I’m (re-)writing my first journal article at the moment, ostensibly in order to make my viva easier when I’ve finished my Ed.D. thesis. It’s easier to prove an ‘original contribution to knowledge’ when some of it has been published in a peer-reviewed journal! You’ll understand, therefore, why this post, which constitutes the first part of the article, is Copyright (All Rights Reserved).

All human communication is predicated upon vocabularies. These can be physical in the form of sign language but, more usually, are oral in nature. Languages, therefore, are codified ways in which a community communicates. However, such languages are not static but evolve over time to meet both changing environmental needs and to explain and deal with the mediation and interaction provided by tools.

As Wittgenstein argued, a private language is impossible as the very purpose of it is communication with others. Those with whom one is communicating must have the ‘key to open the ‘box’. Yet if all language is essentially public in nature it begs the question as to how popular terms can be used in such a variety and multiplicity of ways. Terms, phrases and ways of speaking have overlapping lifecycles used by various communities at particular times. A way of describing a concept often enters a community as a new and exciting way of looking at a problem, perhaps as a meme. Meanwhile, or soon after, the same concept might be rejected by another community as out of date, as ‘clunky’ and lacking descriptive power.

Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions provides some insight into this process. Kuhn identified periods of ‘normal’ science in a given field which would be followed by periods of ‘revolutionary’ science. The idea is that a community works within a particular paradigm (‘normal’ science) until the anomalies it generates lead to a crisis. A period of ‘revolutionary’ science follows in which competing paradigms that can better explain the phenomena are then explored. Some are accepted and some are rejected. Once a paradigm gains general acceptance then a new period of ‘normal’ science can begin and the whole process is repeated. Kuhn’s theory works in science because there are hard-and-fast phenomena to be explored; theories and concepts can be proved or disproved according to Popper’s falsifiability criterion.

The same is not necessarily true in the social sciences, however: it can be unclear what would constitute a falsification of certain widely-held concepts and theories. Indeed it is often the case that they gain or lose traction by the status of the people advocating them rather than the applicability and ‘fit’ of the concept. In addition, a concept or theory may serve a purpose at an initial particular point in time but this utility may diminish over time. Unfortunately, it is during this period of diminishing explanatory power that terms are often evangelised and defined more narrowly. This should lead to a period of ‘revolutionary’ social science but this is not necessarily always the case. If, for example, a late-adopting group holds political power or controls funding streams, even those in groups who have rejected the concept may continue to use it.

An example of this process would be the coining of the terms ‘digital natives’ and ‘digital immigrants’ in 2001 by Marc Prensky. This led to a great deal of discussion, both online and offline, in technology circles, education establishments and the media. Debates began about the maximum age of a ‘digital native’, what kind of skills a ‘digital native’ possessed, and even whether the term ‘digital immigrant’ was derogatory. As the term gained currency and was fed into wider and wider community circles, the term became more narrowly defined. A ‘digital native’ was said to be a person born after 1980, someone who was ‘digitally literate’, and who wouldn’t even think of of prefixing the word ‘digital’ to the word ‘camera’.

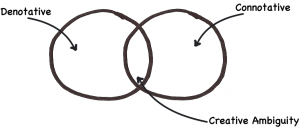

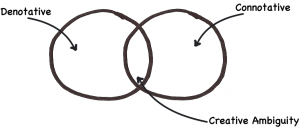

It is our belief that the explanatory power of a concept, theory or term in the social science comes, at least in part, through its ‘creative ambiguity’. This is the ability of the term – for example, ‘digital native’ – to express a nebulous concept or theory as a kind of shorthand. The amount of ambiguity is in tension with the explanatory power of the term, with the resulting creative space reducing in size as the term is more narrowly defined. Creative spaces can also bring people together from various disciplines, allowing them to use a common term to discuss a concept from various angles.

The literal meaning of a term is the denotative element and includes surface definitions of a term. For ‘digital literacy’ this would be to simply equate the term with literacy in a digital space. The implied meaning, on the other hand, is the connotative element and deals with the implied meaning of a term. With digital literacy this would involve thoughts and discussion around what literacy and digitality have in common and where they diverge. The creative space is the ambiguous overlap between the denotative and connotative elements:

Such creative ambiguities are valuable as, instead of endless dry academic definitions, they allow for discussion and reflection, often leading to changes in practice. In order to maximise the likelihood and impact of a creative space it is important that a term not be too narrowly defined, for what it gains in ‘clarity’ it loses in ‘creative ambiguity’. There is a balance to be struck.

Terms and phrases, however, can be ambiguous in a number of ways. Some of these types of ambiguity allow for creative spaces between the denotative and connotative elements of a new term to a greater or lesser degree. In other words, they involve greater or smaller amounts of ambiguity.

References

Prensky, M. (2001) Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants (On The Horizon, 9(5), available online at http://dajb.eu/fpIs05, accessed 14 December 2010)

The rest of the journal article deals with Empson’s 7 types of ambiguity as related to the above. You may want to check out the posts I’ve written previously relating to creative ambiguity. I’d welcome your comments!