “The migraine looms,” he added, “but it’s just a change of scale—everything is already there from the start.”

Curiously, there are significant benefits to being a migraineur. These include mild synaesthesia, the ability to see more visually things like historical dates that others find more abstract, and being finely attuned to the weather. There’s also some evidence that migraineurs are less likely to have huge egos.

Sacks writes that:

Transient states of depersonalisation are appreciably commoner during migraine auras. Freud reminds us that “… the ego is first and foremost a body-ego … the mental projection of the surface of the body.” The sense of “self” appears to be based, fundamentally, on a continuous inference from the stability of body-image, the stability of outward perceptions, and the stability of time-perception. Feelings of ego-dissolution readily and promptly occur if there is serious disorder or instability of body-image, external perception, or time-perception, and all of these, as we have seen, may occur during the course of a migraine aura.

Yet these various upsides for the migraineur can’t be separated from the huge downsides: visual disturbances, the loss of muscle tone, crushing headaches, and an unshakeable feeling of anxiety and depression.

It took me years to pinpoint the triggers for my migraines. Can you imagine the process that I had to go through to discover that the natural food colouring Annatto is guaranteed to bring on an episode? No Coca-Cola, cheap custard, or Red Leicester cheese for me! One time, when I was working as a teacher, my wife had to pick me up and take me home after I confiscated a bag of sweets from a child, ate one, and within minutes started seeing huge jagged shapes in my peripheral vision.

Karma.

These days, I’m more clued-up on the small changes that happen to my mind and body in the 24-36 hours before my first visual disturbance: I notice my body losing muscle tone; I start biting my nails; I want to be alone. It’s no coincidence that I’m writing this blog post in a room by myself with chewed-off nails. I’m expecting the aura anytime soon.

Wiseman describes her visual disturbances as:

[A] flickering blind spot in the centre of my vision. It starts small, a spinning black penny in the middle of a page. I slump in my seat as it spreads darkly over my sight like jam, and I can’t see, or think, or entirely understand speech. It’s the film melting in my projector – it’s a bit like falling.

My migraines are nowhere near as frequent or intense as they used to be. I avoid triggers such as specific food and drink, stay away from fluorescent lighting, ensure I get enough sleep, and make sure I drink enough.

When I worked at a university, my migraines were bad enough to find myself on the disability register. These days, they’re much more manageable, for three reasons:

- Medication — after many failed experiments in my twenties with preventative medication, I’ve discovered Rizatriptan Benzoate. These wafers, so long as I take them within the first few minutes of aura, mean I can get on with my day.

- Working from home — this has had many other benefits, but from the point of view of my migraines, it means that they no longer force me to take a day off work. If I have a migraine in the morning I can, so long as I take my medication, get back to work in the afternoon.

- Exercise — while I have to ensure I don’t become dehydrated, running, swimming and going to the gym help me not only with migraines in particular, but mental health more generally.

However, as the RAF Wing Commander correctly noted, stress is always a trigger of migraines. So, in a sense, I’m quite glad that my body has a very obvious system to force me to rest. I’ve had to come to terms with the fact that intense, high-stress environments aren’t places where I can thrive.

I want to finish with a quotation from Eva Wiseman’s article:

Half of me knows my life would be simpler if I concentrated harder on looking inwards, and took on the part-time job of doctors’ appointments and pills. But the other half, the one that enjoys the sleepy curiosity of life with a migraine and those three long days of magical thinking, is less willing to try and define what is migraine, and what is me.

We’re often told to listen to our bodies, but in a very real sense, I don’t have much option. I’m not sure where my migraines end, and I begin.

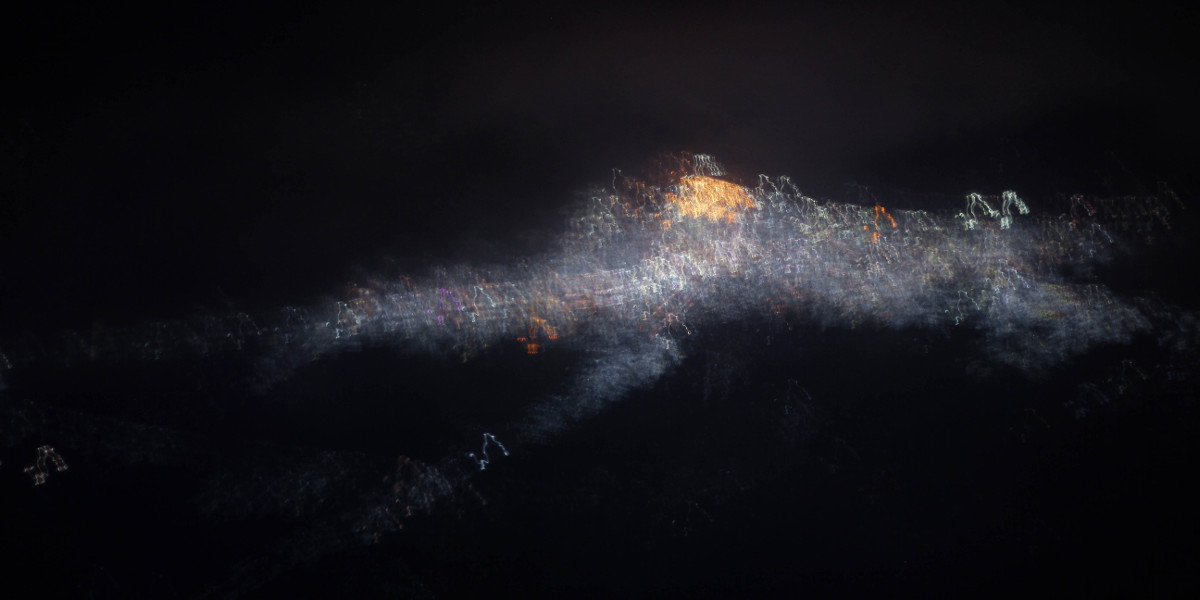

Image by Lizzie at Unsplash