TB872: Bawden and living as a constant process of learning

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Next on the list of systems thinkers to deal with in this module is Richard Bawden, who (oddly) doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. It’s weird how ‘notability’ works on that site. His background is in education and sustainability, particularly in a rural Australian context.

Bawden was part of the ‘Hawkesbury approach’ which includes other Australian academics such as Ray Ison and Jim Woodhill. Ison is one of the authors of this module and a professor at the Open University. This post draws on a video in the course materials (Open University, 2021) and a chapter in the book Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice (Blackmore, 2010).

By way of introduction, Blackmore mentions that “two distinguishing factors of the Hawkesbury approach are that epistemology and ethics are valued… as important to learning” (Blackmore, 2010, p.36). In other words, different types of knowledge are valued, and there is a ‘critical’ element to the approach. It’s a good example of systemic praxis, that is to say people blending theory and practice.

The book chapter, which was originally an invited plenary paper to a conference which took place in 1999, includes quite a few diagrams. To use a goldilocks metaphor, some I find too simple, some too complex, and some ‘just right’.

Let’s begin with the video in the course materials, in which Bawden talks about three levels of learning:

Well, I’ve found a marvellous model of learning back in the early 1980s by Karen Kitchener. And she argued that there were really three ways, three levels if you like, of learning. There was learning about the matter to hand, there was learning about how we learn about the matter to hand, and there was learning about the limits to learning. And she labelled these cognition, metacognition, and epistemic cognition.

So for me, transformation is at any or all of those levels, which means that we change what we do as a result of the way we answer the questions at those three levels. So “what is the situation around me meaning to me?” would be the matter to hand, and then how I deal with it. At the meta level, it’s “how am I dealing with the way I am dealing with the issue?”, what you might call methods. And you could contrast, for instance, a scientific way of looking at something with a religious way of looking at things, which are two meta questions.

And then at the epistemic level, transformation at that level means that I expose my worldview, my set of beliefs and values, to self-critique. And then if I find them inadequate, then the transformation occurs at that level. And in my opinion, higher education should be, should be epistemic cognition.

In other words, we should be really trying to deal with how we make sense of the way we make sense. And that sounds philosophical, and in some ways it is. But it’s a profound question. So higher education, really, is about the way what we know is limited by how we go about knowing and valuing.

(The Open University, 2021)

Bawden is a proponent of experiential learning (i.e. learning by doing) which he sees as “adaption to change, based on a rigorous process of transformation” (Blackmore, 2010, p.47). Reflecting on this experiential learning Bawden calls ‘epistemic cognition’ after Kitchener, mentioned in the above quotation. “It is through epistemic learning,” he says, “that we learn to appreciate the nature of the worldviews and paradigms which we hold as the contexts for what and how we know” (ibid.).

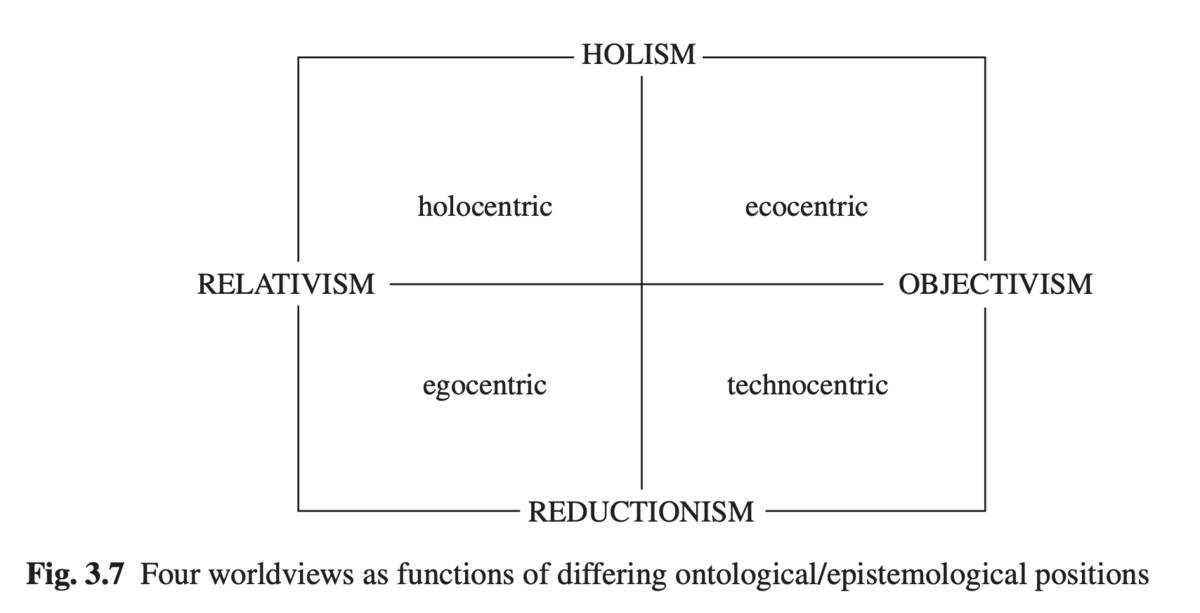

The above diagram is a simple framework with the vertical axis reflecting different ontological positions: “the idea that one either accepts the irreducible wholeness of nature and other systems (holism), or one does not (reductionism)”. Epistemological differences are represented by the horizontal axis, with “one either accept[ing] that there is ‘a permanent, ahistoric matrix or framework to which we can ultimately appeal in determining the nature of rationality, knowledge, truth, goodness, or rightness’ (objectivism) – as Bernstein (1983) put it – or we do not (relativism)” (ibid., p.48).

One of the key points that Bawden wants to get across is that of emergence, and that, as Heraclitus pointed out when talking about a river, not only does it change, but we change too:

[I]f learning is the process by which we make sense of the world around us in order to adapt to it or adapt the world, then the way we live is determined, essentially, precisely by that. So the whole point about living is a constant process of learning. And at the base of all of that is the notion of improvement or development. So there is this constant idea that because the world is constantly changing, we too have to constantly change. And so the way we live, our lifestyle, our well-being, is in the end related to the way we make sense of the world about us.

(The Open University, 2021)

Bawden’s context was rural communities dealing with “immensely complex dynamic[s] and slowly degrading environments – socio-economic politico-cultural and bio-physical – in which they increasingly recognised they were deeply embedded” (Blackmore, 2010, p.39-40). The Hawkesbury approach is much more generally applicable, however, and has been developed into Critical Social Learning Systems (CSLS).

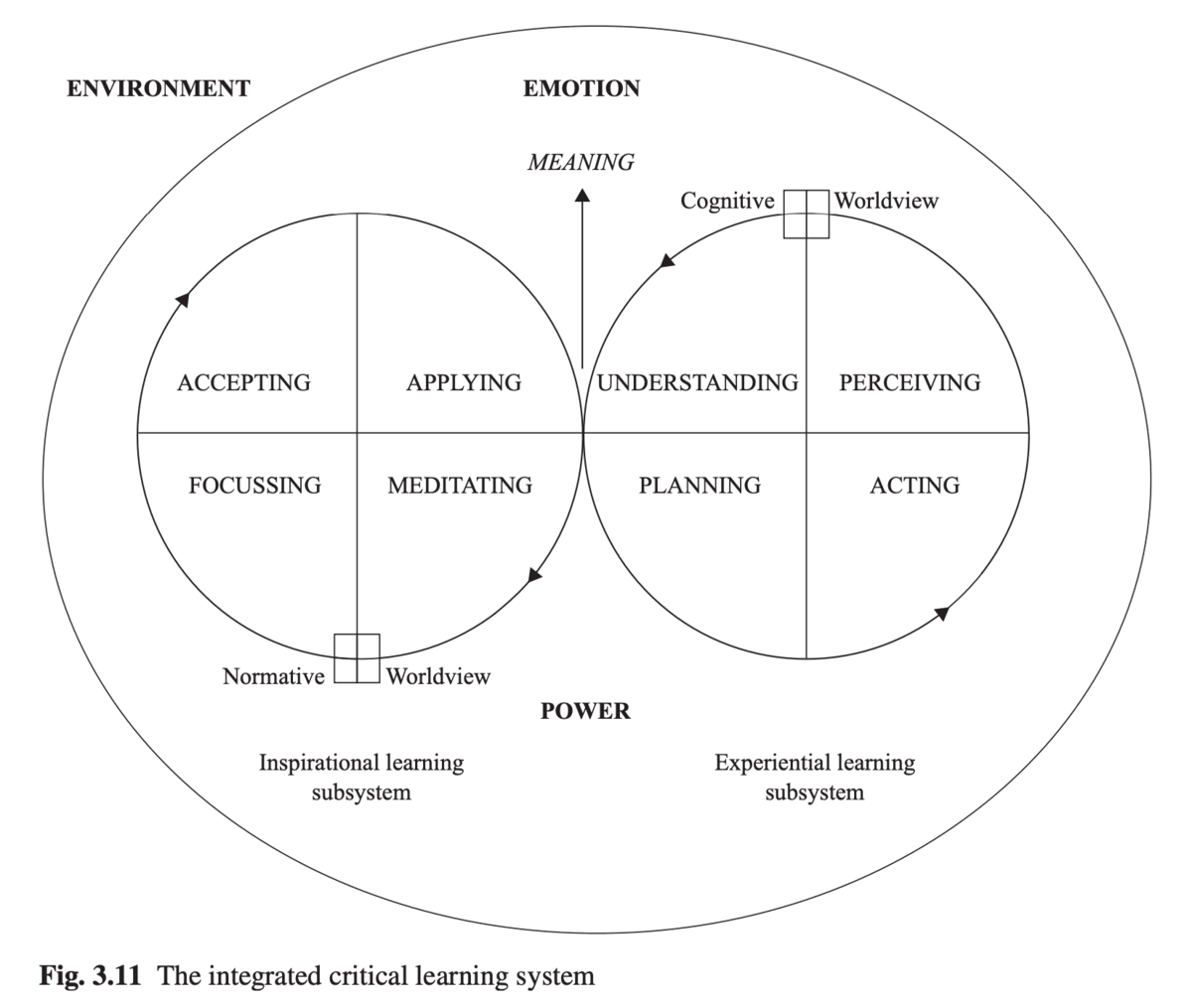

It’s perhaps a function of me being new to this area, but I find the following diagram a bit… much? It’s an attempt to integrate everything discussed in the chapter, which is itself an overview of work which has happened over a number of years. It includes elements of Kolb‘s learning cycles, Vickers‘ appreciative systems, and it even gives a nod to Habermas in terms of power.

Thankfully, Bawden notes that “as with any conceptual model it is vital to remember that the ‘map is not the territory'” so the above diagram is “just that: An image, a mental construct, which has been generated through the application of theory and insights to help create meaning from real world experiences, which have in turn, helped in the modification of those theories and the creation of fresh insights” (ibid., p.53).

Although I find this diagram somewhat confusing, I suppose it’s in the realm of what I would call ‘creative ambiguity‘ and makes sense to those who have studied it enough. I’ll end with Bawden’s checklist of what consitutes an ‘effective learning community’:

In its application, [the Hawkesbury approach] suggests a series of important factors to consider whenever the establishment, development and evaluation of a learning community is being mooted. It illustrates a number of key aspects of ‘social learning’ indicating some of the domains and dynamics that need to be considered. These are worthy of review under the rubric of an effective learning community as one which:

- Has achieved a sense of its own coherence and integrity.

- Contains a requisite level of variety and diverse tensions of difference which are essential for its own dynamic.

- Is clear about its purpose and the influence of this on the boundary of its concerns and indeed its structure.

- Combines both experiential and inspirational learning processes in its quest for meaning for responsible action.

- Is conscious of meta and epistemic cognition, and of the influence of both cognitive and normative worldviews as frameworks for the way meaning is created.

- Is critically aware of its own emotional ambience, and competent at the intelligent management of those emotions.

- Is aware of the emergence of properties unique to different levels of its own systemic organisation, just as it is to the dynamics of chaotic change and the potential of property emergence following reorganisation.

- Appreciates the nature of the environments (suprasystems) in which it operates, and is conscious of both constraining and driving ‘forces’ in that environment.

- Is critically conscious of its own power relationships and those which exist between it and the environment about it, and knows what influence this has as a potential distorter of communication.

- Is self-referential, critical of its own processes and dynamics, and capable of

self-organisation in the face of continual challenge from its environment.- Exhibits leadership as well as meaning as an emergent property.

This ‘checklist’ of systems’ characteristics provides a framework for the sort of conversations and discourse which guide a community which is intent on improving its own capacities for learning its way into better futures.

(ibid., p.54)

References

- Blackmore, C. (ed.) (2010). Social learning systems and communities of practice. London: Springer. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2.

- The Open University. (2021). ‘3.3.4 Bawden: critical social learning systems’, TB872: Managing change with systems thinking in practice. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2171593§ion=3.3.4 (Accessed 25 February 2024).

Image: DALL-E 3