TB871: The ‘eternal triangle’ of systemic triangulation in CSH

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) is a systems thinking approach that contrasts ‘systems’ vs ‘reality’ and provides 12 boundary questions to help build a reference system. In this post, I’m going to discuss the ‘systemic triangulation’ involved in creating a reference system.

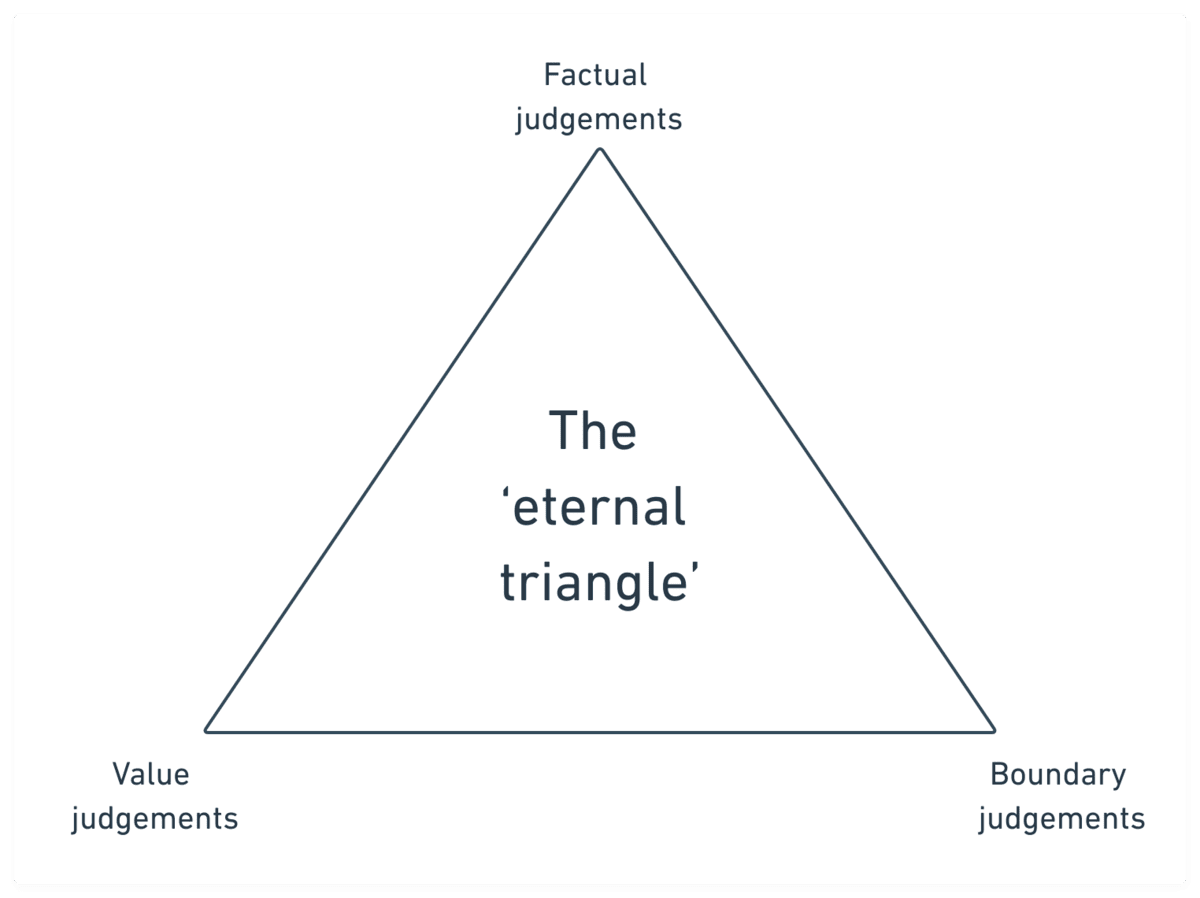

We have thus three sets of judgements that condition the ways we conceive of situations and systems: factual judgements, value judgements and boundary judgements. Judgements of fact and judgements of value are often said to be interdependent, but it usually remains unclear what exactly that means and how it is to be explained. CSH gives us a precise explanation: ‘facts’ and ‘values’ depend on one another as both are conditioned by the same boundary judgements. For example, when we expand our boundary judgements regarding what belongs to the relevant situation (say, when we recognise a previously ignored condition of success), previously ignored facts may become relevant; but in the light of new facts, our value judgements may suddenly look different and need revision. Similarly, when our value judgements change, we will need to revise our boundary judgements accordingly, and in consequence new or different facts become relevant.

CSH refers to this triadic interplay of reference system, relevant facts and values as an eternal triangle that we need to think through, and to its methodological employment for critical purposes as systemic triangulation (Ulrich 2000, p. 251f; 2003, p. 334; 2005, p. 6; and 2017).

(Reynolds & Ulrich, 2020, p.296)

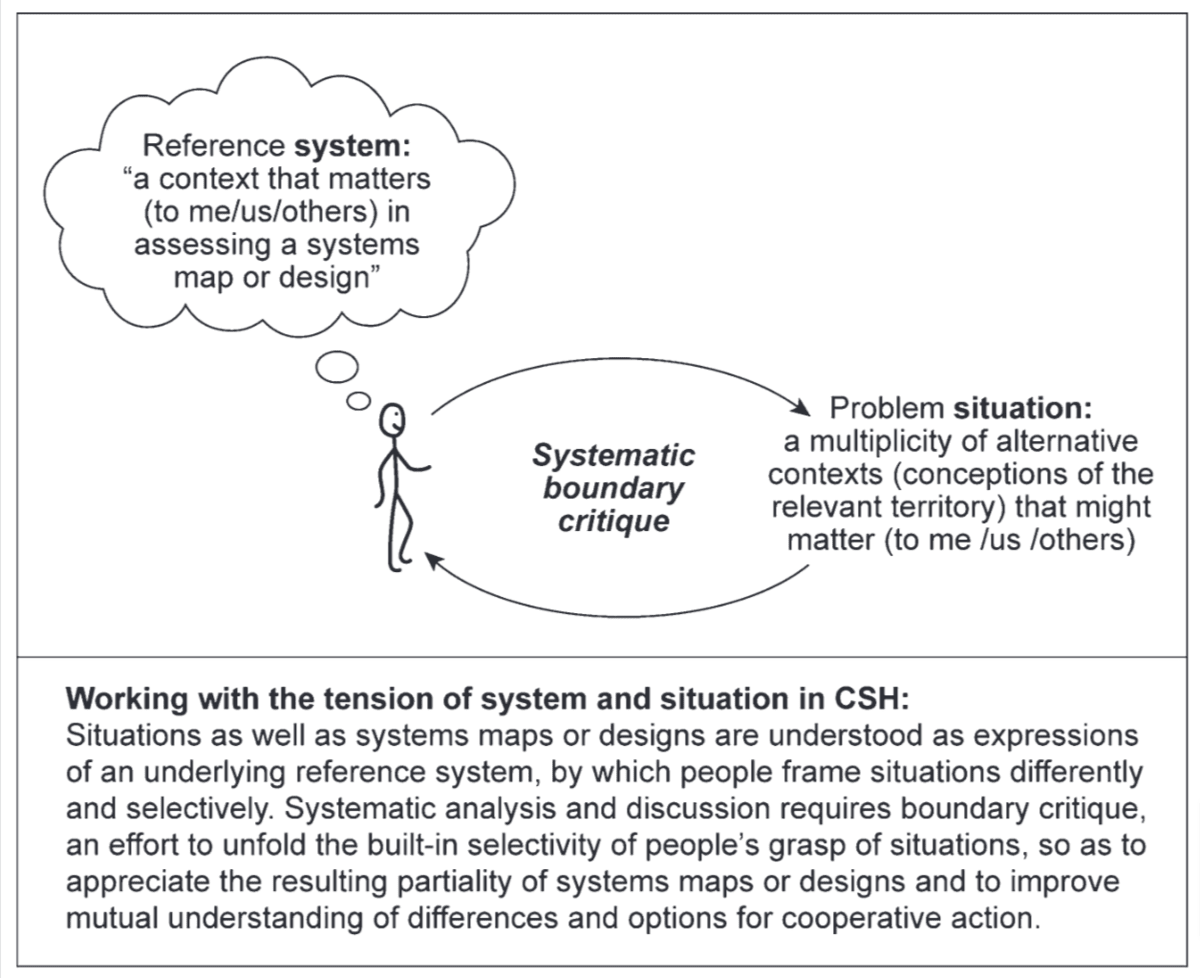

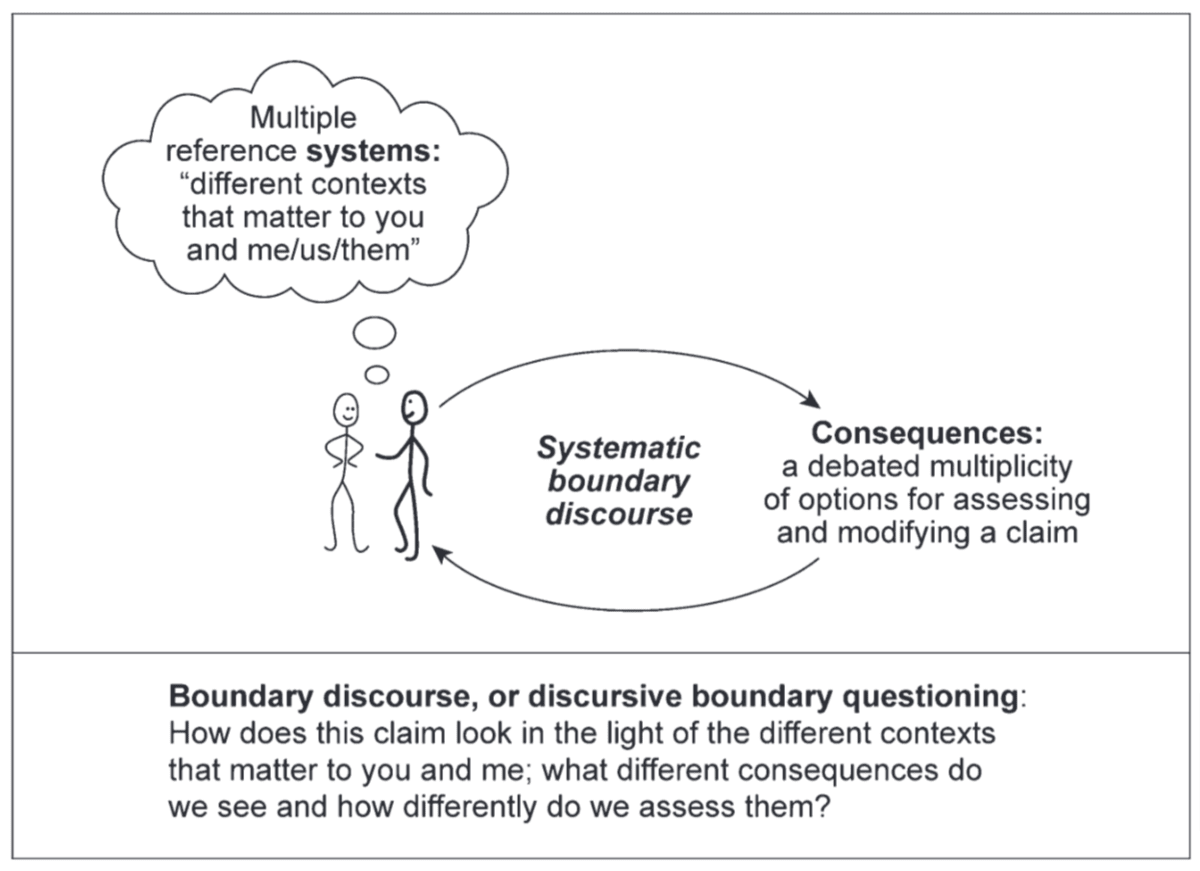

The idea with systemic triangulation is to gain a deeper understanding of the selectivity of various claims within a reference system. It’s a form of ‘stepping back’ from one’s reference system to appreciate other perspectives. Ulrich and Reynolds suggest that this ushers in what they call a “new ethos of professional responsibility” for systems practice, measuring claims “not by the impossible avoidance of justification deficits but by the degree to which we deal with such deficits in a transparent, self-critical and self-limiting way” (Ibid., pp.297-8).

Example: Curriculum development

Consider the process of developing a national educational curriculum. Those responsible for the curriculum may initially focus on achieving high academic standards and promoting social unity. Their decisions are guided by value judgements, such as academic excellence and the creation of a cohesive society.

The factual judgments made during this process are informed by research on educational outcomes and the effectiveness of various teaching methods. These ‘facts’ are not objective but are interpreted in the light of the developers’ values.

Boundary judgments also play an important role here. Initially, the curriculum might only consider its direct impact on students, such as improving test scores. However, if the scope is broadened to include wider societal impacts, such as cultural inclusivity and relevance, the picture changes. New facts then come to light, like the need to represent diverse cultural perspectives within the curriculum. This shift in boundaries can lead to significant revisions in both the content of the curriculum and the way it is delivered.

This example illustrates how changes in boundary judgments can alter the facts and values considered, ultimately shaping the outcomes of the curriculum development process.

What I, personally, like about CSH is that it clearly demonstrates the importance of context. For example, the ‘eternal triangle’ shows that the maps, diagrams, and other things we produce as a result of systems thinking, cannot be better than the understanding we have the context of a situation. We can be the most experienced and credentialed person in the world, but without that understanding, without being open and honest with ourselves and others about our assumptions and biases, we’re unlikely to be of help. As Ulrich and Reynolds put it, this encourages what they call “methodological modesty” (Ibid., p.299).

References

- Reynolds, M. and Ulrich, W. (2020) ‘Critical Systems Heuristics: The Idea and Practice of Boundary Critique’ in Reynolds, M. and Holwell, S. (eds.) Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide, 2nd edn, London: Springer-Verlag, pp. 255-300.