TB871: A Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP) heuristic

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

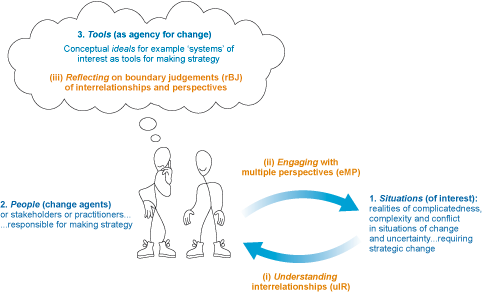

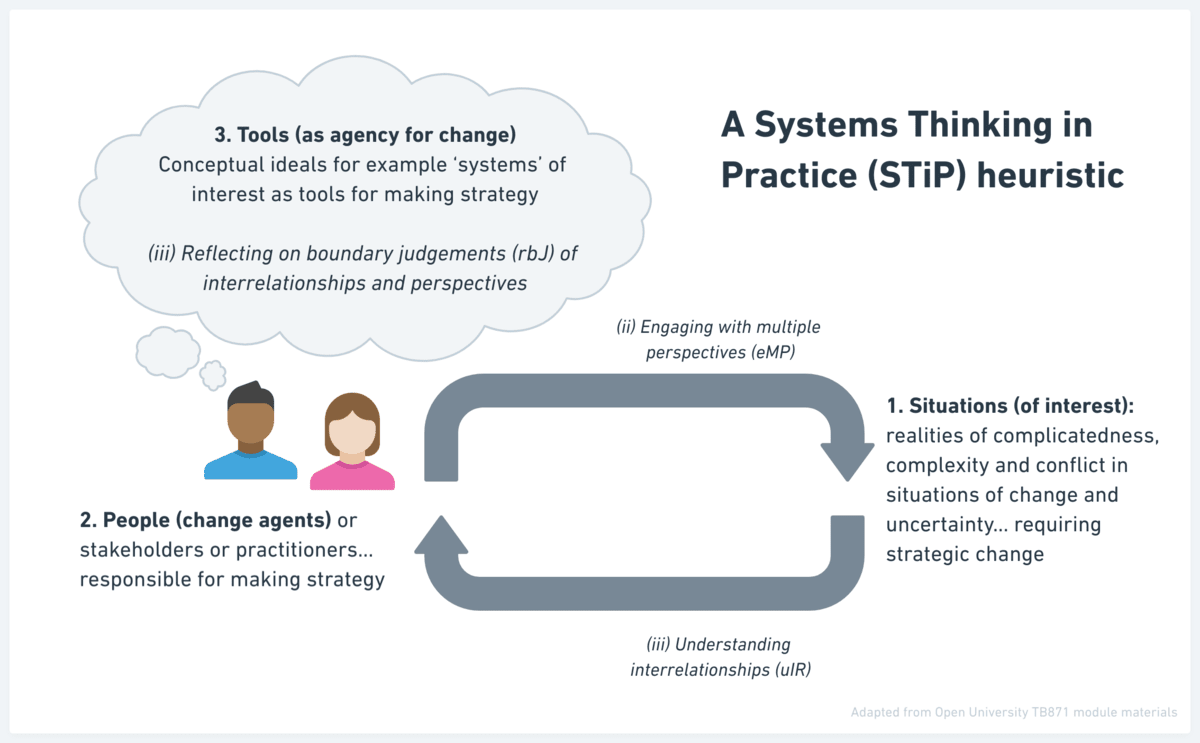

There are three core activities with Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP):

- Understanding interrelationships (uIR)

- Engaging with multiple perspectives (eMP)

- Reflecting on boundary judgements (rBJ)

These three activities can be translated into a learning system, or ‘heuristic’ which is presented in the module materials in the following way:

Unlike TB872, this module doesn’t have such great diagrams. I’m not so good at making them, but I can’t live my life looking at this one repeatedly! So I’ve recreated it:

There is a video associated with this task (Activity 1.13) which refers to the three areas of this diagram as:

- Events

- People

- Ideas

This is perhaps a more intuitive and easy-to-remember way of referring to the parts labelled Situations, People, and Tools. Here’s an extended quotation from the transcript to the video which helps explain the STiP heuristic:

Real world situations are often rendered intuitively as systems, such as the health system, or the financial system, or an ecosystem. Such renderings as systems can be a useful means for then engineering change. So for example, messy financial affairs might be more formally rendered as a budgeting system, which has clear inputs and outputs that might be more easily managed.

The danger is in fooling ourselves that such rendered systems are the actual reality. It’s confusing the map as a system for the actual territory, the reality of the situation. Like any map, much is left out.

[…]

A starting point for a systems thinking approach is working with complicated and complex issues. So systems thinking might be regarded as an endeavour to render complicated, complex, conflictual situations into bounded, conceptual construct, that is, systems for analysis and design, or more specifically, using systems for making strategy. The Systems Thinking in Practice heuristic, or a STiP heuristic as we will call it from now on, is one such learning system; a mental model or idea used as a device for learning about situations of interest and making a strategy to transform them into something better.

(Open University, 2020)

The rest of the video goes on to explain the difference between ‘complicatedness’ (which I don’t think is an actual word?) and ‘complexity’ and also defines a ‘wicked problem’. I’ve summarised these below:

- Complicatedness refers to situations that have many parts that need to be arranged in a certain way. Although it might be tough to solve, it can figure be figured it out with enough expertise or detailed analysis. For example, fixing a broken car is complicated because it requires specific knowledge about the car’s parts and how they work together.

- Complexity relates to a situation is one where everything is interconnected and changes can happen unexpectedly as a result of these connections. Small changes or actions can have big, unpredictable effects. For instance, the stock market is complex because many unpredictable factors can affect stock prices. See also the butterfly effect.

- Wicked problems are tough issues that are difficult to solve because it involves incomplete or contradictory information and changes depending on how people perceive it. These problems are tricky because they are not just hard to solve; they are hard to define. For example, climate change is a wicked problem because it involves many factors and opinions, and solutions are not straightforward.

In addition, a mess is when several complicated and complex issues are all tangled up together, making it hard to see where one problem starts and another ends. Messes are chaotic and hard to sort out because solving one problem might affect another part of the mess. A city’s transportation system can be a mess because it involves roads, traffic laws, public transportation, and the behaviors of thousands of people.

I’m composing this in my local library, run by Northumberland County Council. It’s housed within the new leisure centre. Earlier this week, I was at a Design Sprint session as part of the Thinking Digital conference which was run by members of the digital team at the council. The situation we chose to address as a team was library provision, with visitor numbers going down.

Right now, as I’m trying to work, there is a group of older people meeting in the study space as part of a social group. They’ve having coffee and tea, which is not usually allowed in this space. Given the noise, I’ll probably end up decamping to a coffee shop and may not return on a Friday. This could be seen as a small example of a ‘mess’ which would also involve opening hours, underfunding, and even popular conceptions of what libraries are for.

In fact, come to think of it, this might be a good topic to focus on for my assessments for this module. I shall ponder that further… 🤔

References

- The Open University (2020) ‘1.3.3 A systems thinking in practice heuristic’, TB872 Block 1 Systems and Strategy [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261477§ion=4.3 (Accessed 17 May 2024).