TB871: Lateral Thinking, Transitional Objects, and Metaphors

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

On the desk of my home office I have a set of Brian Eno’s ‘Oblique Strategies‘ cards. Every so often, I’ll pull out a card at random as a prompt to generate a creative solution to a knotty problem. Each card provides a unique prompt which is designed to shift your perspective and inspire new ways of thinking, for example, “Accretion” or “Who should be doing this job? How would they do it?”.

Although I didn’t know it a decade ago when I bought the cards, this technique aligns well with the principles of systems thinking and the use of ‘transitional objects,’ offering a pathway to explore complex situations in innovative ways.

Transitional objects

In systems thinking, the concept of ‘rich pictures’ is used to capture and express the complexity of perceptions within a particular situation. I used this approach in my previous MSc module, TB872. These pictures provide a creative outlet for individuals to project their understanding and emotions about a scenario, encompassing both positive and negative aspects.

This method is an example of using ‘transitional objects,’ a concept introduced by the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. These objects, which exist simultaneously in the realms of reality and imagination, serve as tools for individuals to navigate the boundaries between fantasy and fact, internal and external realities, and creativity and perception (Winnicott, 1971).

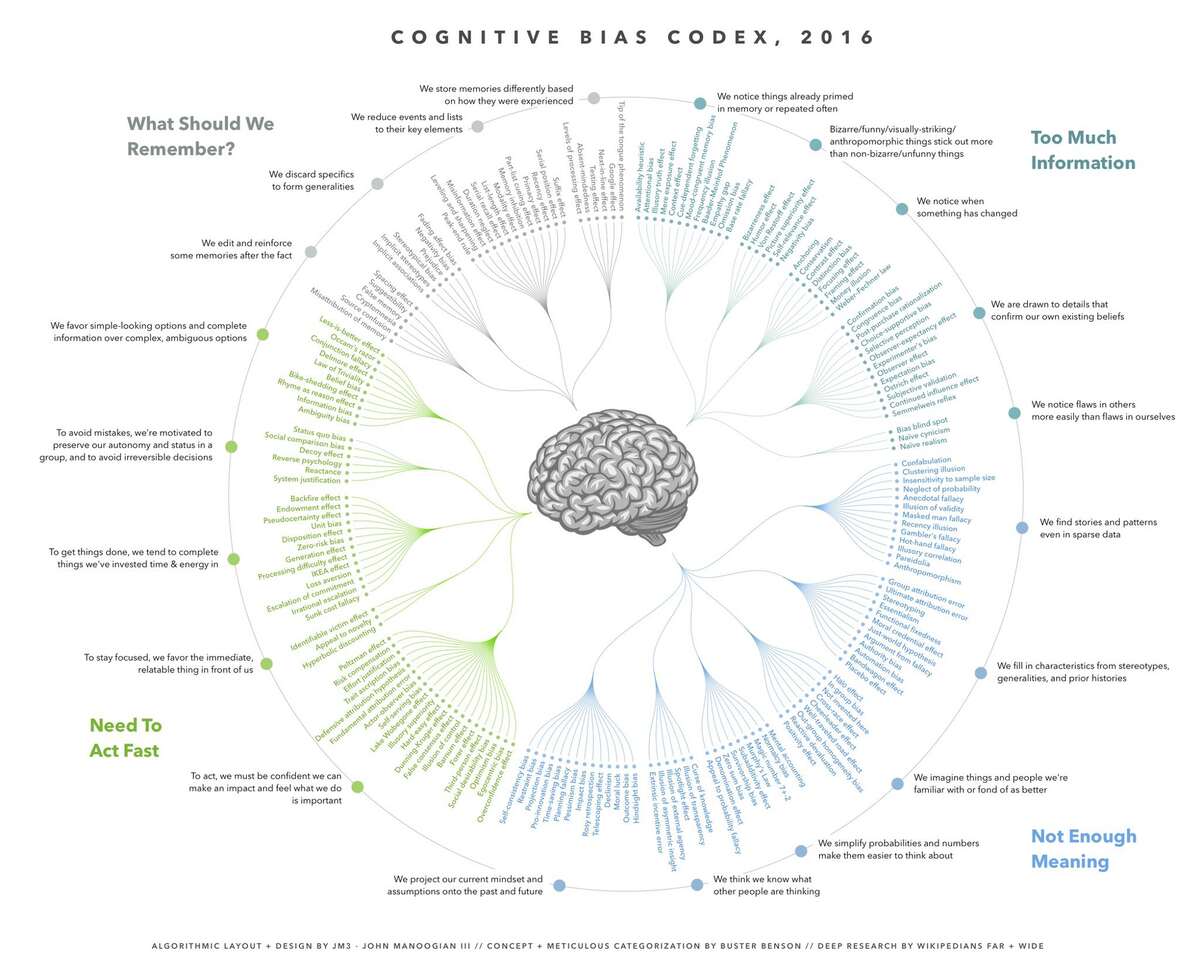

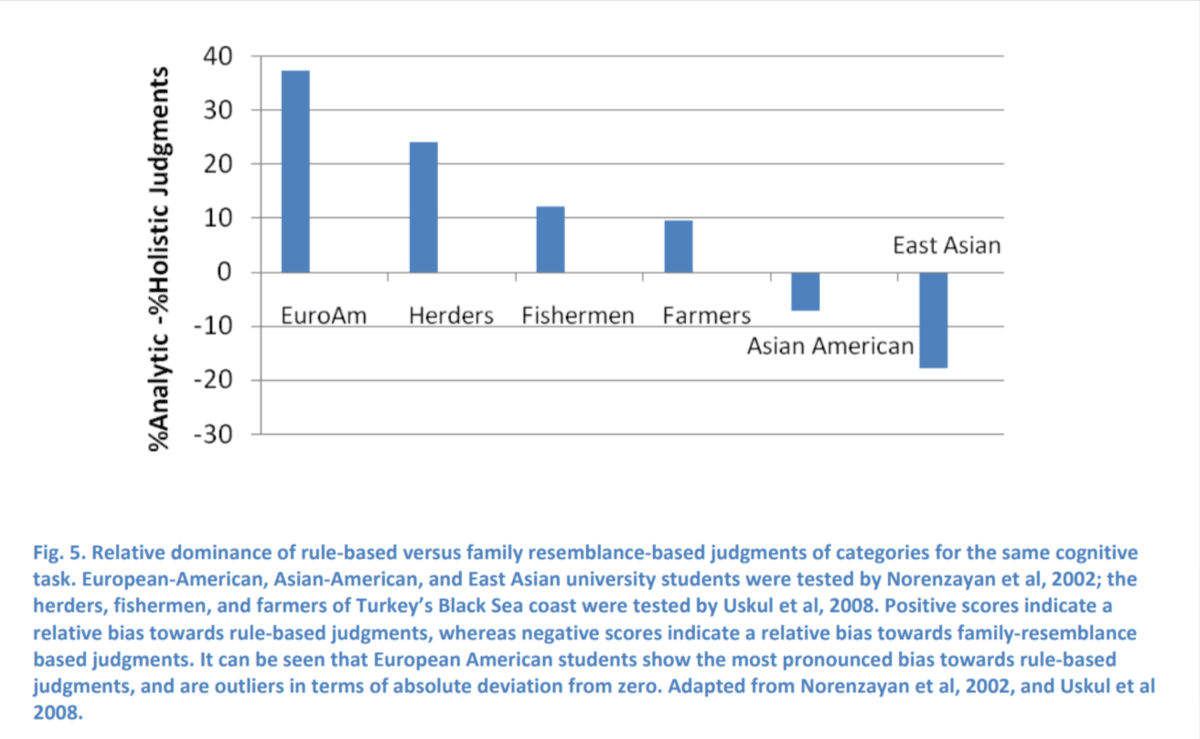

In the context of systems thinking, rich pictures function as transitional objects by enabling participants to externalise and communicate their internal thoughts and feelings about a situation. This process of externalisation is important for understanding and addressing the nuances inherent in any system. As I explored in a recent post, situations are fundamentally ambiguous, and we are all subject to cognitive biases.

The use of rich pictures and other transitional objects in systems thinking can provide several benefits:

- Creative expression: represent perceptions and emotions creatively can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the situation.

- Intricacy management: visually mapping out the various elements and their interconnections can help show and manage the intricacies of systems.

- Enhanced communication: a visual approach can serve as a ‘common language’ to help facilitate communication among stakeholders with diverse perspectives.

- Emotional engagement: the process of creating and discussing transitional objects can engage participants emotionally, leading to deeper involvement and commitment.

- Problem identification: transitional objects can help identify underlying problems and issues that may not be immediately obvious.

Lateral thinking

Edward de Bono‘s concept of lateral thinking complements the use of transitional objects in systems thinking. De Bono emphasised the importance of encouraging the brain to break free from familiar patterns to produce creative and novel solutions. He likened this process to the way humour works, where a sudden shift in perspective leads to a new understanding. I’ve used his six thinking hats successfully with students, for example, to help them think through situations from different points of view.

Lateral thinking involves provocation and the use of unusual scenarios to stimulate new ways of thinking. In his Atlas of Management Thinking, de Bono illustrated this with a block improbably balanced on one corner, which symbolises the unexpected and the need to think differently about familiar objects. By integrating lateral thinking techniques, systems thinking practitioners can further enhance their ability to explore intricate situations.

As illustrated in the image, provocation is a key process in lateral thinking. It involves deliberately creating an unstable idea or situation to break away from conventional patterns of thought. This method encourages looking at the ‘what if…’ and ‘suppose…’ scenarios, thus encouraging a shift in perspective that can lead to innovative solutions.

Using metaphors

I’m a big fan of using metaphors in both my professional and personal life. I find that they help ‘unlock’ thinking that would otherwise not be available to me. So, when thinking about my area of practice and system of interest (“a system to promote lifelong learning” in a library context) I could think about the library as metaphorically being a ‘laboratory,’ a ‘seed vault,’ or a ‘constellation map.’

If we go a bit further with the latter of these, then a library can be viewed as a map of the night sky, where each book or resource is a star that helps navigate the vast expanse of human knowledge. Connecting these stars forms constellations, representing interconnected ideas and concepts. Just as navigators have historically used constellations to find their way, learners may use the library to chart their course through the ‘sea’ of information. This metaphor emphasises the interconnectedness of knowledge and the guidance that a library provides if we consider lifelong learning a ‘journey.’

References

- The Open University (2020) ‘Lateral thinking’, TB871 Block 3 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261488§ion=4.7.1 (Accessed 12 July 2024).

- Winnicott, D.W. (1971) Playing and reality. New York: Tavistock Publications.